Take a close look: animals are everywhere in prosthetic limb development.

The 2011 film Dolphin Tale is based on the true story of Winter, a bottlenose dolphin who lost her tail after it was injured in a crab trap. Winter was rescued off the coast of Florida and brought to the Clearwater Marine Aquarium (CMA) for medical attention in 2005. Shortly after her arrival at the CMA, Dr. Kevin Carroll, Vice President of the Hanger Clinic, an American prosthetics and orthotics manufacturer, heard her story on the radio. “My heart went out to her,” Dr. Carroll recalled, “and I thought I could probably just put a tail on her.”[1]

At the time, no one had constructed a prosthetic tail for a dolphin, and creating an artificial limb exclusively for underwater use presented many challenges. The correct prosthetic liner would be especially important. It had to adhere to Winter’s delicate skin, hold tight in water, and stay in place when the 400 pound dolphin thrust her tail to swim.[2] Dr. Carroll and his colleague, Dan Strzempka, a Hanger Clinic prosthetist and an amputee, collaborated with a chemical engineer to develop a new material for Winter’s prosthetic. The team invented WintersGel, a thermoplastic elastomer similar to silicone, but much softer. It was fashioned into a sock that rolled onto the dolphin’s tail stump.

Next, Carroll and Strzempka created an artificial tail. “Little did I know it was going to take a year and a half.” Carroll explained: “with a person, we have one long, solid bone. With a dolphin, [the prosthetic] needs to move along with her full spine.”[3] While she swam, Winter’s team used a motion-tracking, laser-imaging device at the Hanger Clinic to create a three-dimensional model of the Dolphin’s body and tail stump. With this model, they extrapolated a replacement tail fluke. This crafted rubber tail was sturdy enough to hold its shape when pulled through the water, but flexible enough to move with Winter’s spine. Winter is now 14 years old and fully acclimated to her prosthetic tail.

Winter’s story is not just the heart-warming stuff of family movies. The technology that Carroll and Strzempka developed for Winter is now helping human patients. WintersGel is softer than other liners, and it distributes pressure and weight more evenly. This eliminates painful “hot spots,” or areas of friction where the prosthetic puts pressure on the body. Because of these unique properties, WintersGel is especially beneficial for athletes with limb amputations. Prosthetic liners made of WintersGel, distribute impacts better than other liner materials and hold onto the wearers’ skin even if they sweat.[4] WintersGel also helps patients with skin sensitivity. Carroll used WintersGel on a 9-year-old girl who lost both of her legs after being burned in an accident. Previously, the patient could not tolerate traditional prosthetic liners because they were painful against her scar tissue. Carroll fitted the young girl with WintersGel sleeves and says that now “she’s flying around,” on her prosthetic legs.[5] Though this story is not the norm, WintersGel is not the only prosthetic innovation pioneered in the animal kingdom.

OI Integrated Limbs

Osseointegrated prosthetics were used in animals first. Osseointegration (OI), invented by Per-Ingvar Branemark in 1952, is a surgical procedure in which a titanium implant is inserted into living bone. The implant serves as a permanent anchor point for a prosthetic.[6] Brånemark inserted titanium rods into the femur bones of rabbits and discovered that the bone slowly bonded to the implant’s surface. Brånemark sold his discovery to the dental industry where OI remains the foundation of modern dental implantology. Now the technique is used on an experimental basis to replace limbs in animals and humans. Authors of a 2017 article in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery estimate that 100 European amputees have successfully received OI implants. OI is still a novel approach in the United States, but animal patients are blazing a trail. [7]

Source: Open Artsor/Science Museum Group.

Source: Public Domain/Pexels

Zeus, a famous Siberian Husky OI implant recipient from North Carolina, lost his front limb in a dog attack. In 2011, it became the fifth animal to receive an OI-integrated limb at NC State University College of Veterinary Medicine. Dr. Marcellin-Little, the veterinarian who performed Zeus’ operation, recognizes the importance of OI in human medicine: “As we gain more experience with the surgical technique and the design of the limbs, we see the possible benefits for humans—implants that allow the prosthetic limbs to attach without chafing or irritation, and limbs with more natural ranges of motion.” [8] One problem that stalls OI limb use in human patients is the risk of infection at the stoma – the site where the implant exits the limb.

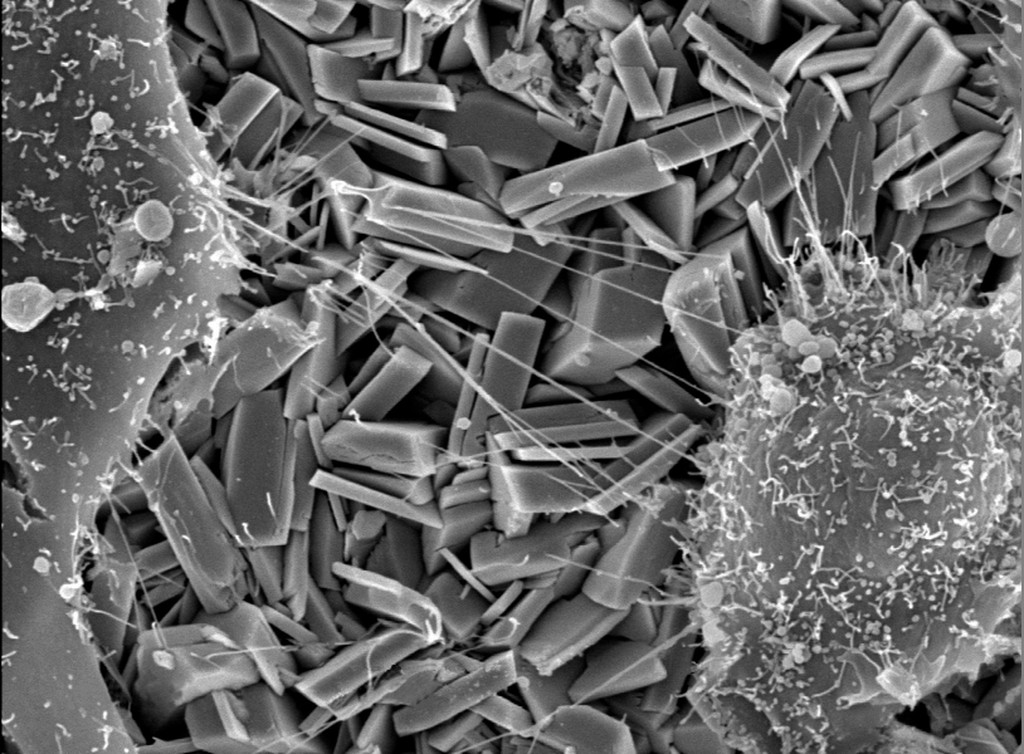

A cat has helped prosthetists solve that problem too. Oscar, “the Bionic Cat,” lost his hind legs in a combine harvester accident in 2009. His new feet are implants called Intraosseous Transcutaneous Amputation Prosthetics (ITAP). Oscar’s bioengineered ITAPs were developed by a team at University College London. These ITAPs differ from previous OI implants as they mimic the way deer antler bone grows through the skin.[9] ITAPs have a micro-honeycomb structure that allows the patients’ skin to bond to the prosthetic. The unique engineering of ITAPs reduce the risk of stoma infections associated with OI-type limbs.

One of the first Americans to receive an osseointegrated/ITAP prosthetic is retired police officer Christopher Rowles. Rowles received his prosthetic in 2017 at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. He praised his new limb in his statement: “Everything’s different. I can do things I wasn’t secure with. Even driving’s easier, even though it is my left leg that is amputated. I walk straighter, much more upright, I’m not leaning or doing anything in my gait. My body feels better.”[10]

Experimental Limbs

In the United States, OI and ITAP prosthetics are still considered experimental, not covered by most insurance providers.[11] Were they not experimental, American amputees interested in OI and ITAP limb replacements must still undergo a surgical implantation procedure followed by a lengthy recovery period, then physical rehabilitation. Many amputees, however, may be prevented from adopting OI/ITAP prosthetics due to the overbearing financial and physical considerations. Despite the potential setbacks, amputees like officer Christopher Rowles, demonstrate that OI/ITAP prosthetics not only improve quality of life, but are more feasible now.

Human prosthetists, as has been the trend since the mid-twentieth century, will likely continue to look to animals like Oscar, Zeus, and Winter for inspired solutions to human mobility. The animal kingdom has proven a fruitful place for doctors to think creatively about prosthetic devices. Although American veterinary medicine is regulated at the state level, it is not as regulated as human medicine.[12] For example, only a few states have any HIPAA-type equivalent regulation for animal records. Less strict regulations allow doctors to share information more readily, innovate, and push the boundaries of prosthetic medicine.

The unique cases of the animal amputees discussed here have benefited humans and animals alike. As the world of human prosthetic development becomes more enmeshed in animal medicine, however, we must consider the ethical and social implications of relying on animals to improve human mobility outcomes. In addition to animal amputees, animals are the inspiration and unwilling test subjects for prosthetics. Designer and researcher Kaylene Kau’s octopus-inspired tentacle arm replacement is hailed by Nerdist as “the future” of prosthetics for its exceptional functionality.[13] A deer’s antler inspired ITAP technology, cheetahs’ legs are the basis for the flex-foot runner’s prosthetic, and Brånemark’s rabbits were the test subjects that lead to the discovery of OI technology. These animals also help improve mobility outcomes for disabled humans by allowing prosthetists and scientists to imagine mobility options and solutions for human bodies. So, let’s give our animal friends some recognition for their inspiration, help, and sacrifice. Without the animal kingdom, mobility, and functionality might look different for many amputees.

–Kristen Semento is a Unidel Distinguished Doctoral Fellow studying the History of American Civilization at the University of Delaware’s Department of History. She specializes in material histories of medicine and the body in America and can be reached at semento@udel.edu.

Notes

[1] “Empowered Stories,” Hanger Clinic, accessed May 18, 2019.

[2] Ibid

[3] “Winter the Dolphin Gets Bionic Tail,” The Telegraph (May 4, 2008).

[4] Emily Anthes, “Animal Prosthetics Help Human Amputees Move Again,” Wired (September 27, 2011).

[5] Ellen McCarthy, “Movies: True Story behind ‘Dolphin Tale’,” The Washington Post (September 23, 2011).

[6] “What Is Osseointegration,” Amputee Osseointegration Foundation Europe, accessed May 19, 2019.

[7] Jacqueline S. Herbert, Mayank Rehani, and Roobert Stiegelmar, “Osseointegration for Lower-Limb Amputation: A Systematic Review of Clinical Outcomes: JBJS Reviews,” The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, October 2017.

[8] “Pioneering Implant Surgery Aids Zeus and Prosthetic Limb Design,” NC State Veterinary Medicine, April 3, 2011.

[9] “Bionic Feet for Amputee Cat,” BBC News (June 25, 2010)

[10] Joseph Frankel, “Bone Implants and Prosthetics,” Healthline (March 15, 2018).

[11] Veterans Administration, “Osseointegration (OI) For Direct Skeletal Attachment of Prosthetic Limbs in Beneficiaries with Amputations” United States Department of Defense (2017).

[12] “State Regulation of Veterinary Facilities,” American Veterinary Medical Association, October 2019.

[13] Matthew Hart, “Prosthetic Tentacle Appendages Are the Future,” Nerdist, August 3, 2017.