The right for disabled people to access creative works on equal terms seems like an uncontroversial proposition. But it is also one that has historically led to moral panics over government funding of accessibility when politicians center accessibility of controversial content in broader culture wars.

Thirty years after its passage, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) stands as the flagship disability rights law in the United States. But one underappreciated shortcoming of the ADA is that it does not typically regulate publishers or authors of creative works or require them to create and distribute accessible versions of their works.

From the mid-nineteenth century to the end of the twentieth century, the accessibility of creative works was instead typically facilitated by specialized institutions dedicated to remediating books and movies in accessible formats with the help of government funding. One consequence of the government funding of accessible creative works has been the propensity of (typically conservative) lawmakers to start moral panics about the use of government funding to disseminate objectionable content.

This essay presents two case studies on how instances of moral panic have challenged accessibility for disabled people: access to controversial Braille versions of popular magazines for blind or visually impaired people, and decisions about which television programs should be captioned for people who are deaf or hard of hearing.

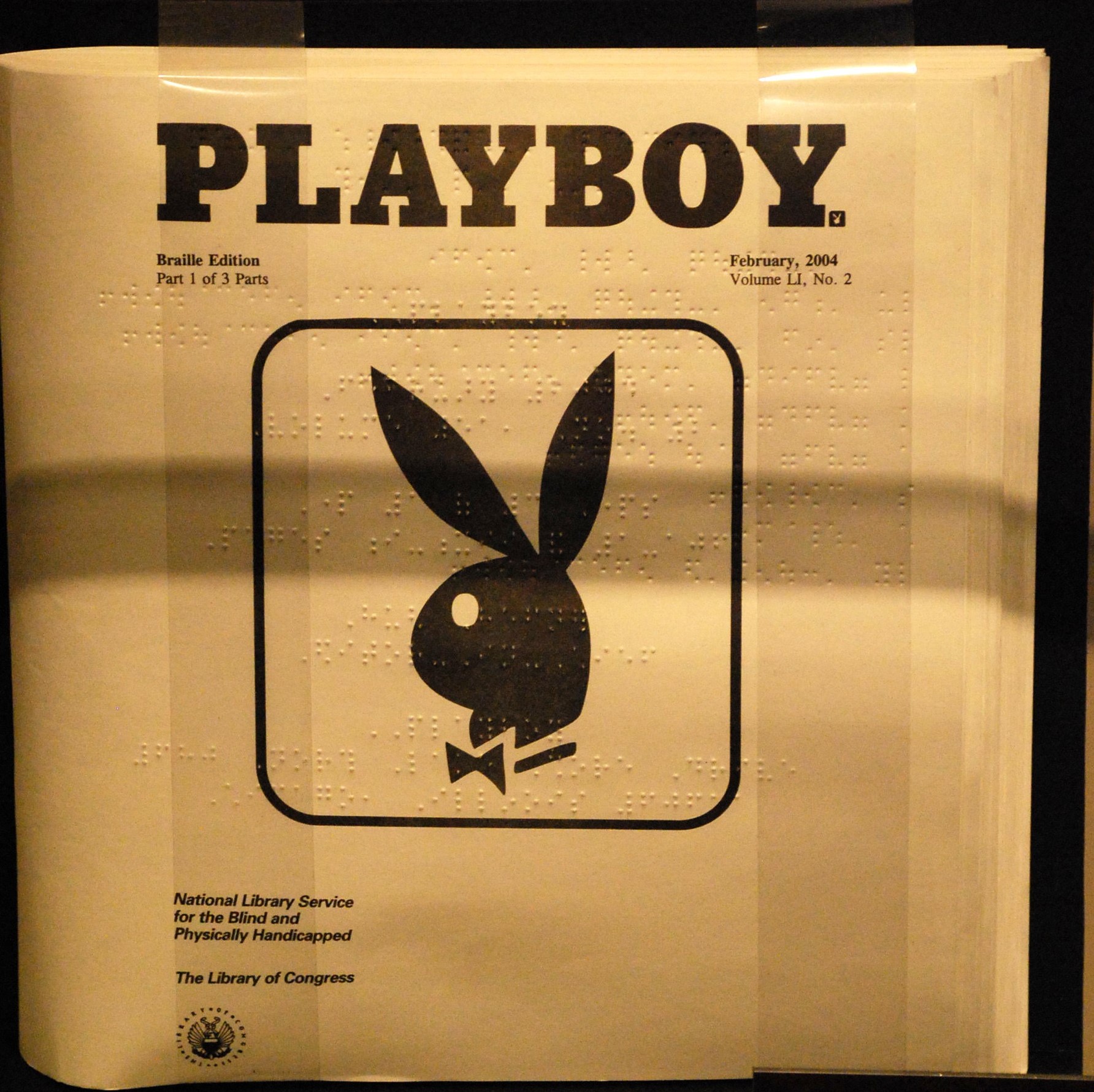

The National Library Service for the Blind and Print Disabled and the Moral Panic over Braille Playboy

In the 1860s, the first notable national efforts to produce tactile books for people who were blind took place at the American Printing House for the Blind (APH) in Louisville, Kentucky.1 Nearly seventy years later, Congress extended these efforts under the Pratt-Smoot Act2 by appropriating funding to the Library of Congress to begin providing books in accessible formats.3 Under this Act, the Library would provide the books to readers who were blind or print disabled through a program now known as the National Library Service for the Blind and Print Disabled (NLSBPD). This program expanded several times from the 1930s through the 1960s to better service readers.4

The NLSBPD ran into controversy in the 1980s when Republican Congressmen sought to preclude the NLSBPD from distributing braille versions of Playboy.5 Along with Good Housekeeping, National Geographic, and a few dozen other publications, readers who were blind or print disabled could check out or receive at home a black and brown edition of Playboy with no pictures—just the articles—embossed in Braille. Playboy had been recommended for inclusion in the NLSBPD’s distribution program by an advisory committee with representatives of readers, libraries, and disability rights organizations.

From 1973 until 1985, Playboy was one of the most popular magazines distributed by the NLSBPD.6

In 1981, Representative Chalmers Wylie demanded that Daniel J. Boorstin, the Librarian of Congress, stop the production and distribution of Playboy in Braille. After Boorstin defended the practice on the grounds of Playboy’s widespread popularity, Rep. Wylie introduced a bill that would reduce the NLSBPD’s appropriation by just enough to put a stop to the Braille version of Playboy, noting that he did

“not think the public should be left with the impression that the Federal Government sanctions the promotion of sex-oriented magazines such as Playboy.“7

Wylie told the Washington Post that “Playboy assails traditional moral values and . . . that promoting the reading of Playboy in this way does lead to undesirable activities.”8

After the bill passed, Boorstein relented, canceling the production of Braille Playboy but accusing Congress of censorship. The American Council of the Blind (ACB) was inundated by letters from blind readers complaining of censorship, such as this one:

“Since Playboy has always been a defender of the First Amendment, I am not sitting idly waiting for my monthly copy of Playboy. What gives you the moral authority to govern my choice of reading material when it’s obviously illegal to make that choice for my sighted counterparts?”

A coalition of disability rights and library organizations and members of Congress led by ACB and the American Library Association sued Boorstein, alleging that removing Playboy from the NLSBPD program violated their constitutional rights and demanding its reinstatement.9 The D.C. District Court agreed, ruling that the decision to remove Playboy from the program was a content-based policy that violated the First Amendment.10 Playboy remains available for lending from the NLSBPD to this day, sitting in the catalogue between Popular Mechanics and the Piano Technicians Journal.11

The Department of Education and the Moral Panic over Captions for Baywatch and Jerry Springer

Following the introduction of “talkie” movies with soundtracks in the 1930s, efforts evolved to develop captioned films to restore access to deaf and hard of hearing viewers. In the 1950s, efforts by the non-profit organization Captions Films for the Deaf (CFD) developed some of the necessary technological infrastructure to create and distribute captioned programming.12 But budget constraints limited CFD’s efforts, and the organization turned to the federal government for help.13

In 1958, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed into law the Closed Caption Loan Service of Films Act. Structured similarly to the Pratt-Smoot Act, the Act required the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) (the predecessor of the modern Department of Health and Human Services), and later the Department of Education, to establish a parallel program to the National Library Services to provide a lending service for captioned films.14 In 1979, Congress passed an expansion to HEW’s funding to authorize the captioning of television programming.15 A year later, the first closed-captioned television broadcasts appeared.16 While Federal Communications Commission (FCC) rules under the Telecommunications Act of 199617 ultimately mandated that most television programming be captioned,18 the long phase-in of the FCC’s rules necessitated a continued role for the government to fund captioning for television programming.

A new moral panic descended when Congressmen took umbrage at the provision of federal funding to caption the beach drama Baywatch.19 A news release from the House Committee on Economic and Educational Opportunities contained an entry stating “Number of Department of Education programs to pay for closed captioning of the television show ‘Baywatch’: 1,” an expenditure that led to a Republican investigation of the Department’s budget, linking Baywatch captioning to other expenditures they objected, such as a safe-sex demonstration involving a students licking a condom and making an “orgasm face.”20 A committee spokesperson exclaimed that “[i]t’s amazing, once you start digging, what you’ll find.”21 Judy Heumann, the assistant secretary for special education and rehabilitative services retorted that “[w]e don’t believe in censorship.” The panic over Baywatch led to legislation that set limited future funding of captioning services by the Department of Education to only “educational, news, and informational” programming.22

Shortly after the Baywatch fracas, further debate erupted over the Department of Education’s funding of captioning for episodes of the Jerry Springer Show.

In a letter to Secretary of Education Richard Riley, Senators Joe Lieberman and Dan Coats complained “The Jerry Springer Show . . . is the closest thing to pornography on broadcast television” and that “[t]he mission of the Department’s program is not to expose the hearing-impaired to every form of cultural depravity under the sun.”23 Department of Education spokeswoman Julie Green retorted that “[t]he purpose of the [funding] program is to help people who are deaf watch programs” of their choice and “[i]t’s not our role to censor programs that are available to the general population.”24 Following protests from the National Association of the Deaf and its members,”25 Education Secretary Richard Riley rejected the Senators’ request, refusing to

“supersede the individual judgment of millions of Americans who have worked long and hard to make sure that they have full standing as citizens in this society.”26

Nevertheless, the moral panic over caption funding culminated in the George W. Bush administration organizing a five-member panel, formed without public input or explanation, to create a list of television shows that could not receive federal captioning grants from the Department of education,27 all under the auspices of determining which shows were “educational, news, and informational.”28 The list apparently disallowed funding for captions of a wide variety of children’s, sports, documentary, and even prime-time programming out of concerns over depictions of violence and other objectionable content. While the list never became permanent as a result of widespread opposition from deaf advocates, its impact was also muted by the fact that the programs would begin to become covered by the FCC’s captioning mandates.

An Unavoidable Risk

These examples illustrate the moral panics are an unavoidable risk when disability rights depend on government funding of accessibility. While the Braille Playboy saga illustrates how the First Amendment can help protect the rights of disabled people to avoid content-based discrimination by government agencies, vesting agencies with discretion to decide which creative works will be made available in accessible formats leaves open the possibility of censorship efforts by politicians willing to grandstand over the use of government funding to disseminate objectionable content.

The risk of moral panics, then, underscores the importance of making all creative works in a medium accessible. For example, the transition from the Department of Education’s grant funding model to the FCC’s regulations requiring programming providers and distributors to caption a much wider range of television programming has made it much harder for politicians to raise moral objections to captioning particular programs—because all programming (subject to categorical exemptions that are largely rooted in concerns about economic burden) must be captioned. These models of ubiquitous accessibility, which center responsibility for accessibility with the content’s own creators and distributors instead of government institutions, can significantly limit the of moralistic objections to accessibility and should form the basis for future disability rights law and accessibility policy.

Blake Reid studies, teaches, and practices at the intersection of law, policy, and technology. He serves as a Clinical Professor at Colorado Law, where he serves as the Director of the Samuelson-Glushko Technology Law & Policy Clinic (TLPC) and as the Faculty Director of the Telecom and Platforms Initiative at the Silicon Flatirons Center. Before joining the faculty at Colorado Law, he was a staff attorney and graduate fellow in First Amendment and media law at the Institute for Public Representation at Georgetown Law and a law clerk for Justice Nancy E. Rice on the Colorado Supreme Court. For more information, see https://blakereid.org.

Header: Adam Fagen, Playboy in braille. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) license.

Notes

- Carol B. Tobe, “Embossed Printing in the United States,” in Judith M. Dixon (ed.), Braille into the Next Millennium (2000).

- The Act was named after its sponsors, Rep. Ruth Pratt and Sen. Reed Smoot. See generally Laws and Regulations, National Library Service for the Blind and Print Disabled, Library of Congress.

- An Act to provide books for the adult blind, 46 Stat. 1487.

- See 36 C.F.R. § 701.6(a).

- Jessica Lipsky, “For years there was a Playboy for blind people, then a Republican congressman tried to kill it,” Timeline (Sep. 21, 2017).

- Am. Council of the Blind v. Boorstin, 644 F. Supp. 811, 813 (D.D.C. 1986)

- Id. (citing 131 Cong. Rec. H5932 (July 18, 1985)).

- Amber Phillips, “That time Congress fought over printing Playboy in Braille,” Washington Post (June 12, 2015).

- Boorstin, 644 F. Supp. at 812-13.

- Id. at 816.

- “Magazines in Special Media,”National Library Service for the Blind and Print Disabled (describing Playboy as “Fiction, interviews, and articles with a male perspective.”).

- Edmund Burke Boatner, “Captioned Films for the Deaf,” American Annals of the Deaf 126 (YEAR), 520-521.

- Boatner, “Captioned Films for the Deaf,” 523.

- “An Act To provide in the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare for a loan service of captioned films for the deaf.” Public Law number 85-905, 72 Stat. 1742 (September 2, 1958).

- Karen Peltz Strauss, A New Civil Right: Telecommunications Equality for Deaf and Hard of Hearing Americans (Gallaudet University Press, 2006), 210.(A New Civil Right at 210 (2006).

- Strauss, A New Civil Right, 211.

- P.L. No. 104-104, 1996 Stat. 652 § 305 (Feb. 8, 1996) (codified at 47 U.S.C. § 613).

- See generally 47 C.F.R. § 79.1; Closed Captioning and Video Description of Video Programming, 13 FCC Rcd. 3272 (Aug. 22, 1997) (subsequent history omitted).

- Strauss, A New Civil Right, 266.

- Mark Pitsch, Federal File: Fedwatch?, Education Week (Apr. 3, 1996), https://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/1996/04/03/28fedfil.h15.html.

- Pitsch, Federal File

- Strauss, A New Civil Right, 266; “Individuals With Disabilities Education Act amendments for 1997,” PL 105–17, June 4, 1997, 111 Stat 37.

- John Carmody, “Jerry Springer in Closed Captions? That’s Not What These Senators Want to Pay for,” Washington Post (Mar. 4, 1998).

- Carmody, “Jerry Springer.”

- Strauss, A New Civil Right, 67.

- Strauss, A New Civil Right, 67.

- Strauss, A New Civil Right, 268.

- Gary Robson, Censorship and Captioning, NCRA.