As the Great War came to a close in 1918, millions of soldiers began to return home to their families—many looking different than when they first enlisted. For the first time, advances in medical treatments and sanitation allowed men to survive injuries sustained on the front that would have killed them in previous wars. Soldiers who had faced the horrors of the battlefront now returned with missing limbs, suffering from shell shock, and struggling with a range of other disabling issues. In America alone, over 200,000 of the 1.3 million men that served returned home permanently disabled.[1] As these men tried to cope with their newfound infirmities, the question of how to help them through rehabilitation arose. For many, the answer was hydrotherapy.

Image Source: Wikipedia.

Water therapy has been used in many different forms for thousands of years. “There is no remedial agent the scientific use of which demands so thoroughgoing and practical a knowledge of physiology as does hydrotherapy,” declared famed Dr. John Harvey Kellogg in his 1918 manual on hydrotherapy.[2] Hydrotherapy became essential in the healing process of thousands of veterans—and it continues to be essential to many disabled veterans today. After World War I, it skyrocketed in popularity in Allied nations like the United States and Great Britain. Doctors began familiarizing themselves with hydrotherapy and how it could be used to rehabilitate newly disabled soldiers. Different temperatures, lengths of time, and forms of treatment were recommended, depending on what condition or illness doctors hoped to treat. One popular guide on how to rehabilitate disabled soldiers promoted the use of hydrotherapy for the following: cleansing deep wounds, promoting the healing of wounds, relieving muscular spasms and pain, increasing circulation, and stretching muscles.[3] Doctors began to prescribe baths, steam, and douches as a way to ease returning soldiers’ pain and prepare them for the next step of the rehabilitation process.

Treating Physical Wounds

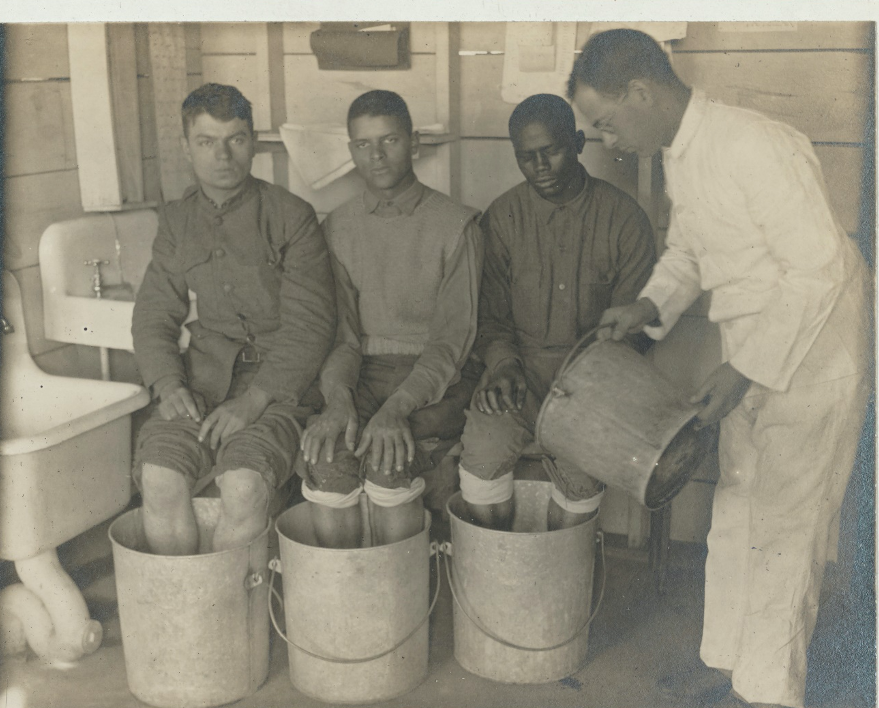

Returning soldiers suffered a wide variety of physical ailments, from gunshot wounds to complex amputations and limb injuries. For many, the epitome of World War I wounds was amputation. The empty sleeve became a permanent reminder of the war; with this reminder came phantom limb pain and the long process of stump healing. Whirlpool baths were most often prescribed to veterans suffering from the aftereffects of amputation. The patient’s arm or leg would be placed into a case of swirling water for approximately twenty minutes, or until the water temperature increased to 115°F. The agitation of the water, when combined with the relatively high temperature used, helped alleviate the nerve pain brought on by amputation: “The pain in the missing hand or foot, so frequently felt after amputation, is rapidly allayed by the whirlpool bath.”[4]

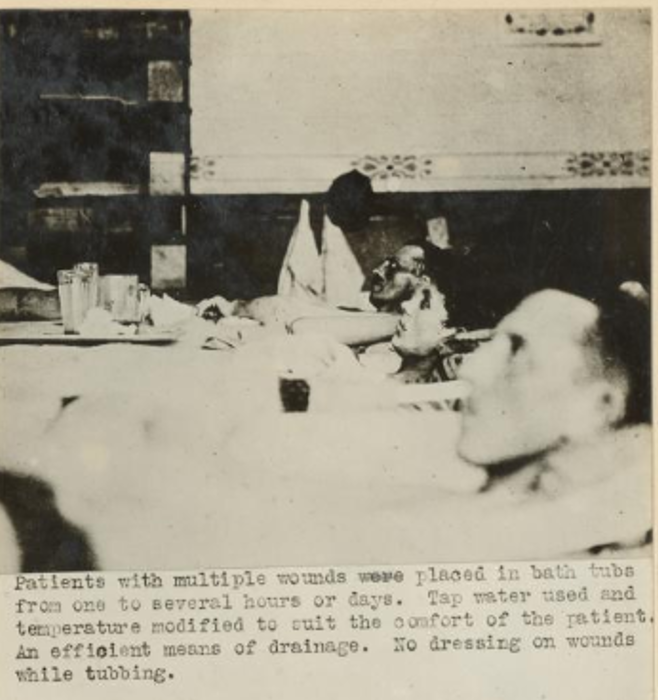

For many other men, infection and gangrene meant a long, stressful recovery once they returned home. Doctors soon found that subthermal baths were a useful therapy for inflamed and septic wounds, burns, and gangrene. These baths were typically kept below 90°F to keep down the temperature of unhealed wounds, relieve pain, and promote discharge. They could also be prolonged for hours or even days until improvements were seen. According to some healthcare providers, long term subthermal baths saved the limbs and lives of many.[5]

Treating Shell Shock

Although physical wounds were a visible reminder of the horrors of war, many men returned with variations of invisible disabilities, including shell shock. The inescapable sights and sounds of war left many men experiencing sudden blindness, deafness, anxiety, and depression. As a result, many doctors discovered that hydrotherapy was an effective treatment for these symptoms. Unlike physical wound treatments, however, hydrotherapy treatments for shell shock were typically combined with massage or electrotherapy.

Baths were perceived to soothe the jangled nerves of those who had experienced trauma at the warfront. Sedative pool baths were also commonly used for those suffering from shell shock. These baths, according to a guide on hydrotherapy for disabled soldiers, were similar to whirlpool baths. Water was constantly flowing through the pool and kept at a fixed temperature of 92 to 94°F. This environment was considered especially helpful for helping the shell-shocked soldier rest and recover. One doctor at the Ontario Hospital at Orpington reported great success in rehabilitating shell shock patients with baths:

“One case admitted to the hospital deaf and mute was quite depressed. We gave him treatment in the continued bath covering a period of nearly two weeks. The patient has recovered hearing and voice. . .and has left the hospital.”[6]

Another doctor in Frankfurt, Germany, recorded his success in curing his patients by continuous immersion in hot baths. In one instance, his patient was treated particularly aggressively; he allegedly stayed submerged in the bath for nearly 40 hours.[7] In most cases, veterans did not require treatment this intense. Nonetheless, healthcare providers found that patients responded well to hydrotherapy for shell shock.

Hydrotherapy Today

Hydrotherapy may not be as popular today as it was after World War I, but it is still used by many for the management of pain and other conditions.[8] Veterans seeking relief from painful physical and mental wounds have sought out hydrotherapy as an alternative form of medicine and have found much success through it. Several treatment centers, for example, have been founded in hopes of assisting recently returned veterans through hydrotherapy. One such center, Wave Academy, reported a 22.2 percent average decrease in PTSD symptoms in clients that successfully completed an eight week treatment course. Other veterans have reported finding increased strength and mobility after participating in pool therapy. Although hydrotherapy can’t fully erase the painful reminders of war—just as it couldn’t in 1918—it can provide relief to veterans looking for an alternative to typically prescribed forms of medicine.

–Jessica Brabble is a second-year history graduate student at Virginia Tech. She is currently researching race, disability, and the use of bodies as spectacle at the North Carolina State Fair at the turn of the twentieth century. You can find her on Twitter @jmbrabbs, or through email: jmbrabble@vt.edu.

Featured image: Men with Septic Wounds were Kept Continuously Immersed in Warm Water at South African Hospital, Richmond Park, London (April 2, 1919). National Archives.

[1] John Kinder, Paying with Their Bodies: American War and the Problem of the Disabled Veteran (Chicago: University of Chicago, 2015), 5.

[2] John Harvey Kellogg, Rational Hydrotherapy: A Manual of the Physiological and Therapeutic Effects of Hydriatic Procedures, and the Technique of Their Application in the Treatment of Disease (Battle Creek: Modern Medicine Pub Co., 1918), 53.

[3] Robert Fortescue Fox, Physical Remedies for Disabled Soldiers (Toronto: MacMillian, 1917), 31

[4] Ibid, 28.

[5] Fox, Physical Remedies for Disabled Soldiers, 32.

[6] Fox, Physical Remedies for Disabled Soldiers, 10-12.

[7] Peter Leese, Shell Shock: Traumatic Neurosis and the British Soldiers of the First World War (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2002), 71.

[8] For further research on the usefulness of hydrotherapy, see A. Mooventhan & L. Nivethitha, “Scientific Evidence-Based Effects of Hydrotherapy on Various Systems of the Body,” North American Journal of Medical Sciences 6 no. 5, 199-209.