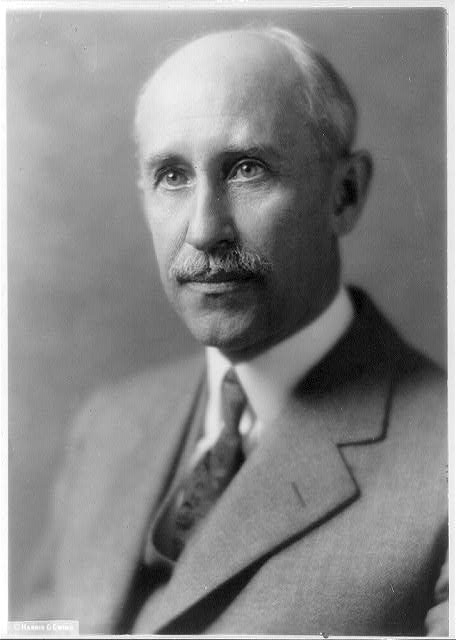

Like feminist scholars and LGBT scholars before us, scholars of disability history want a usable disabled past. This shared desire comes from similar roots. Disability has long been erased from the historical record, whether because said disability was seen as a shameful secret, or whether that disability was not recognized for what it was by contemporary medical science. In her 2013 book Conditions Are Favorable, Tara Staley speculated that one or both of the Wright Brothers may have been on the spectrum of autism. More specifically, Staley speculated that they may have suffered from Asperger’s syndrome. This article will address the question of viewing Orville and Wilbur Wright (primarily Orville, pictured below) through the lens of disability and more generally discuss the merits and flaws of “claiming” historical figures for disability studies.

Claiming the past is an important subject for those of us engaged in the history of dispossessed communities. By “claiming,” I mean a deliberate effort to rebuild a community’s continuity that involves building a history to link our present to a past obscured by time, space, and sometimes wildly different worldviews. I see efforts by historians of disability to claim the past by finding lost stories of disability in much the same vein as historians of sexuality doing the same for lost stories of LGBTQ people and places. This is a laudable historigraphic task, but it must be done carefully.

If we dig deeper than the cardboard cutout image of the Wrights we meet in elementary school, we learn that the Wrights were unlike other men. In 1930, it was reported by a journalist writing for the New Yorker that “The first man ever to fly an airplane is a gray man now, dressed in gray clothes. Not only have his hair and his mustache taken on this tone, but his curiously flat face, too. Thirty years of hating publicity and its works, thirty years of dodging cameras and interviews, have given him what he has obviously wished for most: a protective coloration which will enable him to fade out of public view against a neutral background. Orville Wright is not merely modest; he is what the sociologists call an asocial type.”1 The journalist’s observations echoed memories of Orville going back to his high school days in Dayton in the 1880s, where friends remembered Orville watching their parties without ever actually joining him. Orville was famously reluctant to speak in public, even at occasions commemorating Kitty Hawk, when as the last surviving Wright he’d become a demigod in the eyes of an aviation-loving public. Wilbur enjoyed speaking in public more than Orville did, but even he kept his speeches limited to the subject of aviation.

“My brother and I do not form many intimate friendships, and we are loathe to give them up,” Wilbur Wright wrote to Octave Chanute in 1910 – he wasn’t speaking idly. And the brothers weren’t just shy. Orville and Wilbur were lifelong bachelors, highly unusual for men of their class and generation. Beyond this, they were both highly and unusually fastidious. They were teetotalers who didn’t smoke tobacco or work on Sundays, with Orville writing cheerfully to their father during an early trip to Paris that “We have been real good over here. We have been in a lot of churches, and haven’t gotten drunk yet!”2

Their fastidiousness was more than just their cultural Christianity at work. Wilbur refused to eat on his first boat ride to Kitty Hawk out of disgust for the offered fare and the cleanliness of the boat. He had a personal routine that his family’s maid-of-all-work would remember in great detail in the authorized family memoir published decades after Wilbur’s death. Orville too was deeply concerned about his diet and would “tease” the family servant for decades for watering down his milk upon his first return from Kitty Hawk. Orville also was a “dandy” who methodically scrubbed his face with lemon juice after every visit to Kitty Hawk to remove any trace of unfashionable suntan. Orville always looked as if he’d stepped “right out of a band box,” his niece Ivonette remembered decades later. (The Wright insistence on personal grooming sometimes caused them trouble – perpetually “Mr. Wright” to their Kitty Hawk neighbors, the badge of respectability that was their clothing sometimes got them into trouble with local merchants.)3

If the Wrights were determined to maintain control of what they ate and what they dressed, they were no less determined to maintain control of their work and their legacy. Through much of their career, the Wrights refused to let anyone but themselves work on their flying machines. In 1908, in the midst of international labor when he was already an aviation superstar, Wilbur wrote to his sister Katharine that “People think I am foolish because I do not like the men to do the least important work on the machine. They say I crawl under the machine and over the machine when the men could do it well enough.” Wilbur often lamented how critical and his brother could be – and the way this often alienated them from others. In the 1930s and 1940s, Orville Wright had largely disappeared into retirement in Dayton. And only the threats to the family legacy of aviation could stir him – his willingness to fight in court and in public opinion over historical credit for the first flight at Kitty Hawk soon became legendary.4

Introverted creatures of habit, fastidious in their personal grooming and professional lives, uninterested in deep philosophy, the Wrights have recently been placed “on the spectrum” by twenty-first-century observers. But one could just as easily make opposing arguments for all the above points. Orville’s adult shyness could easily have been a product of the chronic pain and depression he suffered due to Wilbur’s death or his own serious injuries as an early pilot. Or, he may have been shy because he was a leading bishop’s youngest son. The food Wilbur refused to eat on the boat trip to Kitty Hawk may well have been rancid, given the time, place, and era. That Wilbur and Orville consciously asserted their class through grooming and deportment among the working-class people of Kitty Hawk was not terribly unusual given their backgrounds. By the same token, Wilbur’s desire to build his own plane and Orville’s to protect the family legacy may have come from a desire to stay alive – both in the air and in the pages of history. Their lifelong bachelorhood was certainly unusual and their personalities often critical, but bachelorhood and acerbic personalities do not a diagnosis make.

On the question of whether or not the Wrights were neurotypical (i.e., on the spectrum of autisim or not), I take no particular position. There is some fascinating evidence to suggest that they may well have been on the spectrum – but not enough for us to make a firm diagnosis one way or another. And perhaps historians shouldn’t be in the business of playing diagnostician anyway. As one psychiatrist has written, “It is difficult enough to make accurate diagnoses of autism or Asperger’s disorder in real life, with face-to-face interviews and comprehensive testing, let alone trying to apply post-mortem diagnoses, sight unseen. Retrospective medical diagnoses are always problematical and suspect.”5 We can offer no sure diagnosis about the internal lives of the Wright Brothers – anymore than we can firmly declare that James Buchanan or Abraham Lincoln might have identified as queer.

But even if we cannot answer the question, “Were the Wright Brothers neuroatypical?,” the asking is still a worthy task for historians. Their perceived eccentricity illuminates perceptions of genius and manhood in America at the dawn of the twentieth century, just as our reactions to them illuminates the way we often medicalize behavior at the beginning of the twenty-first. Those looking for representation in the past can certainly use Wilbur and Orville, just not in the name of categories like Asperger’s and autism that did not exist in their lifetimes.

Having said all this, I’m not ready to abandon the idea of historians of disability engaging in the act of retrospective diagnosis. The challenge with the Wrights and similar pop diagnoses of historical figures being “on the spectrum” is that the line between eccentric and neuroatypical has fluctuated wildly in the last few decades. One generation’s quirks may be another’s medical diagnosis, and in the moment ourselves, it’s hard to know who falls into what category. We stand on surer diagnostic ground when we can point to more objective standards than unusual behavior (as, for example, with inventor Nikola Tesla’s self-reported hallucinations) – but then the quest for objective standards of behavior is itself a difficult one.

In the end, we can make no sure statements about the inner lives of the Wright brothers. But historians rarely have certainty. What we can have is arguments, backed by historical evidence, that let us shed light on the stories of the past to better illuminate our present, and to find the hidden stories of eccentricity and disability long neglected by our intellectual predecessors.

—Dr. Mike Davis is an assistant professor of history at Hampton University, where he teaches American cultural, diplomatic, and intellectual history. His current project is the first scholarly biography of Virginia Beach’s own Edgar Cayce, “the greatest psychic who ever lived in America.” He can be reached at michael.davis@hamptonu.edu and followed on Twitter at @madavis71415872.

- Eric Stephens, “Heavier than Air,” The New Yorker, December 13, 1930, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1930/12/13/heavier-than-air.

- Wilbur Wright to Octave Chanute, April 28, 1910, and Orville Wright to Milton Wright, August 23, 1907. Library of Congress.

- Fred C. Kelly, ed., Miracle at Kitty Hawk: The Letters of Wilbur and Orville Wright, 1951 (New York: De Capo Press, 1996), 47; Tom D. Crouch, The Bishop’s Boys (New York: Norton, 1989), 112; and Orville Wright to Katharine Wright, October 4, 1903, Library of Congress.

- Wilbur Wright to Katharine Wright, September 20, 1908, Library of Congress.

- Darold A. Treffert, “Savant Syndrome 2013 – Myths and Realities,” https://www.wisconsinmedicalsociety.org/professional/savant-syndrome/resources/articles/savant-syndrome-2013-myths-and-realities/”.