The first recorded study of poor posture—dubbed the “The Harvard Slouch” study—appeared in 1917. University physicians found that 80 percent of students exhibited significant bodily misalignments that, if left untreated, would lead to life-threatening disease and permanent disability. In the decades to follow, the U.S. military, secondary schools, industrial workplaces, and public health agencies would conduct similar studies, each coming to the same conclusion that slouching was rampant in America.

In other words, there was a poor posture epidemic gripping the United States, from the early twentieth century until the 1970s.

For years I have attempted to explain this epidemic, devoting my time to understanding the 80 percent. That is a lot of disabled people, even by today’s standards. Currently, the Center for Disease Control estimates 26 percent of the American population to be disabled. A trained historian of science, I know not to take statistical findings at face value. A lot goes into producing seemingly simple and straightforward data. A method of measuring human posture had to be created and agreed upon. Tools had to be standardized. And most importantly, people in powerful positions had to persuasively articulate the need for such examinations and what they revealed about human health to bring about political, financial, and cultural buy-in.

Most pressing in my mind was whether anyone labeled with poor posture actually believed that it was a disabling health problem. Did they feel limited in their work, social, or home life? Collecting testimonies from a variety of sources, I came to learn that even those who felt healthy but had slight, yet visible spinal curvature faced significant discrimination in work and society, including being barred from housing, employment, the military, and places of higher education. Some, with great pain, talk of romantic rejections, feeling a great sense of shame for the very existence of their curved backs and knobbed limbs.

What I had not considered until very recently, though, was the remaining 20 percent. Committed to social history, I am drawn to the have-nots, not the haves. So it is little wonder that I kept my focus on all those deemed disabled. But what was I missing by overlooking those categorized as able, normal, and nondisabled?

The gestalt shift felt familiar. Almost immediately I thought of how in 1989, women’s studies scholar Peggy McIntosh “flipped the script” in her now classic article “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack.” She and other scholars went on to demonstrate the often unseen yet multitudinous ways whiteness automatically confers advantage, construed as a normative and neutral category.

Of course, disability studies is no stranger to normativity. Beginning in the 1990s, scholars such as Lennard Davis and Rosemarie Garland Thomson wrote about how the concept of the normal—or the “normate”—was largely an invention of the nineteenth century, when the rise of statistics and industrialized capitalism, as well as the popularity of “freak” shows, reinforced a blunt classificatory system, drawing a stark line between normality and abnormality. In an attempt to loosen the grip of this historical development—which we still live with today—critical theorist Robert McRuer offers the frame of “compulsory able-bodiedness” in order to denaturalize normativity. When the normal becomes natural, McRuer contends, a kind of hegemony of ability takes hold, a system and culture in which able-bodied identities are always and everywhere “preferable and what we all, collectively, are aiming for.” In such a society, the question of whether a person would rather be hearing, sighted, or neutrotypical is always answered in the affirmative, and without hesitation

And yet, as McRuer and other disability scholars make clear, the goal of being able-bodied is largely a pipe-dream, a notion of perfectibility that can never be achieved.

The fantasy of able-bodiedness is fed by fear and avoidance. As finite beings, we all know that physical and mental impairment is an ever-present possibility, if not an already lived reality. But even if ableness is a fiction, it is one that has a significant bearing on the material world. The ability-disability binary is reified every day in the clinic, in welfare policy decision-making, and in schools. And much like the presumed sunny side of many other binaries—heterosexuality, maleness, whiteness—ability confers implicit and explicit privilege.

But what is ability? Is it simply something you know when you see it?

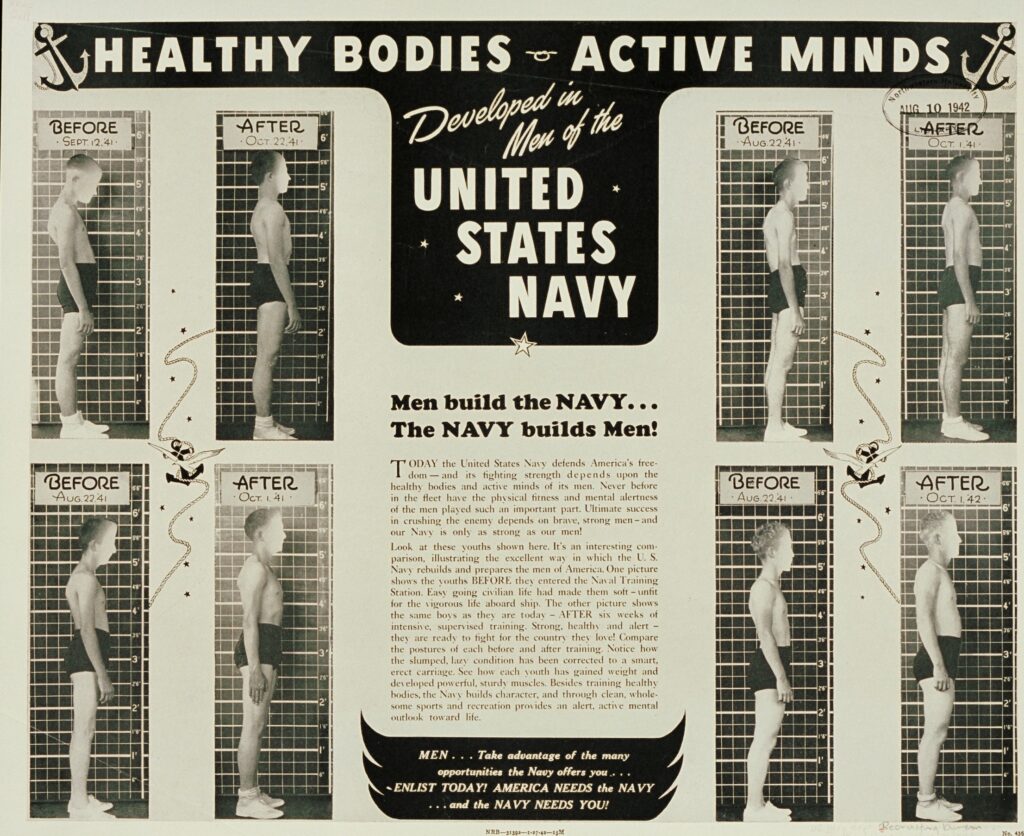

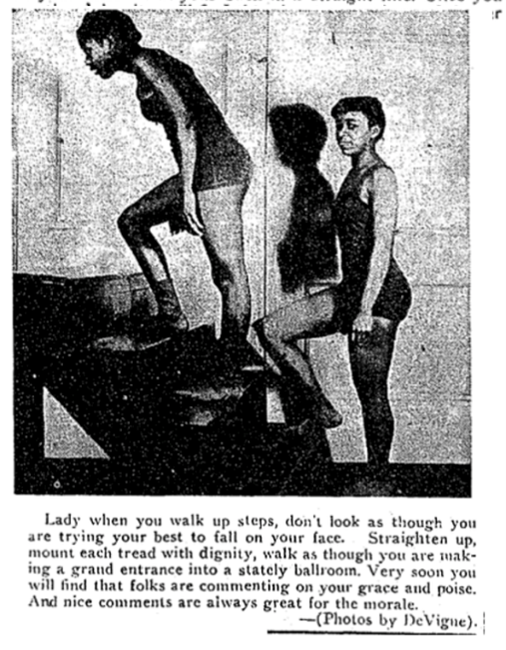

The posture scientists that I study thought so. And they made a point of training other non-experts to see it too, engaging in a process of visual recruitment. Using one’s vision (yet another aspect of ableism inherent to the posture crusade), an onlooker could determine able-bodiedness by whether or not the examined subject could assume plumbline verticality, with the head, shoulders, chest, pelvis, and feet stacked one on top of each other, all in alignment.

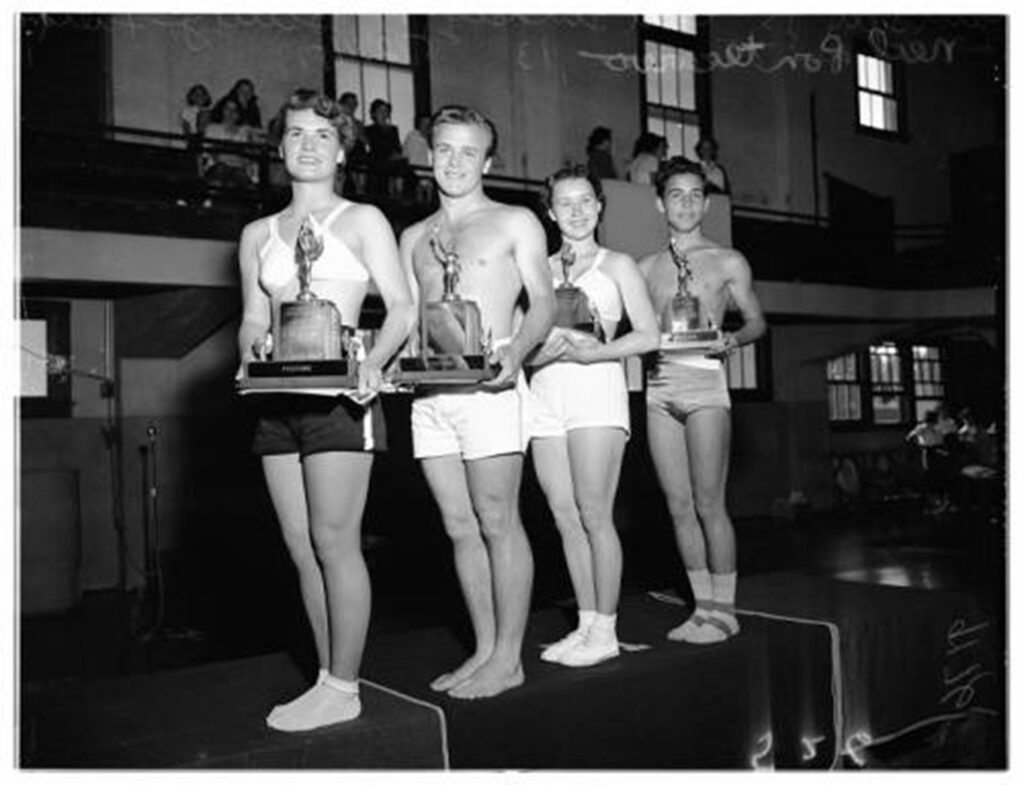

What started as a clinical science quickly became popularized through posture queen and king contests, competitions in which the standards of able-bodiedness and normativity were reinforced and celebrated. Judges came from the ranks of medical doctors, nurses, beauty specialists, clergy members, and townspeople. Participants, sometimes scantily dressed, paraded in front of the judges, walking as if balancing a book on top of their heads. In the scheme of fitness tests, the achievement of perfect posture was not as demanding as, say, doing a certain number of chin-ups, a staple of the post-World War II era of Presidential fitness tests. Except for the posture contests sponsored by the American Chiropractic Association (ACA)—for which contestants needed to present x-ray proof of their spinal perfection—most perfect back contests operated on simple principles, the human form judged by a quick glance of the eye.

Kirkland/Time Archives, public domain.

We often think of ability as doing, as taking action. Standing up straight, comparatively speaking, seems remarkably static. But to posture crusaders it served as a key foundation for making things happen. If I have learned anything from these posture contests, it is that ability conjured up just as many imagined futures as disability did. Good posture was thought to assure heterosexual marriage and children, as well as a steady job. The ACA’s perfect back contest, for example, came with a cash prize and a scholarship to attend chiropractic school, giving many female contestants the opportunity to enter the professional workplace, a prospect that was often otherwise out of reach. At Howard University during the World War II years, physical educator Maryrose Reeves Allen trained Black undergraduate women in proper poise, believing that with good posture they could overwrite history, undoing the physical and psychological degradation brought about by the legacy of slavery, oppression, and prejudice. Good poise was no match for the structural racism and sexism entrenched in U.S. society, but that didn’t stop women like Allen, and generations that followed her (like Amy Cuddy today), from believing that it could.

Eventually good posture would wane as a meaningful measure of ableness. By the post-war years, it would be replaced by more athletic measures, with greater emphasis placed on body weight than form. In many ways, the poor posture epidemic was the precursor to today’s so-called obesity epidemic, with shifting norms of abled-bodiedness arising and fading along the way.

In the past decade, historians have made great gains in exploring the changing meaning of disability over time and place. But in order to denaturalize the notions of both normativity and disability, it seems that attending to the fluctuating meanings of ableness is equally important, a move that would be similar to what scrutiny of whiteness brought to race studies three decades ago. The question of who counts as able-bodied, and the contingent metrics and cultural assumptions inherent to such a verdict, seems particularly important, especially since, to use McRuer’s words, “compulsory able-bodiedness produces disability.” The study of ableness has the potential to expose the cracks and contradictions in the edifice of normality, demonstrating that most people over the course of their entire lifetime will fall somewhere in between the artificial poles of abled and disabled.

Beth Linker is the Samuel H. Preston Endowed Term Associate Professor at the University of Pennsylvania in the Department of History and Sociology of Science. Her research and teaching interests include the history of science, medicine, disability, health policy, and gender. She is author of War’s Waste: Rehabilitation in World War I America (Chicago, 2011) which was featured in Ric Burns’ 2015 documentary, A Debt of Honor. Linker’s next book, Slouch: Fearing the Disabled Body, a study of how poor posture became a dreaded pathology in twentieth century United States, is forthcoming from Princeton University Press. You can learn more on Linker’s website or find her on Twitter as @BethLinker

Header image: Children of posture class Red Cross Child Health Station #2 Greenwich House, 27 Barrow Street, New York County Chapter, American Red Cross, in incorrect standing position, before instruction in posture, 1921. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Collection.

Interesting how even here ableism and racism intersect. I would like to know more about how this straight back craze affected Black Americans, with people of African descent often being more curvy than white Americans.