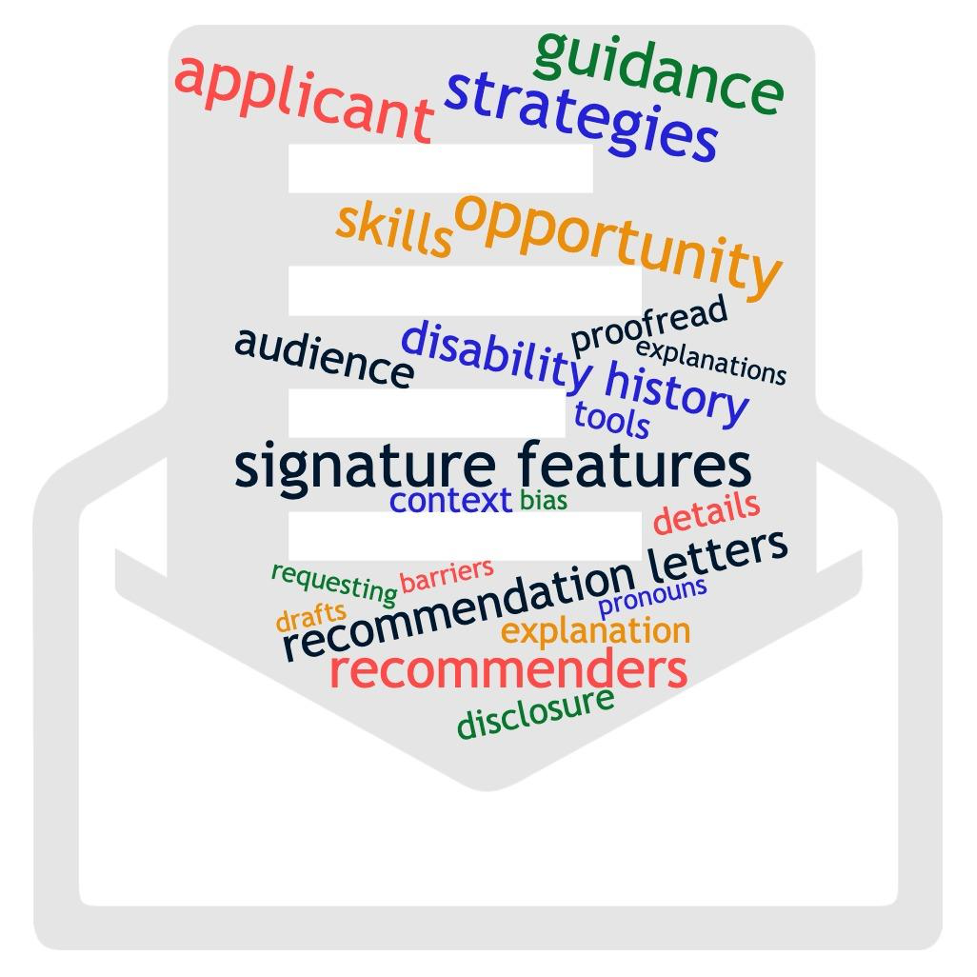

None of us were born with knowledge regarding letters of recommendation. Yet, these are resources that most of us need to use. Long experience requesting and writing recommendations, and the insights gained from successes and mistakes, shape the suggestions that follow. We hope this shared knowledge reduces barriers and creates opportunities.

For information about requesting recommendations, go to Section One.

For information about writing recommendations, go to Section Two.

Section One: Requesting Recommendations

First and foremost, don’t feel guilty about asking others to write recommendation letters for you. This is a standard feature of the disability history profession.

Second, think about letters of recommendation as one interlocking part of a whole portfolio. Cover letters, personal statements, and letters of recommendation—as just three common application features–– can satisfy different purposes in service of the larger goal.

Whom should you ask to endorse your application? There isn’t a simple or universal answer to this question. We found the following factors useful in the selection process:

- Recommendation letter writers need to be experts (broadly conceived)–they must be able to explain your field and your place in it. This can include, for example, providing an explanation of your professional trajectory, relevant technical concepts, your research methods, signature features of disability history, and/or the state of your particular field of study.

- Someone who can speak with specificity about your work may be more helpful than a Big Name In The Field who may not know your work very well.

- Consider the priorities of the institution or organization to which you are applying. How likely would they recognize this potential recommender as a credible source?

How do you know if someone is a good recommendation writer?

- Talk with a trusted mentor about possible letter writers.

- Select someone who shares your intellectual values and priorities.

- Ask the writer to share the letter with you. Recommenders are not required to do so, but some are happy to engage you in the process.

Evaluate how the recommender responds to your requests. It’s a good indication (but not a guarantee of effectiveness) if they are positive about you and about writing the letter. A reluctant or irritated response doesn’t necessarily translate to an ineffective letter, but it may be worth revisiting the criteria by which you’re selecting writers. Ultimately, is this someone in whom you have confidence to endorse your application?

What information should you give a recommender?

- Clear deadlines and details about the job/grant/opportunity.

- An explanation of what draws you to the opportunity.

- The pronouns you want them to use when referencing you.

- The name(s) you want them to use when referencing you (i.e. your legal name, a nickname rather than a formal first name etc.).

- When relevant, a CV or outline of academic, professional, and related experiences.

- Draft of cover letter, dissertation abstract, or related writing.

As a general rule, the more specific guidance you give to a recommender, the more tailored their letter can be. You can assist the recommender by identifying:

- What you’d like the recommender to foreground, explain in detail, and/or contextualize. This might include what distinguishes your work, why you’re qualified for the opportunity, or how the opportunity connects to future plans. You might ask recommenders to spotlight relevant skills or experiences that aren’t otherwise legible in your other application materials.

- Depending on the job/grant/opportunity, you may want one writer to address teaching and mentoring skills, another to situate your work in one area of study, and a different recommender to connect your work to related fields.

Disclosure

How and whether to disclose a disability and other identity factors is a high stakes decision; there is no single “right” answer and you likely will receive contradictory guidance. We’ve found it beneficial to identify for ourselves what we hope for, fear, and need from recommenders. Finding ways to honor these factors in the approach to a recommender can be empowering; however, these insights do not have to be shared with the recommenders.

Some related things to keep in mind:

- Recommenders may be used to strategically disclose information that you might not want to name directly in your application, such as a disability, a partner, a pregnancy, and/or gaps in your professional record.

- Be direct. Make very clear to your recommender what is acceptable for them to mention and what is not.

Section Two: Providing Recommendations

Thoughtful recommendation letters take time and energy, so why should you agree to write them? There are many answers to this question; we’ll offer two: first, it is an opportunity to affirm and advocate for our field; and second, it is a material way to support opportunities for members of our disability history community.

- When you say yes, what then? Ask for:

- Due date(s) for the letters.

- General information and contact information for the job/grant/opportunity.

- The Applicant’s desired pronoun(s).

- The Applicant’s contact information (how best to reach them as needed).

- Any specific foci–such as signature features of their work–that the applicant desires to be addressed.

- Whether there’s anything you should address that the applicant does not want to address themselves (see Disclosure).

Nuts and Bolts: Recommendation Letter Essentials

- This is not about you. Focus on the applicant.

- Explain how you know the applicant, using their desired pronoun(s).

- Use a professional tone and title to refer to the applicant.

- Be specific. Situate the applicant in context: identify your standard of evaluation of the applicant. For example, in X number of years, advising X number of people, and X kind of educational/professional/organization setting.

- Know your audience. For example, don’t assume that everyone will know what ableism means. Explain technical terms.

- Explain what is original, distinctive, and/or important about the applicant’s scholarly work (or other focal point of the opportunity, such as teaching or community organizing).

- Detail the skillsets of the applicant: what research, linguistic, collaborative, pedagogical, and/or technological talents does this person possess? Use specific examples to illustrate.

- Consider noting applicant’s demonstrable and commendable related skills, such as reliability or being collaborative.

- Tailor your letter to the specific job posting/grant/opportunity, indicating how the applicant meets the goals and requirements of the position.

- Only disclose the personal circumstances of the applicant if they have given permission and/or asked you to do so.

- Proofread carefully for gender, racial, ethnic, and/or disability bias. Do not assess personality.

- Submit the letter on time. There is no need to add further stress to the lives of applicants.

When to say “no”…

Sometimes, it isn’t possible or appropriate to write recommendation letters. This can include–but isn’t limited to–inadequate advance notice to write a good letter, an inability to credibly endorse the individual’s application, and conflicts of interest. Accounting for these and other possibilities, some practices that can be helpful include:

- Establishing and making available your personal policies for recommendation letters, including how much advance notice you typically need. (This practice models clarity and supports sustainability and accountability.)

- Suggesting other credible recommenders, or offering to brainstorm potential recommenders with the applicant.

- If appropriate, encourage applicants to consult with resources at their institution, such as Centers for Research and Learning, Writing Centers, or Centers for Careers and Internships.

No one likes rejection, but offering constructive feedback can contribute positively to an applicant’s professional development. Modeling integrity in this context matters: claiming time constraints when declining one person’s request while accepting someone else’s, for instance, may harm relations and professional status.

Cultivating the skills of requesting letters of recommendation and writing them unfolds unevenly and over long periods of time. These guideposts are an invitation to longer conversations within our disability history community. Please add, amend, and assess as appropriate to your situation. We hope others will contribute more blogs about this important professional practice.

Further Reading

For more on tips to reduce bias in recommendation letters, see:

Cooke, Michele. 2022. “Writing Reference Letters for People With Disabilities.” Inside Higher Education. February 7, 2022. https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2022/02/08/guidance-writing-references-people-disabilities-opinion.

Kim, Sora and Asmeret Berhe. n.d. “Letters for POC.” Accessed October 2, 2023. https://sora.leekim.org/updates/letters-for-poc.

Dutt, Kuheli. 2019. “Avoid Implicit Gender Bias in Recommendation Letters.” Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, The Earth Institute of Columbia University. Accessed October 2, 2023. https://diversity.ldeo.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/content/Avoid%20gender%20bias%20letters%20Dutt%202019.pdf.

Emory University School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. n.d. “Anti-Racism Action Guide: Reducing Bias in Recommendation Letters, Candidate Evaluations and Assessments of Academic Products.” Accessed October 2, 2023. https://med.emory.edu/departments/psychiatry/_documents/_documents1/avoid_bias_workplace.pdf.

Advance Center for Women STEM Faculty, Lehigh University. n.d. “Best Practices for Reading and Writing Letters of Recommendation.” Accessed October 2, 2023. https://advance.cc.lehigh.edu/sites/advance.cc.lehigh.edu/files/Letters%20of%20Recommendation%20One%20pager.pdf

For more reflections on disability and intersectional disclosure, see:

Kerschbaum, Stephanie L., Laura T. Eisenman, and James M. Jones, eds. 2017. Negotiating Disability: Disclosure and Higher Education. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.9426902.

Pearson, Holly and Lisa Boskovich. “Problematizing Disability Disclosure in Higher Education.” Disability Studies Quarterly 39, no. 1 (Winter 2019). https://dsq-sds.org/article/view/6001/5187.

Kim E. Nielsen is Distinguished Professor of Disability Studies and History at the University of Toledo (Ohio). Her scholarship explores gender, disability, law, and citizenship throughout history. She is author of the widely used A Disability History of the United States and co-editor of the twice award-winning Oxford Handbook of Disability History. In addition, she served as founding president of the Disability History Association and co-edits the Disability Histories book series at the University of Illinois Press. Furthermore, Professor Nielsen has expertise regarding Helen Keller, Anne Sullivan Macy, and biography. She is author of The Radical Lives of Helen Keller, Beyond the Miracle Worker: The Remarkable Life of Anne Sullivan Macy and Her Extraordinary Friendship with Helen Keller; and edited Helen Keller: Selected Writings. From 2015-2018, Nielsen co-edited the journal Disability Studies Quarterly. Nielsen’s most recent book, Money, Marriage, and Madness: The Life of Anna Ott, analyzes a mid-19th century physician institutionalized for two decades at a Wisconsin insane asylum. She speaks frequently and around the globe on issues of disability and history. She received her Ph.D. in History from the University of Iowa.

Susan Burch is a Professor of American Studies at Middlebury College. Her research and teaching interests focus on histories of deaf, disability, Mad, race, ethnicity, Indigeneity, and gender and sexuality. Burch is the author of Signs of Resistance: American Deaf Cultural History, 1900 to 1942 (2002) and a coauthor, with Hannah Joyner, of Unspeakable: The Story of Junius Wilson (2007). She has coedited anthologies including Women and Deafness: Double Visions (2006), Deaf and Disability Studies: Interdisciplinary Perspectives (2010), and Disability Histories (2014), and also served as editor-in-chief of The Encyclopedia of American Disability History (2009). Her latest book, which has recently received the National Women’s Studies Association Alison Piepmeier Book Prize, and the Disability History Association’s Outstanding Book of 2022, Committed: Native Families, Institutionalization, and Remembering (University of North Carolina Press, 2021) centers on peoples’ lived experiences inside and outside the Canton Asylum, a federal psychiatric institution created specifically to detain American Indians. She earned her BA degree in history and Soviet Studies from Colorado College and her MA and PhD in American and Soviet history from Georgetown University.