At first sight it seems that prelingually deaf people (known by their contemporaries as “deaf and dumb”) were condemned to exclusion and marginalisation in Renaissance Europe. In seventeenth-century England, a lawyer put it like this: prelingually deaf people were “looked upon as misprisons in nature, and wanting speech, are reckoned little better than dumb animals.” As Elizabeth Bearden has written in her magnificent study, Monstrous Kinds, “linguistic capacity was a benchmark for personhood” in much of Western Europe.1

My research into deafness in Renaissance England, however, suggests a more nuanced approach to speech and deafness than is often portrayed in contemporary legal and literary sources. There was a legal tradition across Renaissance Europe that since prelingually deaf people could neither hear nor speak, they could not understand the world around them and therefore should legally be treated as “infants.” This meant they could not make wills, get married, or be held responsible in a court of law. Despite these restrictions, however, the reality was very different in Tudor and Stuart England: prelingually deaf men and women married, made wills, inherited property, raised families, and held down jobs. Often, they were so integrated into their local communities, that their deafness or hearing loss was rarely—if ever—mentioned. Instead, these men, women, their families, and friends—both hearing and deaf—communicated using manual signs, which were considered a legal, and eloquent, form of speech.

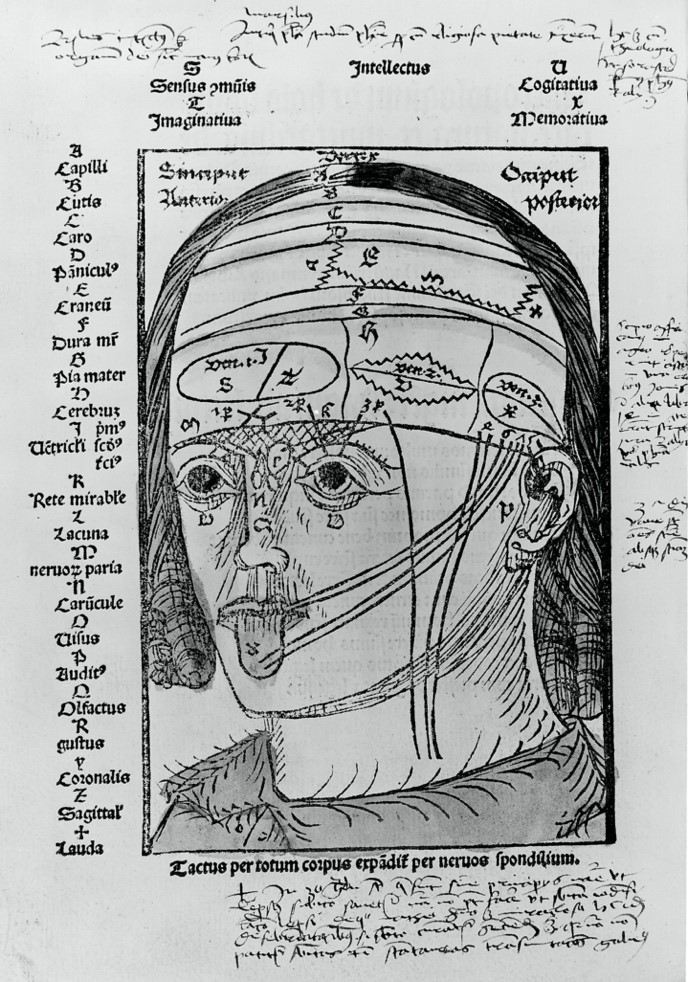

In the Renaissance, prelingually deaf people—known by contemporaries as “deaf and dumb”—were often portrayed as legally incapable, drawing on medical and anatomical texts. It was a long-held belief, stretching back to Ancient Greece: Aristotle for example, argued that since hearing was the chief sense of learning, deaf people were less clever than blind people. Other Renaissance authors argued that speech was a prerequisite for abstract thought. They argued that deaf people could not understand the world around them and therefore they could not be held responsible for their actions (much like an infant or someone deemed “insane”). In a handbook for magistrates from the seventeenth century, legal scholar Michael Dalton advised magistrates that if “a man born deaf and dumb killeth another, that is no felony, for he cannot know whether he did evil or no.”2 This reasoning thus had repercussions for deaf people: prelingually deaf people were ostensibly barred from marriage (they could not express consent vocally) and from receiving sacraments in Church (they could not express their understanding of the faith in speech). Since it was believed that deaf people could not understand or express understanding, they were also prevented from making wills.

The reality for many prelingually deaf people, however, was very different. The exclusionary perceptions of deafness, speech, and reason were challenged by a range of legal, medical, and theological writers. At the same time Michael Dalton was writing, an English anatomist, Helikiah Crooke, argued that “nature hath armed a Man, although he be deaf, with Reason and Understanding for Invention.”3 During this period, Protestant and Catholic ministers started to argue that deaf people were saved by God, even if they could not hear the service or sermon. As Martin Luther concluded in 1519, ”if preaching does not infuse the spirit, then he who hears, does not differ at all from one who is deaf.” And through the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, churches in England, Ireland, New England, and across Europe made accommodations to allow deaf people to take part in their services.4

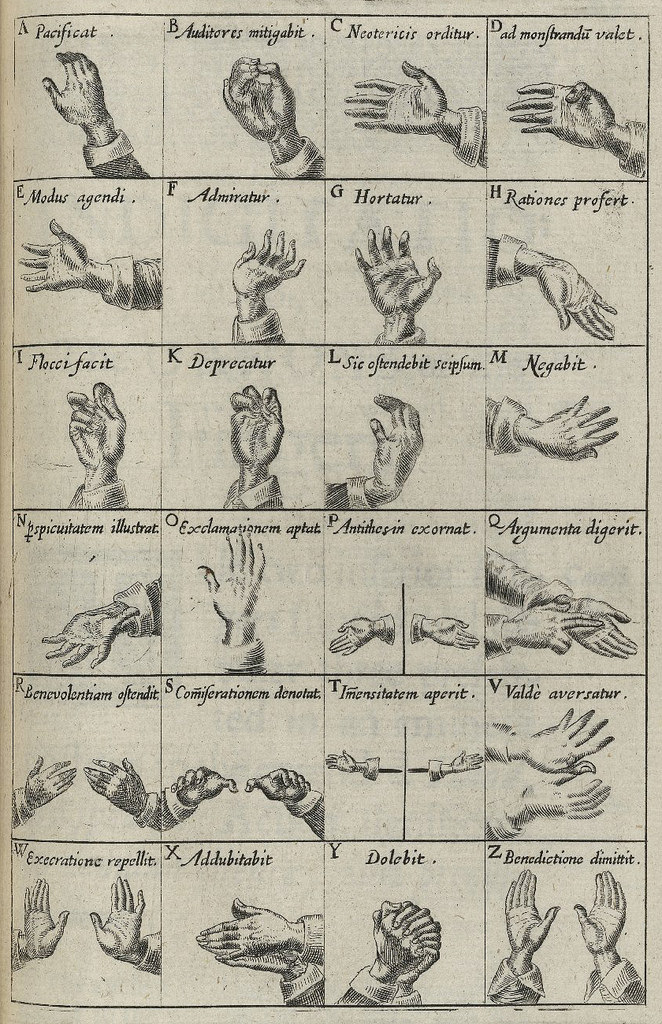

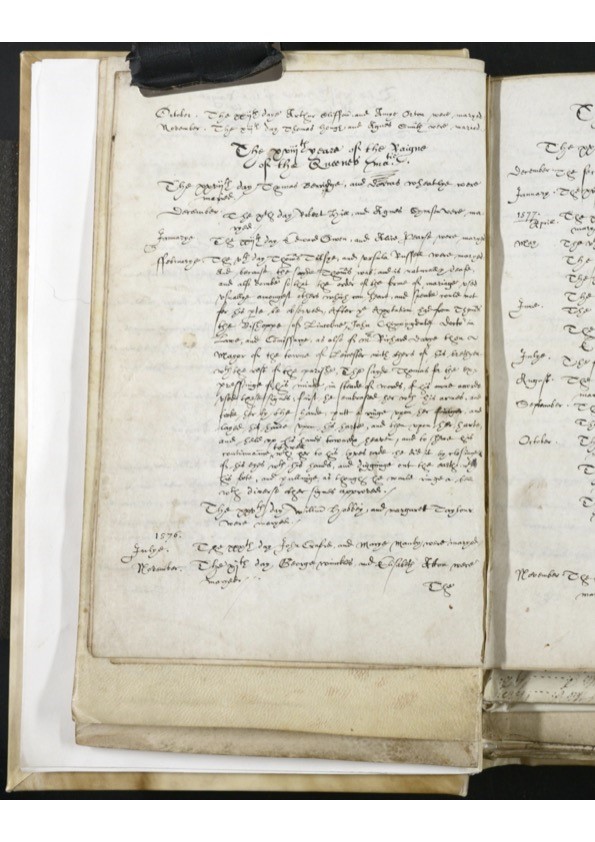

This recognition was achieved when contemporaries realized that deaf people could express themselves, thereby demonstrating their understanding of the world. Sometimes this was through vocal speech, but increasingly it was through the use of manual signs. In sixteenth-century England, Protestant preachers argued that sign languages were more eloquent than vocal speech, allowing people to express divine mysteries that could not be captured in mere words. Perhaps, therefore, it is unsurprising that it was the Church of England that was at the forefront of the legal recognition of manual signs as a valid form of speech. Marriage ceremonies were a place where the spiritual and secular collided: it was a legal contract and in pre-civil war England almost all marriages took place in the Church of England. The most well-known sign language marriage took place in Elizabethan Leicester. The local bishop, the bishop’s legal advisor, and Leicester’s mayor were asked to judge whether the prelingually deaf man, Thomas Tilsey, could legally consent to get married. Following a consultation with Tilsey’s neighbors and local parishioners, it was agreed that Tilsey could marry Ursula Russel using a form of sign language which was recorded at length by the churchwardens. They wrote that

“for expressing of his mind, instead of words, of his own accord, [Thomas] used these signs :first he embraced her [Ursula] with his arms, and took her by the hand, put a ring upon her finger and laid his hand upon his heart and then upon her heart, and held up his hands towards heaven, and to show his continuance to dwell with her to his life’s end, he did it by closing of his eyes with his hands and digging out the earth with his foot, and pulling as though he would ring a bell, with diverse other signs approved,”5

And although Thomas Tilsey’s marriage was unusual, it was not unique.

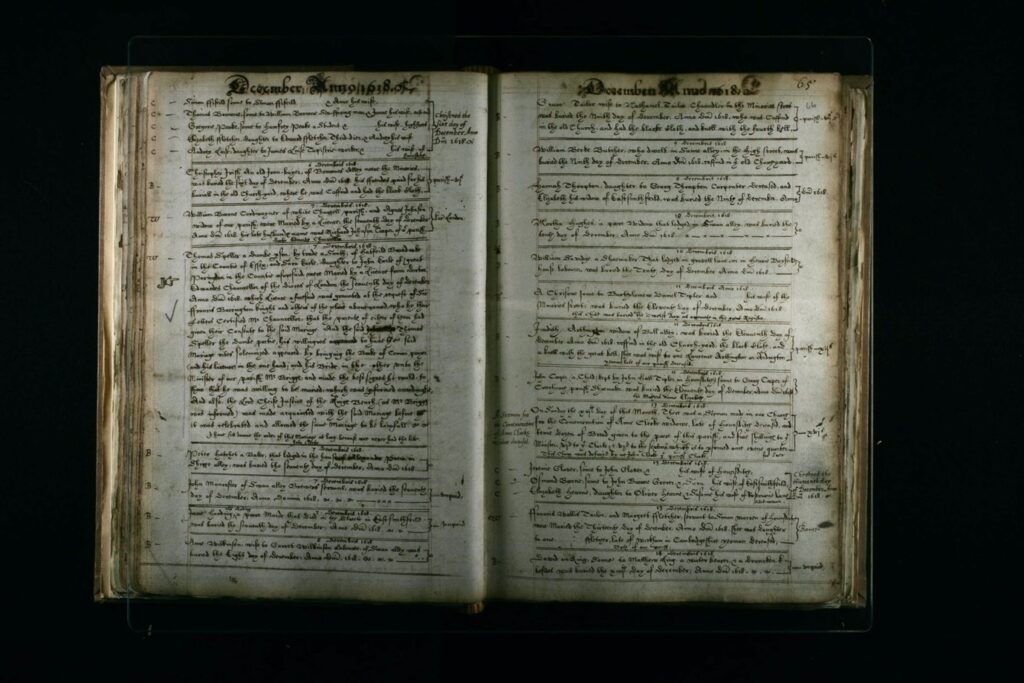

Throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, deaf men and women got married in the Church of England. Often, though not always, they were granted special licenses by the local bishop. In 1618, a deaf man Thomas Speller married Sara Earl in central London, with the churchwardens noting that “we never had the like before.” In 1631, another prelingually deaf man, George Blunt of Bridgewater in Somerset, was granted a license to marry a widow, Christobel Cox. A few years later, two prelingually deaf brothers, Edward and William Gostwick, married, with Edward marrying Mary Lytton, a “Lady of a great and prudent family.”6

All of these marriages took place using manual signs, reflecting a growing belief that sign language was a legitimate (and eloquent) form of communication. By 1624—only a few years after Michael Dalton told JPs that prelingually deaf people were to be treated like infants—manual signs were accepted as a legally-valid form of speech. The leading Church of England lawyer, Henry Swinburne advised clergy that “that which cannot be expressed in words may be declared in signs,” and therefore, “they which be dumb and cannot speak, may lawfully contract matrimony by signs, which marriage is lawful, and availeth not only before God, but before the Church.7 By allowing prelingually deaf people to use sign language in formal situations, clerics promoted the belief that deaf people were capable of rational thought. And, as it became clear that vocal speech was not a prerequisite for rational thought, contemporaries realised that prelingually deaf people had the same rights and needs as hearing people. Deaf marriages were, therefore, an important step on the path to integration for deaf men and women.

This is not to suggest that the Renaissance period was a golden age for deaf men and women. But, this research suggests we should adopt a more nuanced reading of the literary and legal texts promoting the complete exclusion of prelingually deaf people. Instead, as my work shows, those same people were part of their communities, often using their natural language, sign, to express their beliefs, hopes and fears and to assert their legal and spiritual personhood.

Dr. Rosamund Oates is a Reader/Associate Professor in Early Modern History at Manchester Metropolitan University, U.K. Her expertise is in early modern culture, and she has recently been awarded a Leverhulme Fellowship to work on the project, “Silent Histories: Deafness and Hearing Loss in Early Modern England.” She leads an interdisciplinary research cluster, “Cultures of Disability.” Recent publications include: “Speaking in Hands: Early Modern Preaching and Signed Languages for the Deaf,” Past and Present (2022), ed. with J. Purdy, Communities of Print: Readers and Their Books in Early Modern Europe (Brill, 2022); and Moderate Radical: Tobie Matthew and the English Reformation (Oxford, 2018). Dr. Oates is on Twitter as @drrosamundoates.

Header Source: John Bulwer, Chirologia (1644). © Folger Shakespeare Library (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Notes

- Bulwer’s italics. John Bulwer, Philocophus: or the Deafe And Dumbe Mans Friend (London, 1648), 102, 109. Elizabeth B. Bearden, Monstrous Kinds: Body, Space and Narratives in Renaissance Representations of Disability (Ann Arbor, 2019), 91-2.

- Michael Dalton, The Countrey Justice (London, 1618, STC 6205) 215–16.

- Helkiah Crooke, Mikrokosmographia : A Description of the Body of Man (London, 1615), 700-701.

- Commentary on Galatians 3:2: Martin Luther’s Lectures on Galatians’, trans R. Jungkuntz in Luther’s Works: American Edition xxvii, repr. in Brock and Swinton, Disability in the Christian Tradition, 205-6.

- Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland, Parish Register of St Martin’s Leicester, DE 1564/5.

- London Metropolitan Archives, Parish Register of St Botolph’s, Aldgate, 1558-1625, p. 87. Rosamund Oates, ‘Speaking In Hands: Early Modern Preaching and Signed Languages for the Deaf’, Past and Present (2022), forthcoming.

- Henry Swinburne, A Treatise of Spousals or Matrimonial Contracts (London, 1686) 203-4.