On the 28th of October, 1673, physicians working at the official medical department of the early modern Russian Empire, the Apothecary Chancery, examined a wounded soldier and gave this assessment:

“Shot by a musket into his Semyon’s right leg around the secret strings [groin], it is not possible to treat this wound, as if we were to begin the treatment, that would lead to his death, and he Semyon is infirm and decrepit, and it is not possible for him to serve the Tsar.”[1]

Semyon’s case was one of many. Wounded soldiers were routinely assessed by the Apothecary Chancery during the seventeenth century. These records are not personal reminiscences of pain, but official records of wounded servitors, noting the cause of the wound, its location and nature, its treatability, and the possibility of the soldier returning to duty. One aspect is notably missing from these documents: an explicit acknowledgement of pain. What, then, can we do with historical documents that explicitly discuss physical trauma but not pain?

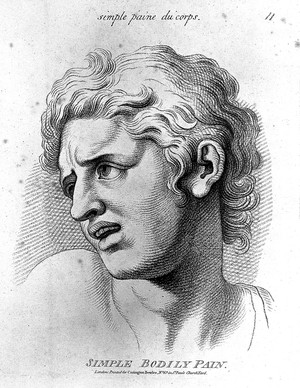

In her classic The Body In Pain, Elaine Scarry claimed that pain is ultimately inexpressible, a concept that has proven both hugely influential and deeply controversial.[2] Especially interesting are the reactions of a new generation of disability scholar-activists, who have responded with academic and creative works that seek precisely to express and understand the pain Scarry declared so fundamentally incommunicable. Travis Chi Wing Lau, for instance, has made direct poetic response to this, in Epistle to the Body in Pain.[3]

Debates over the expressibility of pain are relevant to historical documents dealing with physical trauma. Can we find narratives of pain in in the Apothecary Chancery files?

Many studies of pain, such as Elaine Forman Crane’s study of eighteenth-century America, rely heavily on personal reminiscences and first-person accounts.[4]. Such accounts are vital, as they allow us to consider the sufferer’s individual experience and understanding. There are also limits to using such sources. A Muscovite soldier like Semyon, living in a community in which literacy was a practical skill primarily expected of professional scribes, would never have composed a written work expressing his pain. To focus too closely on personal reminiscences would be to write sufferers like Semyon out of the history of pain.

Semyon and his fellow wounded Muscovite soldiers have something important to tell us about pain and its expressions, if we look for that pain in those cold, bureaucratic medical records. One key text is this examination from 1633:

“The wounded Toropets resident Fedor Petrov syn Boranov [reported] that when he was on assignment from Toropets and was in the region of Velizh he was wounded by a pischal [a firearm similar to a rifle] by a through-and-through wound in his right hand and the hand was damaged by the bullet and the middle finger torn off, hanging only by the skin and the veins for all the fingers and damaged and the wound painful.”[5]

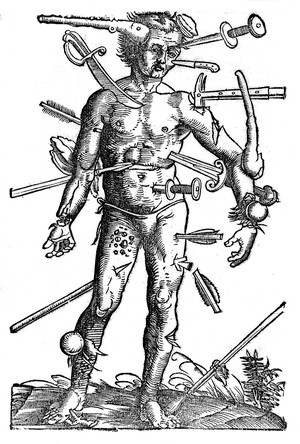

The graphic description of Fedor’s wound is striking. Nearly four centuries after this text was written, I have seen audience members flinch when I present this quote in a talk. Presented with a description of Fedor’s wounds, we feel a distant echo of the pain he felt.

In Fedor’s case, his file contained at least a brief textual acknowledgement that the wound was painful. This is atypical. Other records commonly elide pain:

“And by their examination [in 1674] of Captain Pavel Stepanov Agalin: he Pavel is wounded from a musket in the right shoulder in the shoulder-blade and the shoulder-blade is pierced and the bullet stands in it, and that bullet lowered itself downwards into the bone, and that wound became gangrenous more than a quarter of an arshin [in diameter, around 18 centimetres] and the entrance wound is increasing in size; and he Pavel has the same arm broken apart at the elbow bone, and the right leg shot through below the knee into the black meat [lit.]; and it is not possible for him to serve the Great Lord’s [tsar’s] service because he does not control the right arm and to cure him is not possible because the right arm been reduced to bone.”[6]

Pavel’s injuries are extensive, and one can imagine that they must have been extremely painful. Here, indeed, we must imagine the pain, for unlike in Fedor’s records, the pain itself is not given textual expression. Yet just like with Fedor’s text, audiences often wince in hearing of Pavel’s wounds. We feel the pain the document does not name.

The difference between Pavel’s unexpressed pain and Fedor’s expressed pain is not one of a personal choice of the sufferer. Pavel and Fedor did not write these records; they appear to us as the subject of the text, the passive, examined object of physicians and bureaucrats. The choice to include or exclude pain was then not one of existential relationship of sufferer to pain, but of the motivations of the system in which the sufferer found themselves.

Why did bureaucrats want excruciatingly detailed records of wounds that exclude the bodily accompaniment of pain? We can look here at the questions the text seeks to answer: not, does the patient feel pain?, but, will the servitor be able to serve again? To the bureaucrats, these records were not heart-breaking expressions of physical suffering, but a list of problems to solve in repairing a once-useful tool; these were not bodies that felt, but bodies that failed to function.

These records both relate to Scarry and Lau’s points, and move away from them. The texts deal with pain, whether they acknowledge it or not; our pained responses as readers of these texts show that. Yet the presences and absences of pain in these texts do not relate to the struggles over the expressability of physical pain: the soldiers were not defeated by the difficulties of expressing pain. Rather, the bureaucracy stripped them of their voices of pain, interested only in the functionality of their silenced bodies. It is our reading of these texts, not the writing of them, that restores that pain.

That visceral connection we feel to Pavel and Fedor’s pain is important. Linking historical and contemporary experiences has long been a part of histories of pain. As Crane writes, “If human beings, separated by millennia and miles, share any experience, it is the sensation of pain.”[7]

Connecting to Fedor and Pavel’s pain, then, is a route to understanding contemporary pain differently. In a 2017 article about guns in modern America called ‘What Bullets Do to Bodies’, Jason Fagone wrote: “The gun debate would change in an instant if Americans witnessed the horrors that trauma surgeons confront every day.”[8] These early modern Russian records allow us to witness trauma at a distance. In considering historical bodies in pain, we open up a space to think again about sufferers of pain and trauma in our present-day lives.

This, then, is what these records can tell us about both historical and contemporary pain. Sufferers can sometimes appear to be silent because they have been silenced by a system that does not acknowledge or value their pain. The onus then is not on sufferers to express pain, but on scholars to read pain that has been silenced.

—Clare Griffin is Assistant Professor in the History, Philosophy and Religious Studies Department at Nazarbayev University, Astana, Republic of Kazakhstan. Email: clare.griffin@nu.edu.kz

[1] N. E. Mamonov, Materialy dlia istorii medistiny v Rossii, St Petersburg: M. M. Stasiulevich, 1881, vol. 2, p. 502. All translations are my own.

[2] Scarry, Elaine. The body in pain: The making and unmaking of the world. Oxford University Press, USA, 1987.

[3] http://www.thenewengagement.com/literature/shapeless-skin See also http://travisclau.com/current-projects

[4] Crane, Elaine Forman. “‘I Have Suffer’d Much Today’: The Defining Force of Pain in Early America.” Through a Glass Darkly: Reflections on Personal Identity in Early America (1997): 370-403.

[5] Mamonov, Materialy, vol. 1, p. 37.

[6] Mamonov, Materialy, vol. 2, pp. 505.

[7] Crane, Elaine Forman. “‘I Have Suffer’d Much Today’: The Defining Force of Pain in Early America.” Through a Glass Darkly: Reflections on Personal Identity in Early America (1997): 370-403 , see p. 370.

[8] Jason Fagone, “What Bullets Do To Bodies”, Highline, 26th April 2017 URL: https://highline.huffingtonpost.com/articles/en/gun-violence/