On September 10, 1830, the artist Martha Ann Honeywell arrived in Louisville, Kentucky, after a long journey from Baltimore via road, packet boat, and rail. First, she rented a “large room” on Wall Street to display her papercutting and embroidery for sale. Then, Honeywell placed an advertisement in the Daily Louisville Public Advertiser.

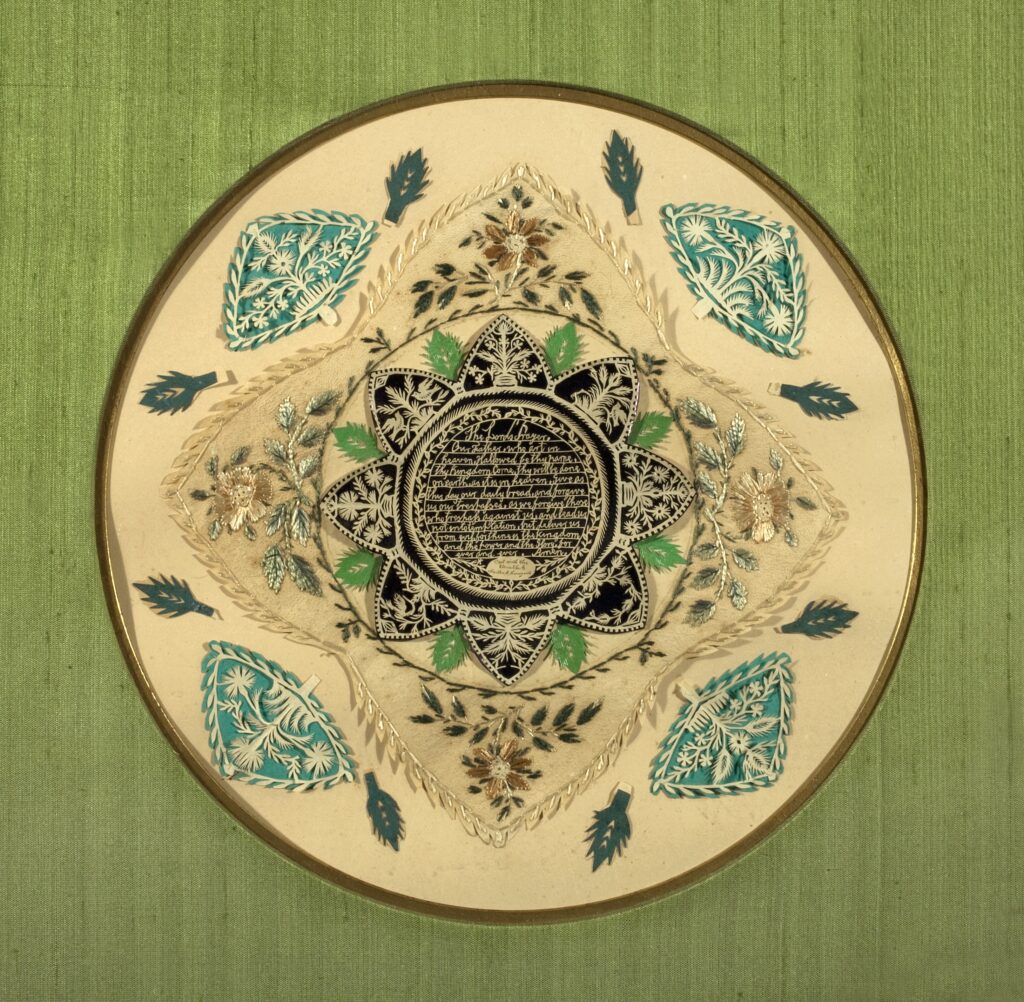

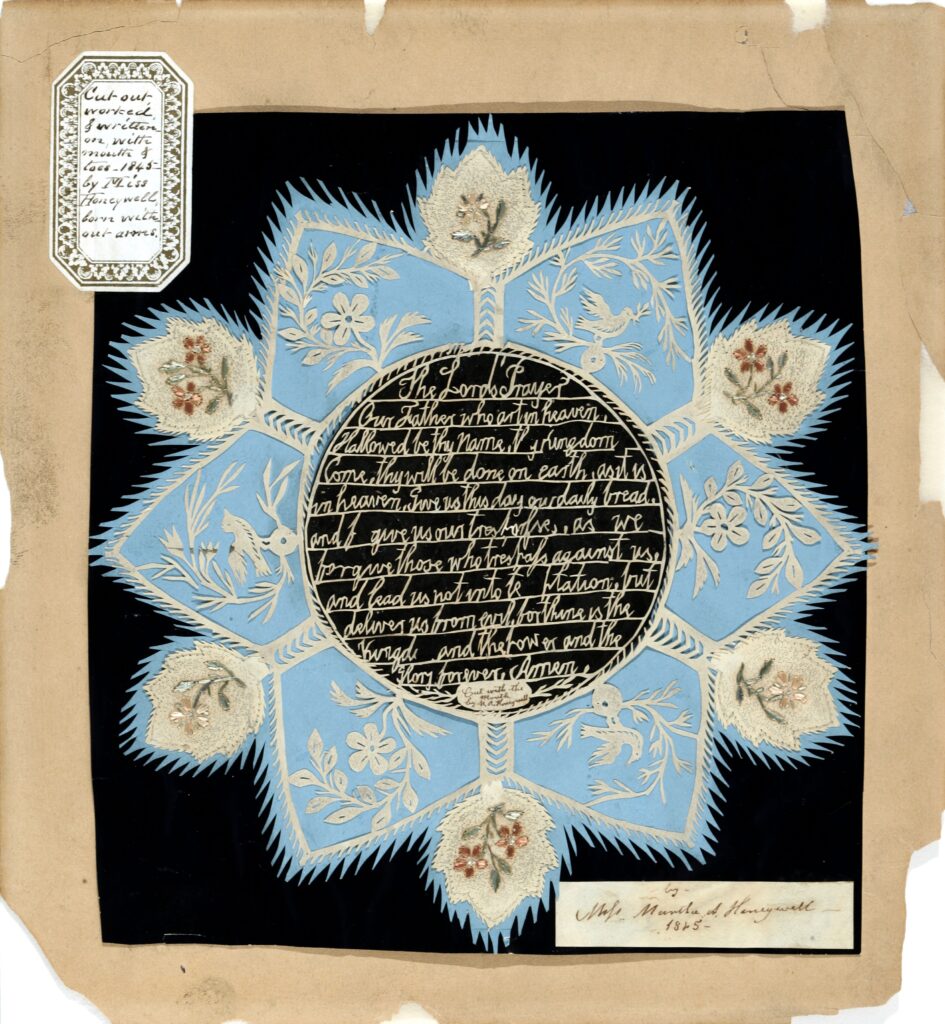

“Though born without arms,” she wrote, “this Lady…has acquired such use of a common pair of Scissors, by holding them in her mouth, as to be able to cut out of paper, the most curious and difficult pieces of cutting—such as watch papers, flowers, landscapes, and even the Lord’s Prayer—perfectly legible, not only the out lines, but to resemble copper-plate engraving.”

Working without arms and hands (and with only one foot with three toes), then, Honeywell created extraordinarily detailed artwork, captivating the many Louisville residents who soon frequented her establishment with her surprising confluence of artistic ability and physical disability.

Louisville was only one stop on Honeywell’s tour. Born in 1786 in New York, she traveled nearly continuously between 1798 and her death in 1856, attracting patrons across the United States, Canada, France, Germany, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom with her creative skills and unusual physique. A celebrity during her time, Honeywell’s work received rave reviews, she performed for nobility and royalty, and, over the course of it all, she earned a sizable profit.

Perhaps just as importantly, Honeywell retained independent control over her travels, exhibitions, finances, publicity, and art, which allowed her to personally benefit from her successes. At a time when few women could pursue careers as professional artists and showmen increasingly exhibited disabled people as freakish oddities, Honeywell primarily toured and performed by herself: a lone itinerant disabled female artist navigating the American and European art worlds.

Honeywell’s story is remarkable, drawing together the histories of art, performance, disability, business, and travel in ways that may be as surprising for readers today as they were for audience members first entering one of her shows in the nineteenth century. Despite her uniqueness, however, she was not the only nineteenth-century artist who built a career on the seeming juxtaposition of artistic ability and physical disability.

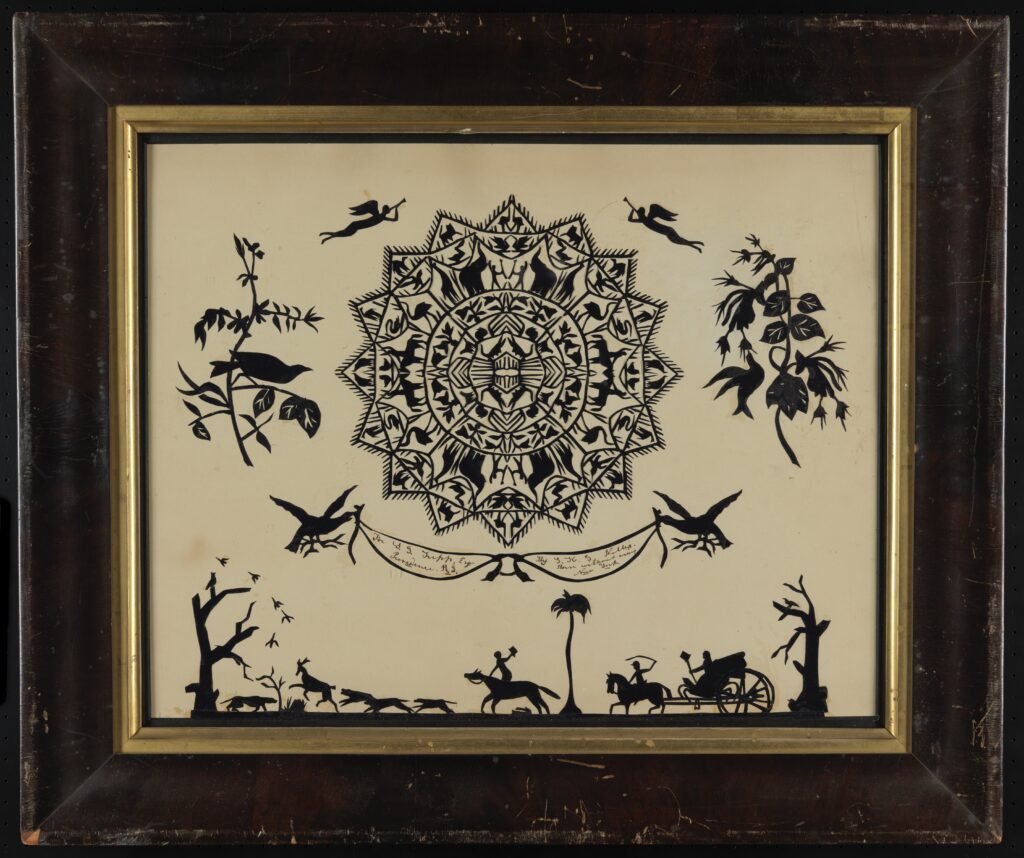

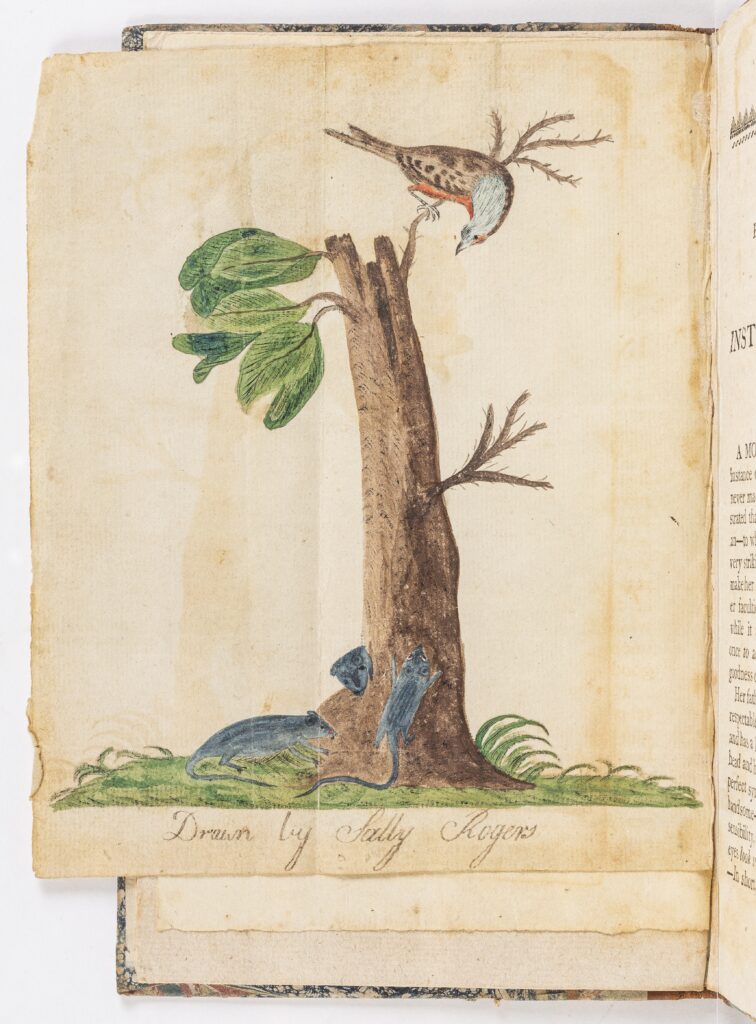

From 1806 to 1813, Sarah Rogers, who did not have use of her arms and legs, toured the United States attracting acclaim for the paintings and silhouettes she made with her mouth. In addition, between 1828 and 1865, Saunders Ken Grems Nellis, who was of distinctly shorter stature and without arms and hands, traveled across North and South America and Europe, showcasing his skills in papercutting, music, and dance. Like Honeywell, these artists were self-managed, profitable, and widely celebrated.

Together, their stories push us to think in new ways about what was possible in the increasingly connected world of the nineteenth century. Advances in transportation, print advertising, and a growing market for culture enabled these artists’ careers. So too, perhaps paradoxically, did patrons’ ableist fascinations with their bodies. Customers brought negative assumptions about physical difference to these artists’ shows and drew on popular Linnaean systems of classification to evaluate their humanness and locate their place in the natural world.

Yet Honeywell, Rogers, and Nellis transformed these prejudiced curiosities into artistic opportunities. Working not as sideshow “freaks” but rather as independent artists, managers, and contractors, they cultivated distinguished careers.

Despite Honeywell, Rogers, and Nellis’s successes during their lifetimes, their stories have long remained buried in the archives. A major impediment to recovery has been that, because of their itinerancy, their artwork, correspondence, and personal records are housed in dozens of libraries and museums across multiple countries. Recapturing their stories, then, requires significant archival work and may only have been fully possible with the development of digital collections, which allow researchers to broadly assess their travels and better identify surviving artworks.

Honeywell, Rogers, and Nellis’s resulting obscurity, then, is why we (Laurel Daen and Marianne Petit) were not only thrilled to discover their work independently about a decade ago, but also why we decided to collaborate to tell their stories through a creative project we’ve titled “Mouth & Toes: The World of 19th-Century Artists with Disabilities.” A collection of moving panoramas, large format accordion books, and handheld flipbooks as well as an eBook and virtual exhibition, the project traces the lives and careers of these artists as they traversed countries and continents selling their wares.

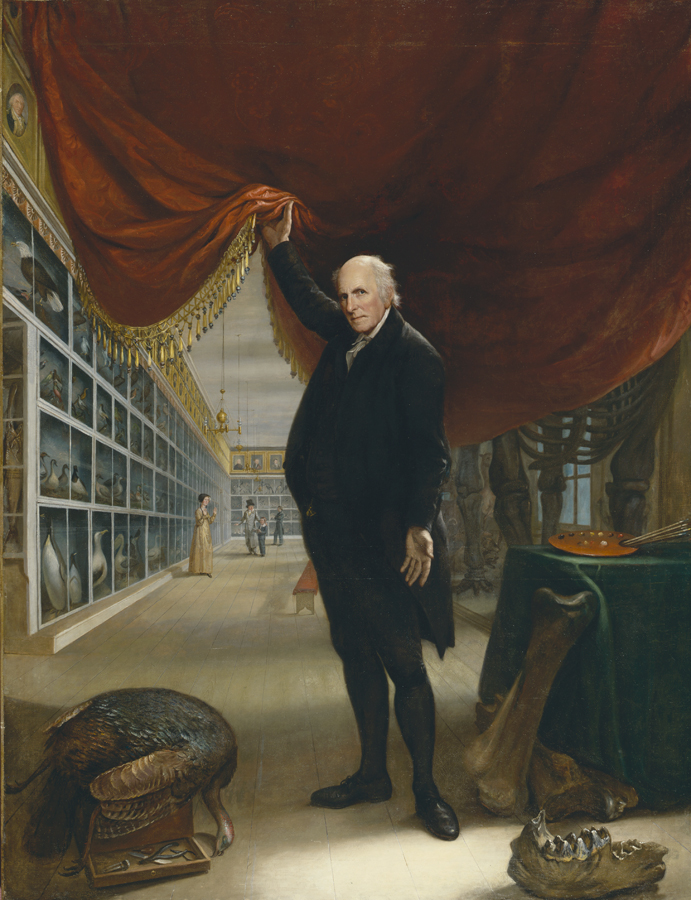

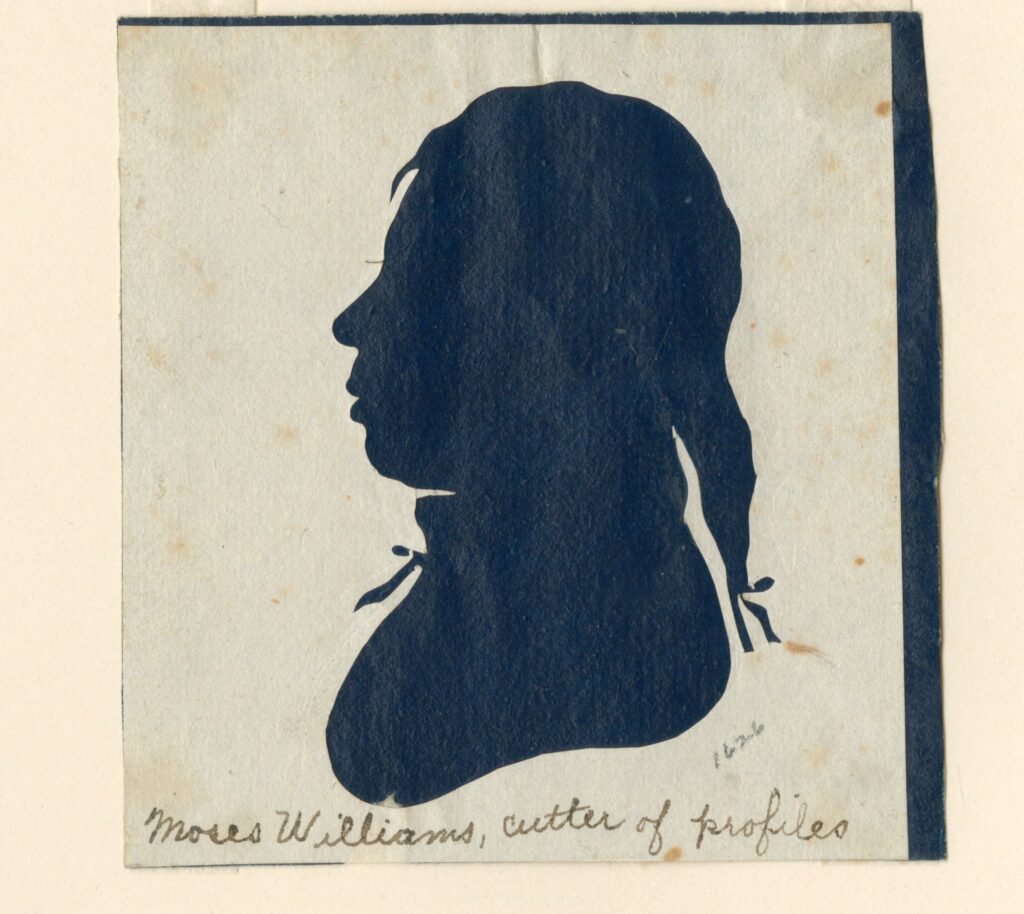

“Mouth & Toes” also contextualizes Honeywell, Rogers, and Nellis’s stories in the larger nineteenth-century worlds of art, performance, disability, business, and travel. Viewers encounter Charles Willson Peale and his famed Philadelphia Museum which collected Honeywell and Rogers’s work. They also meet Moses Williams, a man formerly enslaved by Peale who was, like the featured artists, a master paper-cutter. These and other figures bring Honeywell, Rogers, and Nellis’s journeys to life, giving readers a glimpse into what it might have been like to enter one of their exhibitions so long ago.

Because Honeywell, Rogers, and Nellis’s artwork was primarily paper-based, “Mouth & Toes” is, too. The narrative is told through silhouettes and displayed on a moving panorama, a popular nineteenth-century form of entertainment in which a long painted scene, or scroll, is rolled between two large dowels and slowly unfurled. The work includes animated handheld flipbooks that depict how Honeywell, Rogers, and Nellis might have created their art—threading a needle with their toes, for example, or painting with their mouth.

The paper-based nature of “Mouth & Toes” was also accessible and practical. As a project that centers disabled artists, we prioritized accessibility. Using readily available materials, such as paper and cardboard, moved us toward this goal. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic unintentionally shaped our choice of medium. Marianne Petit designed the first moving panoramas during lockdown in the summer of 2020. Without access to tools and a studio, she built them in her one-bedroom apartment while sitting at her kitchen table.

Events during the summer of 2020 also shaped the development of our narrative. With the COVID-19 pandemic there was a surge of eugenical discourse across the nation that represented disabled people as expected casualties of the disease and used disability to rationalize their death. Reports of medical rationing revealed the very real effects of this discourse. At the same time, Black Lives Matter protests erupted across the country. These dual developments acutely reminded us of the links between ableism and racism, a theme we then highlighted in the narrative.

“Mouth & Toes” begins with a short introduction and then, moving chronologically, transports viewers to Honeywell’s first exhibition in New York City when she was just twelve years old. At Gardiner Baker’s American Museum, surrounded by taxidermied animals and scientific contraptions, she performed her skills in needlework for curious onlookers. From this inauspicious beginning, the narrative traces how Honeywell used early national advances in transportation, advertising, and commerce to perfect her artwork and expand her shows to other cities.

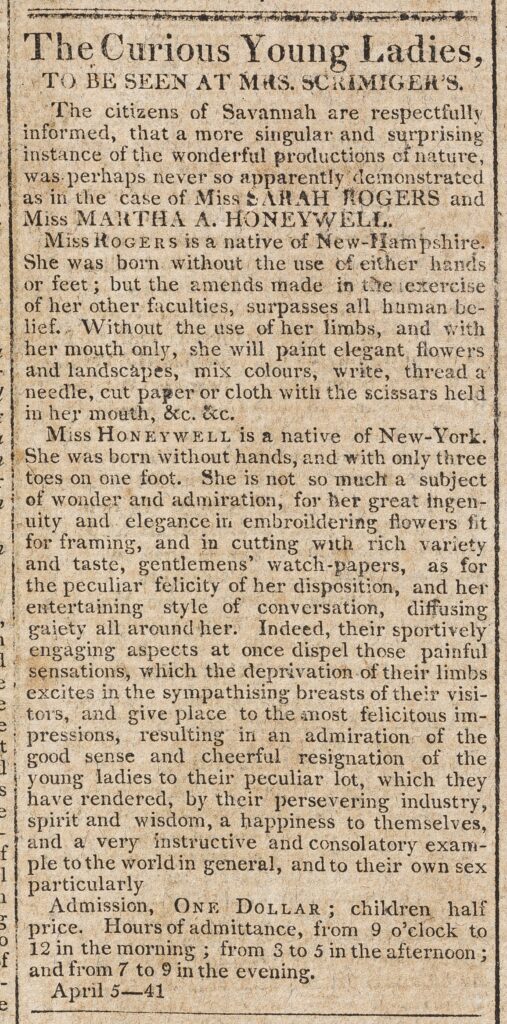

In 1808 in Charleston, SC, Honeywell met Rogers and they organized a joint exhibition. Calling themselves the “Curious Young Ladies,” they sold patrons needlework and cutwork samples along with performances of their atypical physiques. Honeywell and Rogers split when Honeywell traveled to Europe and Rogers to Philadelphia, then the center of the American art world. In Philadelphia, Rogers connected with Charles Willson Peale and contributed works to the Society of Artists’s exhibitions. Unfortunately, it was also there that she died unexpectedly in 1813.

Charles Willson Peale was a supporter of both Rogers and Honeywell’s artwork and so “Mouth & Toes” also chronicles his story. Peale gained prominence as a portrait painter in the 1760s and then launched the Philadelphia Museum, the nation’s first art and natural history museum, in 1784. A scientist, naturalist, inventor, and painter, Peale was attracted to Rogers and Honeywell’s work because of his dual interests in art and the natural world. Compelled by their capacities to make art despite their physical limitations, he theorized about the wonders of nature to compensate for loss.

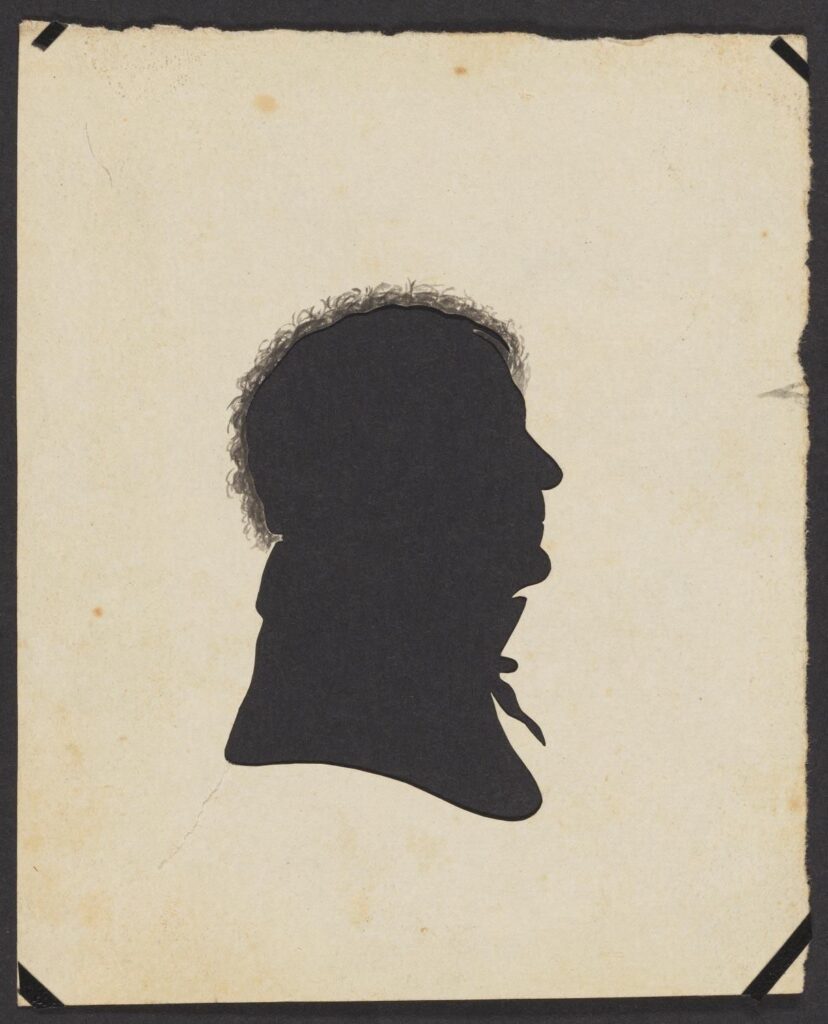

The fame that Rogers garnered for her paintings and papercuttings before her death would not have matched that of another Philadelphia-based paper-cutter: Moses Williams. Formerly enslaved by Peale, Williams cut profiles at the Philadelphia Museum with a physiognotrace, a newly designed machine that traced sitters’ silhouettes and reduced them in size, allowing the user to produce hollow-cut likenesses. Williams ostensibly received his freedom from Peale in 1803 because of his artistic skills, and he continued cutting silhouettes at the Museum until close to his death in about 1825.

“Mouth & Toes” suggests similarities between Williams’s exhibitions and those of Honeywell, Rogers, and Nellis. Although Williams was not physically disabled, white museumgoers viewed him, like Honeywell, Rogers, and Nellis, as both artist and object. Customers examined Williams’s body as they did the other animals, insects, and minerals on display. In addition, patrons were fascinated by his artistic abilities in part because of his black skin. Just as audience members’ negative assumptions about disability heightened the surprise with which they viewed Honeywell, Rogers, and Nellis’s art and techniques, racial prejudice led visitors to anticipate Williams’s artistic inferiority, an assumption he provocatively challenged.

The narrative continues by chronicling Honeywell’s sixteen-year journey to Europe in which she visited England, Ireland, France, Germany, and Switzerland, performed for nobility and royalty, and perfected her visual art. During that time, she composed one of her most famous pieces: a papercutting of the words and letters of the Lord’s Prayer surrounded by ornamental birds and flowers. When Honeywell returned to the United States in 1827, patrons heralded her artwork as “most curious and difficult” and described her as a celebrity who was “admired and carressed” [sic] (Baltimore Gazette and Daily Advertiser, November 6, 1828).

Honeywell and Nellis crossed paths in 1828 in Baltimore. Nellis was just getting his start at only eleven years of age, but viewers already described his shows, which combined papercutting, music, and dance, as evidence of “extraordinary genius” (Baltimore Patriot, December 18, 1828). Soon he traveled to perform in the American South and internationally in Canada, the Caribbean, and Europe. The ever-expanding transportation network made these voyages easier for him than Honeywell and Rogers had experienced in earlier decades. Nellis also married a female customer and she accompanied him on these journeys.

“Mouth & Toes” posits that the more established museum and sideshow industry of the mid-nineteenth century affected Nellis’s shows. Performing at these institutions more often than Honeywell and Rogers, Nellis likely gained more security in attracting clients but less control over his exhibitions and profits. At some institutions, Nellis performed alongside African, Native, and Hispanic peoples whom showmen exhibited for their racialized features. Again, ableism and racism entwined as white audience members marveled at Nellis’s body just as they did the racially othered men and women on view.

![Printed poster advertising "Master Nellis, born without [arms]" Images include white men without arms. Advertisement on same page includes images of Black men in ostensibly comic poses.](https://allofusdha.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Nellis-9-and-10-1024x946.jpeg)

Nellis and Honeywell, who was still touring, spent the last decades of their careers traveling internationally, perhaps in an effort to exhibit where museums and sideshows were less common and the artists had more independence. Honeywell voyaged to Canada in the late 1840s and early 1850s before her death in 1856. Nellis traveled throughout Central and South America in the late 1850s and early 1860s before passing away in Bolivia in 1865. The artists were eulogized as “world-renowned wonder[s]” and gifts of the “natural world” (New York Times, April 9, 1866).

As we (Laurel Daen and Marianne Petit) traced Honeywell, Rogers, and Nellis’s stories in text and art, we were struck by the power of disability as a source of creative inspiration and profit. Certainly, customers approached these artists’ exhibitions with negative assumptions about disability and understood their capacity to overcome their physical disabilities as a primary accomplishment. Such responses highlight the deeply rooted ableism in American culture and beyond during the period, which these artists’ contended with over their lives.

Yet Honeywell, Rogers, and Nellis also used their customers’ prejudices for greater access, opportunity, and autonomy. Taking advantage of a unique historical moment when technological and cultural developments made travel and exhibition possible but before showmen and museum operators limited their creative and financial independence, these artists used their bodies as sources of artistic inspiration and attraction, cultivating successful and profitable careers.

We (Laurel Daen and Marianne Petit) felt that this message of disability as fuel for artistic production and accomplishment was so powerful that we ultimately decided to complement the paper-based works of Mouth & Toes with a virtual component. With the continuing COVID-19 pandemic, we realized that few people, especially those who were disabled or high-risk, would be able to view our work at in-person indoor exhibitions. Moreover, print formats can be difficult to navigate for readers with disabilities. To share Mouth & Toes more broadly, then, we transposed the moving panorama into an eBook and curated virtual galleries of Honeywell, Rogers, Nellis, Peale, and Williams’s artwork.

The eBook and virtual galleries are freely available on our website: Mouth & Toes: The World of 19th-Century Silhouette Artists with Disabilities. We hope that viewers engage with these materials, download and manipulate them, and use accessible technology to connect with them in ways that would not be possible in a physical format. The mission of “Mouth & Toes,” after all, is to share Honeywell, Rogers, and Nellis’s stories and artwork widely. We have found personal inspiration and direction from their histories and art. We hope that “Mouth & Toes,” in physical and digital formats, brings the same to readers and viewers.

Further Reading

Bogdan, Robert. Freak Show: Presenting Human Oddities for Amusement and Profit. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988.

Brigham, David R. Public Culture in the Early Republic: Peale’s Museum and Its Audience. Washington, D.C. and London: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995.

Carrick, Alice Van Leer. A History of American Silhouettes: A Collector’s Guide, 1790-1840. Rutland, V.T.: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1968.

Daen, Laurel. “Martha Ann Honeywell: Art, Performance, and Disability in the Early Republic.” Journal of the Early Republic 37, no. 2 (Summer 2017): 225-250.

Jaffee, David. A New Nation of Goods: The Material Culture of Early America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010.

Kelly, Catherine E. Republic of Taste: Art, Politics, and Everyday Life in Early America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016.

Lanning, Anne Digan. “Sally Rogers: The Celebrated Paintress.” Historic Deerfield 13 (Summer 2012): 2-7.

Sacco, Ellen. “Racial Theory, Museum Practice: The Colored World of Charles Willson Peale.” Museum Anthropology 20, no. 2 (Fall 1996): 25-32.

Sellers, Charles Coleman. Mr. Peale’s Museum: Charles Willson Peale and the First Popular Museum of Natural Science and Art. New York: Norton, 1980.

Shaw, Gwendolyn DuBois. “Moses Williams, Cutter of Profiles: Silhouettes and African American Identity in the Early Republic.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 149, no. 1 (March 2005): 22-39.

Thomson, Rosemarie Garland, ed. Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body. New York: New York University Press, 1996.

Verplanck, Anne. “The Social Meanings of Portrait Miniatures in Philadelphia, 1760-1820.” In American Material Culture: The Shape of the Field, edited by Ann Smart Martin and J. Ritchie Garrison, 195-223. Winterthur, D.E.: Winterthur Museum, 1997.

Laurel Daen is an Assistant Professor of American Studies at the University of Notre Dame, where she is affiliated with the Program in Gender Studies and the John J. Reilly Center for Science, Technology, and Values. Her research and teaching focus on disability, sickness, medicine, and health in America, primarily during the 18th and 19th centuries. She is currently completing her first book, which examines the exclusion of disabled people from legal and political rights in early America. Laurel has published articles in the Journal of Social History, Journal of the Early Republic, Early American Literature, and History Compass.

Marianne R. Petit is an artist and educator whose work explores fairy tales, the body, graphic and narrative medicine, as well as collective storytelling practices through mechanical books that combine animation and paper craft. Her movable books can be found in museum, library, and university collections. She is an Arts Professor at New York University’s Interactive Media Arts (IMA) and Interactive Telecommunications (ITP) programs located within the Tisch School of the Arts.