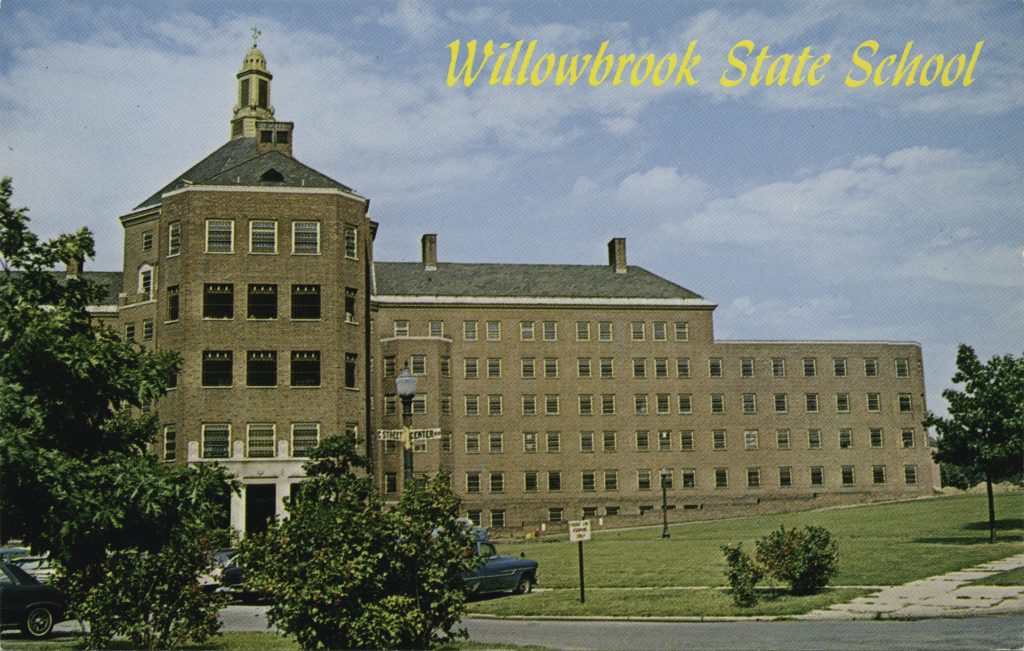

In 1992, the College of Staten Island (CSI) was preparing for a big move. Edmond L. Volpe, the first president of CSI, was excited about the relocation from the neighborhood of Sunnyside to Willowbrook, expressing that the new 204-acre campus was “going to be beautiful.” With this move, the hope was that the “abandoned grounds of the old Willowbrook State School would no longer be permeated with sadness.”

Six years prior, Willowbrook was anything but beautiful. Misery, mistreatment, disease, and trauma run deep in the bowels of its past.

Founded in 1942 as a facility for children with intellectual and developmental disabilities, the Willowbrook State School became well-known for neglecting and abusing students through childhood and adulthood. The students were residents that lived on-site, which made it possible for the institution to isolate itself and escape criticism until three residents died in 1965. After countless scandals, court cases, and years of public discourse, Willowbrook closed its doors in 1987—three years before the American with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 was passed.

Since the enactment of the ADA, New York has done better in addressing institutional neglect and abuse. Despite improving, New York still struggles to provide all disabled people with the accommodations and services that they deserve. Moreover, the legacy of Willowbrook’s abuse still continues to harm people today.

Earlier this year, the New York Times’ Benjamin Weiser reported that a 57-year old woman named Migdalia was abused at one of the small group homes where Willowbrook’s residents moved to after a 1975 federal court ruling. Migdalia could not call for help because she is nonverbal. She was in need of someone to speak up for her when she suffered bruises on her limbs and a “shoe print on her belly.” Migdalia was not the only victim.

According to Weiser, 2,300 of Willowbrook’s alumni are alive today and many continue to experience mistreatment. The ADA applies to people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, but New York does not treat those people with a sense of urgency. People with those disabilities oftentimes cannot defend and speak for themselves, which makes it easier for the state to ignore them.

Recent events put the efforts of improving services for the disabled in jeopardy. Like many states, the COVID-19 pandemic has been a financial strain on New York. Governor Andrew Cuomo’s proposed budget will significantly cut Medicaid. This is alarming, for it is reminiscent of the New York City financial crisis of the 1960s and 1970s that significantly affected the residents of Willowbrook and put the national spotlight on the facility’s abusive practices. Despite increased occupancy, budget cuts led to staff reduction; in 1965, three residents at Willowbrook died because of inadequate supervision.

These tragedies caught the attention of Senator Robert Kennedy and prompted him to visit the facility unannounced. Senator Kennedy was appalled by the conditions that the children and adult residents of Willowbrook lived in, observing that they “lived in filth.”1 Since the injustices at Willowbrook were happening in the middle of the Civil Rights Movement, the conditions at Willlbrook convinced Senator Kennedy that “there [were] no civil rights for young retarded adults” who were neglected by state facilities that did not serve them and give them an education.2

Abuse continued at Willowbrook despite Senator Kennedy’s visit and it was clear that the problem stemmed from New York itself. The post-World War II economy and white flight contributed to the issues of racism and ableism. Upper and middle-class whites moved to nearby suburbs upstate or in New Jersey, which led to a decreased tax base. This allowed suburbanites and others in New York State to develop a cultural disdain towards New York City and the many people of color that were left behind there. By 1975, New York City did have enough funds to pay for city operating expenses. In the summer of 1977, a blackout affected the city for over twenty-four hours. Black and Latinx communities were hurt significantly more than their white counterparts because their neighborhoods were more susceptible to damages. These are the communities that suffered the most during this era. The same applies to disabled people who were seen as fiscal burdens during a time of great distress.3

In 1972, WABC aired a Geraldo Rivera exposé titled “Willowbrook: The Last Great Disgrace.” It showed America what the residents of Willowbrook experienced. The conditions the children and adults lived in appalled the nation. In the exposé, Rivera argued that simply throwing money at the problem would not be enough in ameliorating conditions at Willowbrook. He believed that the state should have the goal of allocating funds towards improving the facility and creating educational programs that would give residents the means to improve their quality of life.

New York fell short of that goal.

The 1975 federal court ruling that placed thousands of Willowbrook residents in small group homes was made possible by the exposé. The small group homes were supposed to provide good conditions and educational programming for their residents. Instead, problems persisted because the state did not adequately supervise the small group homes. This allowed residents like Migdalia to suffer in silence. It is cases like Migdalia’s that show that New York continues to battle the shadow that Willowbrook cast on the care for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Thankfully, state institutions such as CSI are confronting that large shadow with the tools the ADA has provided institutions.

The American with Disabilities Act allows CSI to succeed in confronting the legacy of the Willowbrook State School. CSI’s main campus at Willowbrook and its two other locations in Staten Island serve all kinds of students. This college is not antithetical to the Willowbrook State School because it serves able-bodied and neurotypical students. This college is antithetical to the Willowbrook State School in that it wants its students with disabilities to be as successful as their able-bodied and neurotypical counterparts. In tearing down the Willowbrook State School’s building and making it a grassy space called the Great Lawn, CSI has created its own legacy by making the Great Lawn the place where its commencement ceremonies are held. When students’ name are said during commencement, the legacy of Willowbrook is dismantled piece by piece because every CSI graduate represents hope for a better future.

As a student who graduated from CSI with a Public History Advanced Certificate, I am appreciative that the hope bestowed onto me does not mean that CSI is trying to erase its past. CSI’s Archives and Special Collection is documenting the “unofficial” history of the Willowbrook State School by collecting archival materials and stories from residents, parents, and staff members with memories to share. CSI does not own official Willowbrook records, which prompted the CSI Archives to compile a list of official materials on Willowbrook that are held at archives around the country for researchers. These efforts show that CSI believes that “the history of the Willowbrook State School is crucial to understanding the history of the treatment of people with developmental disabilities.”

It is apt that CSI is fighting this fight because it literally hits home. The ADA of 1990 has given states the tools to do better despite the challenges that lay ahead. Now it is up to us to urge our legislators to use those tools. CSI turned the former grounds of the Willowbrook State School into a place that develops professionals regardless of race, religion, gender identity, sexual orientation or disability. If CSI could do that, New York could give all people, especially those with disabilities, the attention and resources they have always deserved.

Carlos A. Santiago is a public historian based in New York City. Carlos currently works at the The New York Genealogical and Biographical Society where he preserves genealogical records and makes them available online. He is a student of the history of tourism and the New Deal in Puerto Rico.

Header Image: College of Staten Island in Spring 2018. Photo taken by Carlos A. Santiago, May 7, 2018.

Notes

- “Excerpts From Statement by Kennedy,” New York Times (New York, NY), September 10, 1965.

- Ibid.

- Brian Tochterman, The Dying City: Postwar New York and the Ideology of Fear, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017), 1-3.