I write from the desk of a blind Independent Historian.

We all travel on our own paths. When I decided to return to university to procure a Ph.D. in History, I was in the second half of my life’s century. I was empowered by a personal self-determination and strength to not give up on my desire to complete my degree and still continue my education at a later time in life than most graduate students. When I began my quest to become a historian, I had to learn how to navigate technology that I was not familiar with. My grandchildren are all proficient with the latest information and other computer-based technology, while I had to learn how to navigate my Ph.D. program and accept assistance from a village of readers, librarians, information technology professionals, and campus disability professionals.

I am a mother of four, and grandmother of six. This status gives me a nurturing perspective that I use as a tool to enhance my advocacy for disability scholarship and scholars. It gives me a type of empathy that allows me to think of past, future, and today’s history scholars as my foster grandchildren, who just happen to be interested in disability scholarship and some who happen to be scholars who are disabled persons.

I came to Disability History studies after I had an opportunity to study my first chosen area of history. I initially set my focused study on Western American Plains Peoples’ history and material culture; the area of history I always have loved and continue to investigate. As the completion of my Ph.D. neared, I began attending academic professional history conferences. At these conferences I met diverse groups of disability scholars. These encounters led me to take a turn at the fork in the road, leading to a serendipitous pursuit into disability history and advocacy for disability scholarship.

Disability is a complicated topic to bring into public spaces.

Many people are uncomfortable around persons with diverse disabilities. Historians come from diverse backgrounds and experiences in navigating their education roads. For example, I use the empathy of a grandmother as a tool to understand and advocate for diverse students. I advocate for inclusive accessibility for wheelchair friendly public infrastructure and public transportation, white cane navigation, and American Sign Language (ASL) interpreters for academic conferences. The ability for disabled scholars to integrate into academic professional gatherings with comfort enhances these events for the other diverse scholars in attendance. Unique approaches to discussions and forums on disability history are regularly being introduced at academic gatherings using new technologies that allow this subject to be introduced to a new broader academic audience.

For example, due to challenges brought on by COVID-19, new academic inclusive avenues have broadened how scholarly papers and discussions are shared in academic communities. Academic conferences are expanding audiences by using technology platforms such as Zoom, thus becoming a more inclusive and universal forum for human-to-human contact, no matter our attributes. We can now learn and understand each other in ways that need face-to-face contact, which now is available as internet audio-visual connections. This technology brings many more scholars together from around the globe.

I am proud to be a long-time member of the Western History Association (WHA). WHA has been instrumental in increasing the inclusion of Disability Scholarship and Diverse Scholars who study and write about Disability History into the organization. At this writing, I am still looking forward to participating at the October 2020 WHA Zoom Conference in a roundtable session, “Round Table Discussion on Disability and Equity within History Professions,” that I helped to create. The panel is composed of a diverse group of scholars—undergraduate, graduate, working professionals, and distinguished professors. This is the third session panel on disability in academia that I have coordinated for WHA conferences since 2018.

As an independent historian, I must fund my own paths to academic conferences. Being “independent” has empowered my self-determination to present scholarly papers, attend sessions led by notable scholars, and visit and listen to other scholars about the challenges they have encountered and won. I have participated in new discussions focusing on issues about accessible design, inclusive design, universal design, ableism, and ageism. It is important to network respectful discussions on these topics, while keeping minds open to viable solutions that will improve accessibility to create inclusiveness for all scholars.

I cannot emphasize enough that the discussion about ableism and ageism discrimination in scholarly communities is important. It is a complicated discussion. I advocate recruiting more people with disability challenges and people who study disability history to seek careers in education, public history, and independent research. There are role models out in the academic world. As many others have observed, professors and students with disabilities are not invisible. I am blind, but, I assure you that I am very much seen when I am out and about traveling the world’s museums, archives, libraries, and theaters. Disabled people are academics, politicians, wheelchair dancers on Broadway, and musicians, just to list a fraction of the number of the members in the world of our disabled compatriots.

Finally, let us not forget our pioneering compatriots, who on March, 12, 1990, left their wheelchairs and crawled up the stairs of the nation’s capitol in Washington, D.C. to show that disabled people are not invisible citizens, but rather intelligent and voting citizens able to influence government, laws, education, housing, public transportation, and so much more.

However, the protesters had to make the very obvious point that there were, and still are, many types of barriers challenging persons with disabilities. Journalist William J. Eaton wrote about the Disability Rally, which was organized to highlight to the world the power of disabled persons and their ability to protest for their political and human rights. This significant event is known as the “Capitol Crawl.” Eaton said that the organizers of the disability rights rally came “from 30 states, including many [who were] in wheelchairs, came to demand immediate action on the bill [ADA] without any weakening amendments. At the close of the rally, when dozens left their wheelchairs to crawl to the Capitol entrance, spectators’ attention focused on 8-year-old Jennifer Keelan of Denver, who propelled herself to the top of the steep stone steps using only her knees and elbows.”1

There still is so much to accomplish. Vote! Votes are not invisible. These people were not invisible and because of their tenacity the ADA was passed on July 26, 1990.2 However, the work is not yet done. I will continue to advocate for education and the recruitment of new disability scholars into the history professions.

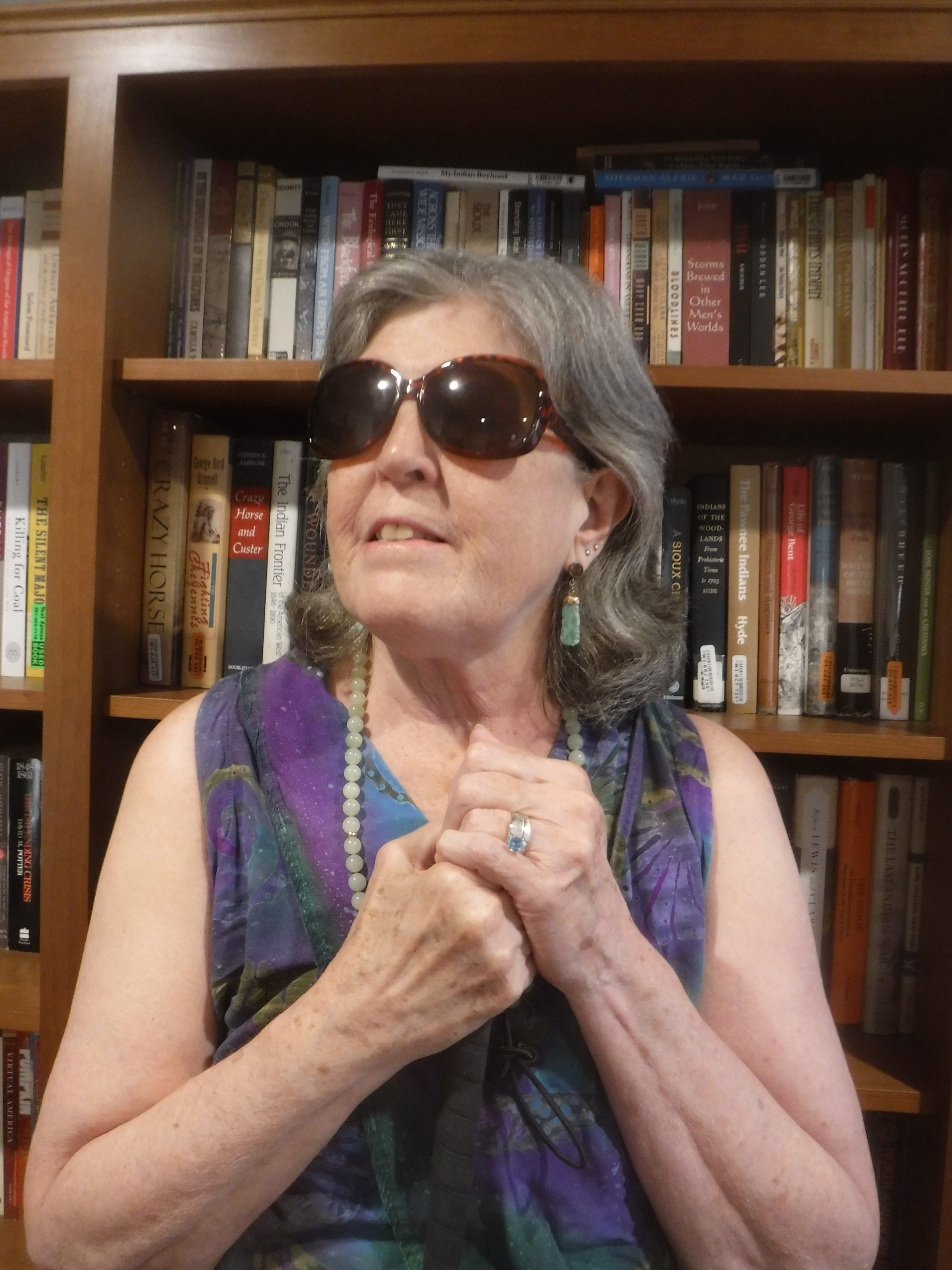

-Alida Boorn is an Independent Historian who is currently working on advocacy in Disability History scholarship in academia, museums, and archives. Additionally, she is doing research for a biography of deafblind Plains Indian historian George E. Hyde. Her dissertation is titled “Interpreting the Transnational Material Culture of the 19th – Century North American Plains Indians: Creators, Collectors, and Collections” (Kansas State University, 2016). She can be reached at alidaboorn@gmail.com.

Header: Author portrait taken by James Boorn 7/12/2020.

Notes

- William J. Eaton, “Disabled Persons Rally, Crawl Up Capitol Steps : Congress: Scores protest delays in passage of rights legislation. The logjam in the House is expected to break soon.,” Los Angles Times, March 13, 1990, HTTPS://WWW.LATIMES.COM/ARCHIVES/LA-XPM-1990-03-13-MN-211-STORY.HTML accessed 8 July 2020, Stephen Kaufman, “They abandoned their wheelchairs and crawled up the Capitol steps,” ShareAmerica U.S. Department of State, March 12, 2015, https://share.america.gov/crawling-up-steps-demand-their-rights/ accessed 8 July 2020.

- For more information on the Disability Movement recommend “Colorado Experience: The Gang of 19 ADA Movement,” produced by Rocky Mountain PBS, 2018, and “Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution,” distributed by Netflix, 2020.

The WHA Round Table session for 2020 did take place in Oct. WHA members can view the session at the WHA website.