Disability history often neglects one of the largest demographics of disabled people: the elderly. According to the United Nations, over 46 per cent of people aged 60 and over have disabilities, and the numbers were likely not much different historically (United Nations Department of Social and Economic Affairs, n.d.). Yet the experiences of these elderly people do not align neatly with the traditional paradigms of disability history. Elderly people are – and were – beyond reproductive age, so they were no longer targets for eugenic sterilization. With their education and working years behind them, efforts to access schools and universities or pressure to conform to the productive exigencies of the labour force were not major factors in their lives. Although there are some activist histories to explore – such as the story of the Grey Panthers, founded in 1970 – historically, many elderly people experienced disabilities only late in their lives, hampering any efforts at organization and protest. With the continued proliferation of nursing homes and long-term care facilities, especially for people experiencing dementia, elderly people with disabilities also upend the conventional twentieth-century historical trajectory of deinstitutionalization.

With its focus on the experiences of disabled people and the politics of stigma, exclusion, and institutionalization, disability history and its tools should be put at the center of the history of aging, and aging at the center of disability history. My research examines the history of Rosehaven Home, which opened in December 1947 in Camrose, Alberta, about an hour’s drive southeast of Edmonton. This hospital, which operated under provincial government control until 1992, is little-known, but its story invites important questions about how we might approach the intersecting histories of institutionalization, psychiatric disability, and aging. When it opened, Rosehaven was unique in Canada. It was explicitly a psychiatric facility that operated under the remit of Alberta’s Division of Mental Health, yet it was reserved for a particular demographic – people over the age of seventy. Rosehaven was so novel that it even earned a special achievement award from the American Psychiatric Association in 1950.

As an institution purporting to care for aged people with disabilities, Rosehaven encapsulated the period’s ideas of what we might term “eugerics” and “eugeric institutions.” If “eugenics” refers to the perverse science of “good breeding,” swapping in a derivative of the Greek word “geron” (meaning old or aged person) invites us to examine how ideas about “good aging” shaped life for disabled elderly people. What imaginaries, assumptions, and concepts underpinned institutions and policies that were ostensibly meant to help aged people with disabilities live well? And did the ideals of good aging meet with liberatory – or discriminatory – realities?

Despite initial fanfare when it opened, Rosehaven was soon at the periphery of Alberta’s psychiatric hospital system. Its residents straddled two marginalized demographics – elderly people and people with mental illness – and official reports gave the facility only brief attention. On rare occasions when Rosehaven made the news, reporters described its residents in varied terms – some euphemistic and some reflecting a kind of ontological uncertainty about who lived in the hospital in the first place. An article in Within Our Borders, a Government of Alberta newsletter, described Rosehaven as a place for “senile mental patients” (Within Our Borders 1959). In 1969, a report on Alberta’s mental hospitals termed Rosehaven a “special kind of nursing home for ‘burned-out’ psychotics” (Blair 1969, 51). Perhaps trying to avoid provoking stigma and backlash, the Camrose Canadian left out the hospital’s affiliation with psychiatric care entirely, referring to it as a “home for certain classes of aged patients” and an “institution where patients over the pensionable age could be given the care they required” (Camrose Canadian 1947).

Rosehaven’s superintendent called the residents “patients whose faculties are impaired in one way or another due to their age,” though this was not entirely true (Camrose Canadian 1947). Data from 1957 indicates that only a little over a third of Rosehaven’s patients had entered institutional care because of a diagnosis of Senile Psychosis (Government of Alberta 1959, 126). The majority of Rosehaven’s residents had first been institutionalized in one of Alberta’s other mental hospitals – sometimes for decades – because of some other psychiatric condition. Indeed, an article in The Organized Farmer noted that Rosehaven “is designed for persons who do not require active treatment in a mental hospital but have been in one” (Farmers Union of Alberta 1959).

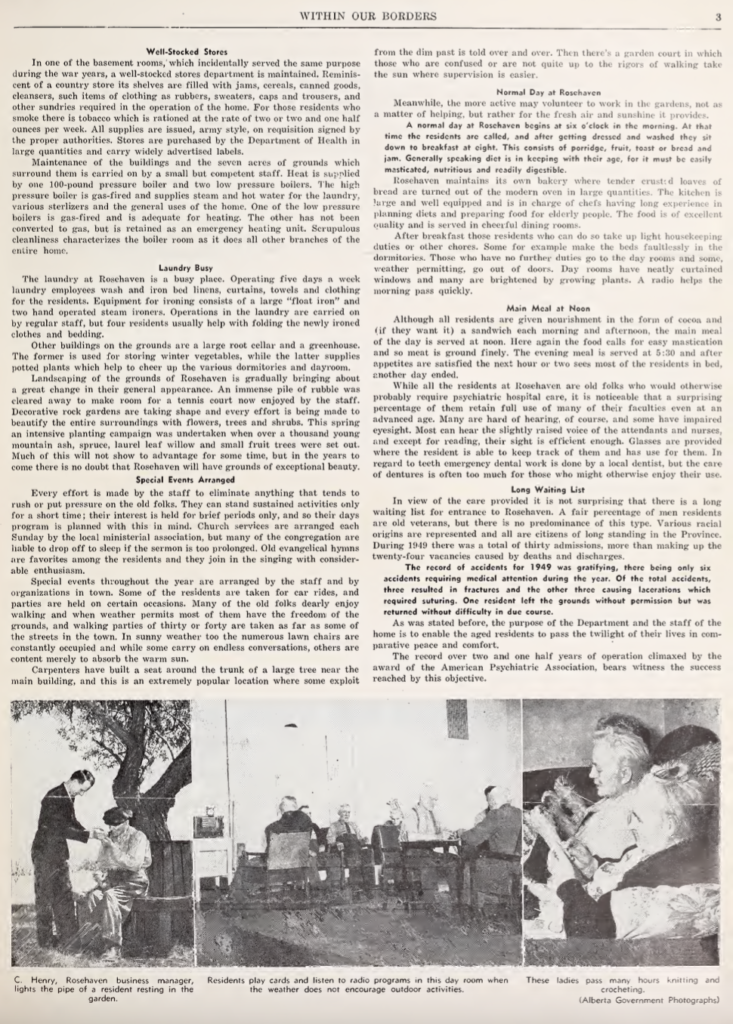

What these different descriptions shared was a belief that Rosehaven’s residents needed only custodial care, since their age presumably foreclosed any hopes for recovery and independence. Though the archive suggests that many of the staff were attentive and compassionate, Rosehaven was a space for biding time. It existed to make room in Alberta’s acute care psychiatric facilities for younger patients who still held some hope for cure. There was no electroshock or other therapeutics at Rosehaven, though there were ample amounts of barbiturates, painkillers, antipsychotics, and antidepressants. As late as 1969, it had no occupational therapists on staff. The government newsletter Within Our Borders presented this as a kind of eugeric decision, arguing that elderly people’s short attention spans were ill-suited to the kinds of tasks that characterized occupational therapy in the first place (Within Our Borders 1950, 2).

As a eugeric facility, Rosehaven was instead meant to accommodate the “natural” slowness of the elderly body and mind. One newspaper article referred to the institution’s culture as an adjustment to the “dilatory habits of old age” (Western Farm Leader 1953). The chronos of linear time dissolved into a kind of kairos – a Greek term that specifically refers not to the quantitative time that ticks past, but rather to a qualitative form of time. Rosehaven was supposed to provide the “right kind” of time for the aged. As described in Within Our Borders, “[d]uties are light, and time is abundant.” The newsletter went on, “there may be a game of checkers or solitaire to pick up from yesterday. But if these important activities are not finished today there is always tomorrow” (Within Our Borders 1950, 2). Unlike the anxious futurity of eugenics, which pressed to secure sterilization in time to avoid a polluted future, eugerics seemed to step outside chronological time entirely. Eugeric institutions like Rosehaven were evidently unconcerned with the possibility of boredom, loneliness, or purposelessness, and instead committed to an ideal of supposedly endless, empty hours of de-personalized comfort and calm for the residents’ final, futureless years.

Close attention to the archive, however, shows that this was only an ideal – and not entirely the reality. The staff actually depended on the residents to help with many tasks. These included things such as setting up the facility when it first opened and helping to make beds, prepare food, and tend the grounds. Annual reports listed this work as “occupational therapy,” but there was little discussion of its therapeutic value or how it might be expanded into a more comprehensive program under professional supervision. The ideal of “good aging,” then, clashed with eugeric reality. Even as the disabled elderly were supposed to exist in a state of dilatory leisure, the institutions that housed them were chronically underfunded and relied on their labor.

Like eugenics, eugerics was an ostensibly positive program that was unable to transcend and was ultimately defined by the forces of prejudice, neglect, and exploitation. In the absence of family support or a well-developed system of publicly funded nursing homes, the psychiatric hospital system served as the last, inadequate social safety net for elderly people with disabilities. One report from 1962 pointed out that some 400 “senile patients” were languishing in Alberta’s acute care psychiatric hospitals at Ponoka and Oliver. Ideally, they should have been transferred to a facility like Rosehaven, but there was simply no room for them (Brief for the Royal Commission, 1962, 5). When the province tried to transfer residents to nursing homes during the deinstitutionalization of the late 1960s and 1970s, some homes refused to take people who had been in psychiatric facilities (Edmonton Journal 1970). Though Rosehaven’s population indeed decreased from a high of over 500 residents in the early 1960s to less than 300 in the early 1980s, the facility remained as a last resort for people whose geropsychiatric conditions could not be accommodated elsewhere. Even after Rosehaven was transferred to a non-profit organization, The Bethany Group, in 1992, it continued to specialize in caring for seniors with “difficult to manage” behaviours (Bethany Group n.d.).

Despite the enthusiastic attention it received when it opened, Rosehaven was fundamentally reactive. It existed to gather up those left behind by the failure of other systems of cure or care. A “eugerics” framework recenters the stories of Rosehaven’s residents and helps to untangle the ideals and realities that animated the last years of their lives, as well as the lives of so many other disabled elderly people.

Thank you to AMS Healthcare for their support of this research.

References

American Psychiatric Association. 1950. “Mental Hospital Award Winners Announced.” American Psychiatric Association Mental Hospital Service Bulletin 1, no. 5.

Government of Alberta. 1959. Annual Report of the Department of Public Health, Province of Alberta, 1957. https://archive.org/details/ableg_33398004131487/page/126/mode/2up?q=rosehaven

Blair, W.R.N. 1969. Mental Health in Alberta. Edmonton: Human Resources Research and Development Executive Council – Government of Alberta.

Brief for the Royal Commission on Alberta’s Mental Health Services, January 1962. Provincial Archives of Alberta, 75.608, folder 27.

Camrose Canadian. “Official Opening of ‘Rosehaven’ in Sept.” August 20, 1947.

Edmonton Journal. “Community health nurses are helping to keep patients out of hospital through regular home visits.” June 17, 1970.

Farmers Union of Alberta. 1959. “F.W.U.A. Hi-Lites.” Organized Farmer 18, no. 7 (July): 23. https://archive.org/details/N022311/page/22/mode/2up?q=rosehaven.

The Bethany Group. n.d. “Rosehaven Provincial Program and Education Services.” Accessed March 11, 2024. https://www.thebethanygroup.ca/rosehaven-provincial-program#in-house-program

United Nations Department of Social and Economic Affairs. n.d. “Ageing and disability.” Accessed March 11, 2024. https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/disability-and-ageing.html.

Western Farm Leader. “View of the Rosehaven Residence.” May 15, 1953. http://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers/WFL/1953/05/15/9/.

Within Our Borders. “Camrose Rosehaven Home.” July 15, 1950.

Within Our Borders. “Splendidly Equipped and Staffed Hospitals Economically Care for Mentally Ill Albertans.” May 11, 1959.

Caroline Lieffers is an Assistant Professor of History, specializing in nineteenth and twentieth-century social and cultural history, at King’s University, Edmonton. Her research examines the relationship between disability and U.S. imperialism, and she also writes about the histories of food, travel, and childhood.