The fight of disability rights in the United States has included several Japanese-American citizens who served as local, state, and national officials. Many became involved because of personal experiences, including the mass incarceration and combat during World War II. Yet, their significant contributions to the development of the Americans with Disabilities Act has mostly been overlooked.

On February 19, 1942, six weeks after the Japanese military bombed Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066. The exclusion order forced 120,000 Japanese-Americans and their families into incarceration camps in Arizona (Poston and Gila), Arkansas (Jerome and Rohwer), California (Manzanar and Tule Lake), Wyoming (Heart Mountain), Utah (Topaz), Colorado (Amache), and Idaho (Minidoka).

Disabled people were initially exempt from the exclusion order. However, in the end, except in cases of severe disability, such as Ron Hirano, Taeko Hoshida and Toyoki Kurima, everyone else, including children, accompanied their families to camp. Taeko Hoshida and Toyoki Kurima were placed in institutions when their families were sent to camp and died there before their families returned. Ron Hirano was another exception. He was the only one of eleven Deaf students at the California School for the Deaf and Blind to be exempt, because his parents were afraid that his education would suffer in camp.

Although conditions were bleak, parents and authorities attempted to create a normal an environment as possible. Graduation ceremonies were held and schooling resumed at the assembly centers within weeks. And, after everyone was moved to permanent facilities that summer, school resumed in September. But it was almost a year before the first school for children with disabilities opened at Manzanar incarceration camp. More opened in other camps, including Tule Lake.

Hannah Takagi, a former student at the California School for the Deaf moved to Tule Lake with her family, hoping to get a better education than she had at Manzanar. Unfortunately, it did not work out. She recalled:

“Children suffering from deafness, blindness, mental [disability], and physical paralysis were lumped into one class under the supervision of a teacher…who understood the needs of none of us. She did not even allow me to use sign language.”

Takagi did have “one truly rewarding experience” at the school. After students decided to rename it the Helen Keller School, Takagi wrote to Keller whose reply was published in the camp newspaper:

“I am glad of the chance that the children there have to learn to read books, speak more clearly and find sunshine among shadows. Let them only remember this-their courage in conquering obstacles will be a lamp throwing its bright rays far into other lives beside their own.”

In addition, disabled people entering the camps, the poor living conditions often led to babies being born with disabilities. The Matsui family was sent to Tule Lake. There, their son Robert got an ear infection and a high fever. Years later, he learned that, because of the infection, he lost 20% of his hearing in both ears. But that was not all. Alice Matsui contracted German measles (rubella) while pregnant. The family moved to the Minidoka incarceration camp in Idaho where Barbara was born blind. However, Matsui does not believe that his conditions in the camp caused his hearing loss or his sister’s blindness. “I wouldn’t want to even speculate,” he said, explaining that those illnesses could have happened at any time in those days.

Tama Tokuda became pregnant with her eldest child Floyd in Minidoka. Unfortunately, “the camp doctor, this Caucasian guy, gave her a very powerful antibiotic for a kidney infection” resulting in Floyd being born mentally disabled.

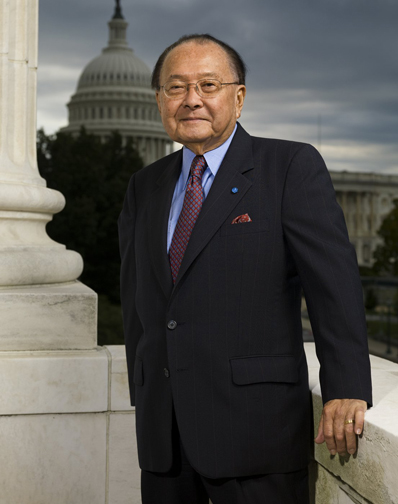

Additionally, among the over 33,000 Japanese-Americans who served in the American military, many became disabled during combat, including Daniel Inouye and Masayuki “Spark” Matsunaga, from Hawaii. Both became disabled while fighting in Italy. Inouye lost his right arm and Masanaga’s right leg was severely damaged.

The ADA

Decades later, Inouye and Matsunaga became Senators.

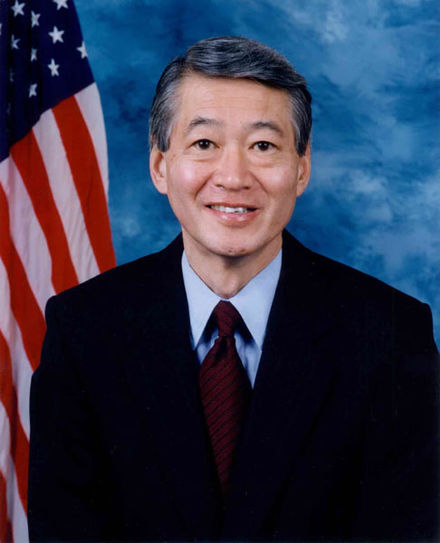

They joined Congressman Matsui, and Congressman Norman Mineta — whose family had been incarcerated at Heart Mountain — in supporting the ADA. Additionally, many civilians were also involved in the movement, including Justin and Yoshiko Dart, and Michael Winter and Atsuko Kuwana. Yoshiko and Atsuko are first generation Japanese-Americans. Both Kuwana and Winter use wheelchairs. Kuwana used a wheelchair due to a spinal cord injury at birth, and Winter used a wheelchair due to osteogenesis imperfecta (or brittle bone disease).

The Darts would help start the movement and Winter and Kuwana would help finish it.

Justin, who contracted polio as a teen, became the “father of the Americans with Disabilities Act“. In 1981, President Ronald Reagan appointed Justin as the vice-chair of the National Council on Disability. The Council would create a policy proposal to end disability discrimination, that would become the ADA framework.

In 1988, he was appointed chair of the Congressional Task Force on the Rights and Empowerment of Americans with Disabilities. He and Yoshiko toured the country advocating for the ADA. They met citizens in every state, Puerto Rico, Guam, and D.C. and held public forums 8th drew more than 33,000 people. They met congress members their staff, President Bush, Vice President Quayle, and Cabinet members to gather support.

Yoshiko later called the disability rights movement as “Magnificent” and noted that “It might be one of the last frontier movements in human development.”

Unlike the others, Mineta did not have any personal connection to disability. Instead, he became involved with disability rights through a friend while running for San Jose mayor:

“I had a friend working on my campaign named Bill Poole, who’d been in a wheelchair all his life. One day he asked me whether I would consider spending my first week as mayor in a wheelchair….I put a wheelchair in my trunk each morning, and quickly realized how difficult things were for Bill and people with disabilities. I couldn’t get up the stairs to City Hall. I couldn’t go to the bathroom. I couldn’t get a drink from the public fountain.”

This experience led Mineta to work on the transportation portion of the ADA. At the subcommittee hearing in 1989, Mineta explained that, “Many disabled individuals have cited a lack of transportation as the chief barrier to full participation in their communities.”

But their support and campaigning were not enough. When the bill failed, Kuwana was one of the “more than 8,500 citizens with disabilities, their advocates and organizations from every state who signed and paid their scarce dollars to sponsor this petition for justice,” who urged the House to pass the bill in February 1990.

A month later, Winter participated in the Capitol Crawl. On March 12, he and other activists including 8-year-old Jennifer Keelan, got out of their wheelchairs and crawled up the front steps of the Capitol building.

Their efforts paid off and the bill move to the Senate. At the hearing, Daniel Inouye said that July 13, 1990, “will mark one of the greatest accomplishments of the 101st Congress” and in signing the ADA, “Washington signals a new beginning for 43 million Americans with physical and mental disabilities…” Quoting Senator Tom Harkin who introduced the bill, Inouye called it,

“nothing less than an ‘emancipation proclamation’ for people with disabilities who will finally benefit from civil rights protections in the areas of private sector employment, State and local public services, public and private transportation services, privately owned public accommodations, and telecommunications relay systems.”

The Darts and Atsuko Kuwana were at the White House when President Bush signed the ADA into law on July 26, 1990. Justin sat beside President Bush and is captured in the famous photograph. Bush later sent a signed copy to the Darts with a note.

Yoshiko took many pictures, including one of Kuwana with Senator Ted Kennedy and other activists after the signing. Michael Winter would serve as “a key adviser” to Transportation Secretary Mineta from 2001 to 2006.

The Aftermath

At the state level, Washington legislator Kip Tokuda, Floyd’s brother, advocated for many disabled people including those with developmental disabilities. After the ADA passed, he sponsored the “an act relating to supported employment for persons with development disabilities” and “Act Relating to dog guides and service animals” to amend Washington laws “related to guide and service dogs [which] is inconsistent with the Americans with Disabilities Act.” He was also instrumental in passing the “Special Needs Adoption” bill.

Others enforced the ADA as private citizens. In Oregon, architect Kenneth Takao Nagao “worked for the city of Eugene and other nearby cities, inspecting schools and municipal buildings for handicap accessibility and compliance.”

Thirty years later, there is still much to be done, and the next generation continues to fight. Rosemary McDonnell-Horita, who has brittle bone disease, still struggles to get around. While helping organizations increase accessibility for their space and programs, she still has to make sure that businesses can accommodate her wheelchair. Even now, she says, “There’s still a lot of stigma, there are still a lot of people who think people with disabilities are helpless. A lot of people remain unaware.”

But there is some progress during the current health crisis. McDonnell-Horita notes that the transition online has made it easier for some people with autism to participate. And, as part of its outreach, the Clyfford Still Museum began weekly webinars and classes, and “without being asked they made sure the webinars were closed captioned…[which] allows people to join in without having to plan, without having to ask for it in the first place.”

Atsuko Kuwana and her son returned to her hometown in Japan annually to visit her family. In 2003, she spoke at an elementary school and shared her experiences. One of the questions students asked was “What is the difference between Japan and America [with regard to disability access]?” Kuwana replied,

“In America there are laws that protect people with disabilities so they can live and work together with people who don’t have disabilities. Buildings must have ramps and elevators and accessible toilets. It’s against the law to discriminate against people with disabilities. If some place isn’t accessible, we can use those laws to ask for changes. That’s a big difference.”

-Selena Moon received her BA in history from Smith College and MA in history and public history certificate from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. She studies Japanese American mixed race and disability history. She can be reached at selena.m.moon@gmail.com, on Twitter at @SelenaMMoon or her website selenammoon.com.

Header: Photograph of Tei Kaneko and her son Wayne (right) and nephew Robin Isoda (left) in a resettlement home in Milwaukee, Wisconsin (1944). Photo by the War Relocation Authority, Densho Digital Repository.