During my sabbatical in the spring of 2019, I visited the Hayward Gallery in London. At that time, they were hosting Kader Attia’s exhibit “The Museum of Emotion.” I was drawn to this particular exhibit because of its dual description of engaging with how Western cultures continue to view non-Western cultures through the lens of colonization and of examining the idea of “repair,” including physical and psychological injury. As I neared the end of the exhibit, my mind already full of questions and ideas, I stopped at a sculpture of interlinking sheep horns. Entitled “Schizophrenic Melancholia,” the description explained that Attia experienced a healing ceremony called “Ndeup” (Dakar, Senegal), in which the “bad energy,” or mental illness, of an individual was transferred to the horns. This ritual has a long history and highlights a community engagement with mental health that we do not tend to see in Western societies.

My encounter with this sculpture was an unexpected but a welcoming connection to a topic that I have been thinking about and researching for a while: How is medieval disability, and medieval mental disability, curated in cultural heritage spaces? My trip was partially comprised of visiting several locations in London, Germany, and Belgium with connections to medieval disability or medicine and, secondarily, as with my visit to Attia’s exhibit, visiting other spaces engaging with disability in some way. Attia’s “Schizophrenic Melancholia” provided a valuable example of representing the tangible historical heritage of mental health.

Before continuing to think about how to represent medieval mental disability, I would like to step back to talk about the representation of medieval disability in general in cultural heritage spaces. To my knowledge, with the exception of pieces of relevant exhibitions at the Wellcome Collection and a significant section of the Richard III Visitor Centre, which focuses on the discovered king’s scoliosis, there has not been an exhibition exclusively dedicated to the topic of medieval disability. In reaching out to major institutions that house medieval collections, I have received little in the way of specifics as to how their collections represent disability, although there is a general interest in figuring out ways to make these interpretations in the future.

This is not to say that there aren’t artifacts that have already been interpreted in light of disability. For instance, the Coppergate Woman at the JORVIK Viking Centre is discussed in their guidebook in terms of the potential limp revealed through pathological analysis. There are exhibits that do treat disability to a certain extent, yet these often depict the disabled in very limited ways. At the Morgan Library and Museum, “Medieval Monsters: Terrors, Aliens, Wonders” confined the disabled to the section on “Aliens,” only presenting those ways the disabled were represented as monstrous. The Getty Museum’s “Outcasts: Prejudice and Persecution in the Medieval World” included a section on “Ableism and Classism,” focusing on the role of the disabled in charity and how they were often satirized. I want to emphasize that while these are excellent exhibitions brought the culture of the Middle Ages to broader audiences and certainly no exhibit can “do it all,” they also in their way contributed to a singular idea of historical disability that does not engage with its rich and significant complexity. For all intents and purposes, medieval disability remains hidden in the artifact vaults.

Medieval mental disability, in some ways, has not even made it into the vaults. Inquiries about artifacts related to medieval physical disability tend to reveal individual pieces or potential ways in which pieces could be interpreted (shoes with unusual wear patterns, medical paraphernalia, etc.). Inquiries about artifacts related to medieval mental disability generally are met with far less response. Why? There are many reasons we could explore – not the least of which is the stigma associated with mental health – but for our purposes here we will look at one: it can be difficult to imagine how to make physical that which is often invisible.

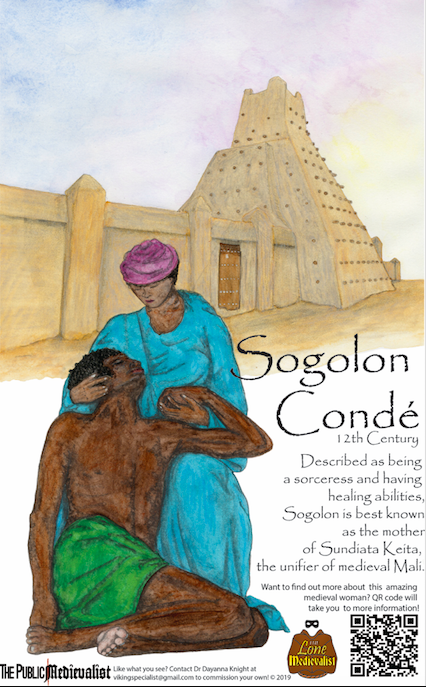

Returning to Attia’s “Schizophrenic Melancholia” can help us begin to create an exhibit centering historical and premodern mental health. Attia’s sculpture makes tangible that which might otherwise be quite abstract. Exhibitions about modern mental disability, which have been increasing in the last few years, often focus on artistic renderings created by disabled artists. A recent exhibit in the Spaulding R. Aldrich Heritage Gallery at Open Sky Community Services in Whitinsville, MA, highlighted the art of an autistic painter, “Beautiful Minds-Dyslexia and the Creative Advantage” at Science Museum Oklahoma, and “In the Mind” at Freespace Gallery in London are examples of this method of visualizing mental disability. Taking the lead from Attia, artistic representations of medieval mental disability as found in all kinds of documents from the period would be a way to meld the historical and the modern. As an example of a physical disability artistic rendering, the Women in the Middle Ages poster project sponsored by the Lone Medievalist and the Public Medievalist commissioned an artwork by Dr. Dayanna Knight to depict the characters from the medieval African text Sundiata: Sogolon Condé, described as “hunch-backed” and “ugly” to the point of disfigurement, and her son, the eventual emperor of Mali, Sundiata, born without the use of his legs. Such imagined interpretations could also be applied to mental disability and the rich amount of descriptions we have from the period.[i]

To think more in terms of interpretation of artifacts, we could consider how to represent the experience of the disabled. On one hand, we could look at this approach in terms of managing mental health. In the fourteenth-century Zibaldone da Canal by a Venetian merchant, rosemary is presented as having a number of uses, particularly for warding off nightmares and for aiding in the “weakness from rage.”[ii] Medieval depictions of rosemary and other herbals with similar descriptions could be examined from this perspective. Another approach could be in terms of the physical skull and brain. We have numerous illustrations of the brain from various medieval periods and geographies. Interpreting these from a mental health angle reveals a different way to view how the compartments of the brain were visualized. Skulls themselves could be sites for discussion about such conditions as PTSD. We certainly have many that reveal the impact of weapons from battles or tournaments, speaking to the physical trauma involved in certain types of PTSD. This method, however, is fraught with issues concerning the display and interpretation of human remains and is not one to utilize without careful thought.

Another potential way to invoke historical mental disability is through locations. For instance, Geel, in Belgium, is famous as the site of the martyrdom of Saint Dymphna. After her death at the hands of her father in the seventh century, Geel became known as a destination for those with mental disability or mental health issues. Dymphna herself became the patron saint of mental health. Those who visited Geel were housed either in the hospital or, when that filled up, in the houses of welcoming community members – a practice that continues today. Photographs of the church, Dymphna’s relics, and related sites certainly would help tell this story.

For me, finding Kadir Attia’s “Schizophrenic Melancholia” reemphasized the need to imagine ways to curate historical and medieval mental disability. The history of mental disability is not a static subject confined to musty manuscripts, but the lived experience of a community of people who have spent too long being told their heritage is impossible to represent.

[i] There are plans to depict Saint Dymphna in this particular series.

[ii] Merchant Culture in Fourteenth-Century Venice: The Zibaldone da Canal, ed. and trans. John Dotson (Birmingham: Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies, 1994), 149-151.

Bio:

—Kisha G. Tracy is an Associate Professor of English Studies at Fitchburg State University in Massachusetts, specializing in early, especially medieval, British and world literatures. In addition to several articles, her first book, Memory and Confession in Middle English Literature, was published by Palgrave in 2017. Her main research interests include medieval disability, particularly mental disability, and the scholarship of teaching and learning.