“One by one, people dragged themselves up to the second, the third, the fourth step. Some inching forward on their backs, others lying on their bellies, their bodies and legs trailing behind. Using an elbow, a knee, a shoulder, they pulled themselves up…Over sixty people climbed the steps.”

–Judith Heumann1

The first version of the American with Disabilities Act failed.

Introduced to Congress by Republican Senator Lowell Wicker and Democratic Congressman Tony Coelho in April 1988, the draft legislation was only the beginning. Its provisions were meant to address an “appalling problem: widespread, systemic, inhumane discrimination against people with disabilities.” Disabled children were excluded from public schools. State residential treatment institutions were abysmal, overcrowded, and inhumane. Disabled people were barred from employment, public transportation, or even shopping. They were routinely denied full civil rights: to drive, to hold public office, to marry, to bear children.

When Congressman Major Owens of New York organized the Congressional Task Force on the Rights and Empowerment of People with Disabilities, the goal was to increase awareness of disability and gather evidence to support anti-discrimination protections to be included in the revised version of the ADA. The Task Force Chair, Justin Dart, decided to unify the movement by including HIV-positive people, and holding public hearings across the country to document the injustice and discrimination faced by disabled people. A national campaign was also initiated for people to send in their “discrimination diaries,” which chronicled their lived experiences of disability, in an effort to raise awareness about barriers to their daily living.

Seven hundred people attended the September 1988 joint hearing held before the Senate Subcommittee on Disability Policy and the House Subcommittee on Select Education. These included blind people, physically disabled people, deaf people, people with Down Syndrome, HIV-positive people, as well as a parents of disabled children. They demanded more than “separate-but-equal” policies.

A year later, the ADA passed.

Politics and government delayed its enactment. Frustrated, disability activists and advocates took to lobbying and protests, demanding the House committees prioritize the legislation. Months passed with more delaying tactics, until on March 12, 1990, thousands of activists from thirty states marched to Capitol Hill in Washington D.C. to demand the passage of the ADA. They called for immediate action. After a series of rallies and speeches, sixty activists abandoned their crutches, wheelchairs, walkers, and climbed the 83 stone steps that led up to the Capitol to symbolize the barriers disabled people experience daily.

Disabled activists climbing the steps of the Capitol in Washington, D.C., on March 12, 1990, to push for the passage of the American With Disabilities Act. Photo by Tom Olin via Disability History Museum

The Capitol Crawl became a catalyst: four months later, Congress passed the legislation. On July 26, 1990, President George H.W. Bush signed the ADA into law. “Let the shameful wall of exclusion finally come tumbling down,” he said upon signing.

The activism by disabled people and the signing of the ADA were historic. It began with disabled people, but more importantly, it succeeded by the result of a coalition. As Fred Pelka expressed:

“Never before, and not since, has such a broad coalition of disability groups and activists united around a single issue. The goal was to pass a federal civil rights act to extend basic protections against discrimination, and thus ensure equality of access to employment and the public arena, to all Americans with disabilities.”2

Decades of Battles

While the transition from “pity to fear” to “equal citizenship” has been revolutionary, the work for disability rights began long before the drafting of the ADA.3 Since the start of the twentieth century, disabled people have organized for their rights in various ways: clubs and organizations, labor and union movements, postwar “Hire the Handicapped” veteran campaigns, rehabilitation and medical access, and access to equal education.

These organizations served to address stereotypes and pejorative attitudes that were used to justify racial, gender, and class oppression, particularly since disabled people were the “most explicit targets of eugenics movement.”4 Paternalistic legislation, forced sterilization, and institutionalization or incarceration further victimized disabled people.

The success of the Civil Rights movement sparked the resurgence of disability rights. It showed many disabled organizations how “litigation and legislation are useful tools for advancing a disability rights agenda.”5 At the University of California, Berkeley for instance, disabled people were ignited by the campus’ political spirit. Anti-war protesters, feminist rallies, and the People’s Park Protest—all the “Free Speech Movements” more generally—inspired disabled students to seek out a space for themselves.

Ed Roberts (1939-1995), the first quadriplegic student admitted to university in the United States, for example, used his success with obtaining student accessibility to convince Berkeley to accept more quadriplegic students into degree programs. These students, who devoted themselves to campus activism, community building, and self-advocacy, often referred to themselves as the Rolling Quads. By 1972, the group renamed themselves as the Physically Disabled Students Program and expanded to the broader cityscape and established the Center for Independent Living (CIL).

The CIL served as a community hub for disabled people. They published a magazine, The Independent, which featured articles offering advice for employment, access, and independent living. They also collaborated with the city to build the first planned, wheelchair-accessible route in the United States, leading to the creation of flourishing and vibrant communities of disabled people.

Direct-action disability rights group also emerged in other parts of the county. Disabled in Action founded by Judith Heumann played a leading role in the campaigns to pass Section 504 of the 1973 Rehabilitation Act, which prohibited discrimination on the basis of disability by any public or private entity receiving federal funds. The American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit (ADAPT; renamed Americans Disabled Attendant Programs Today in 1990) which started in Denver in 1974, organized demonstrations against wheelchair inaccessibility of public buses. Even the Deaf President Now! campaign of 1988 served to achieve self-determination and empowerment for deaf people.

These activists’ efforts eventually culminated into what lobbyist Patrisha Wright dubbed as “the golden age of disability rights legislation.”6 Multiple laws were passed, including: the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (1975), now Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA); the Civil Rights of Institutionalized Persons Act of 1980; Voting Accessibility for the Elderly and Handicapped Act of 1984; Air Carrier Access Act of 1986; Fair Housing Amendments Act of 1988; Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1988; and then, the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990.

Decades of work, it seems, finally allowed disabled people to achieve their civil rights. If you’ve watched the Netflix documentary Crip Camp (and if you haven’t, do so!), you’ve learned that much of the activists’ fight was for dignity: for the freedom to make their own decisions, to move and live independently, and for access to the adaptive and assistive things that they need to be self-sufficient.

Their stories are about dismantling barriers. They fought not just for themselves, but for future generations. “You drop a petal in the water,” Judith Heumann writes, “and it has a ripple effect.”7

The ADA Generation

“This may feel true for every era, but I believe I am living in a time where disabled people are more visible than ever before. And while representation is exciting and important, it is not enough. I want and expect more. We should all expect more. We deserve more.”

-Alice Wong8

It took me a long time to come to terms with my deafness. I spent years attempting to pass as hearing, pretending I heard more than I did, forcing myself to practice speech therapy, and denying myself sign language. The struggle was part of the success, I convinced myself – if I could manage to achieve my goals despite of my deafness, then it just proved it didn’t matter.

I wish I could speak to my younger self and tell her that her deafness was nothing to be ashamed of, and that she doesn’t need to carry the weight of her internalized ableism. I wish I could tell her that she should be proud and that there are resources in place for her to find a community and a sense of belonging – and that she should of course, fight to make the same access available to others who need it. I wish she learned that joy could come from self-affirmation.

I’m not American, so I didn’t grow up in the light of the ADA. But having lived and worked in the United States for the past few years, I have benefited from its provisions. I have also seen the many ways that that the ADA is ignored by companies that have failed to comply with accessibility requirements. I have learned—and witnessed—how stigma and discrimination against disabled people are still deeply entrenched in the fabric of American society.

Disability activist Rebecca Cokley coined the term “ADA Generation” to define “the first generation of disabled advocates who grew up at the intersection of IDEA and ADA.” This group encompasses the 20 million people who “grew up knowing the transformative civil rights law as a birthright. They expect the law to guarantee, not just promise, that they will get access to transportation, jobs, schools and other public places and to the same opportunities as anyone else.” For many of them, disability is identity and pride. As Joseph Shaprio elaborates, this generation also “grew up expecting its rights but also found resentment instead—propelling a need to keep pushing back.”

Disabled people can have a culturally rich life but still feel discriminated against on the basis of their disabilities. They can’t marry without sacrificing their benefits eligibility, so they fight for marriage equality. They are the first targets of healthcare rationing debates, disproportionately impacted by systemic medical biases, including ableism and racism. They are the first to place their bodies on the line in the fight for healthcare equality. Their requests for reasonable accommodation are frequently scoffed at and denied, while at the same time, their need for exceptions are made into mockery. They pay Crip Tax to access goods and services. Black disabled people face the added prejudice of racism as they reclaim their place in the disability movement. And even as disabled people share their experiences of living with invisible and visible disabilities, the performance of emotional labor, their own internalized ableism, or their frustrations with accessibility as an afterthought, many still report a high level of happiness and a good quality of life. This is the disability paradox: disabled people’s experiences contradict the commonplace view of disability as an instance of harm, or as a life not worth living.

The stories of disabled people add to the richness of our cultural heritage, but it is important to acknowledge that their struggles were not erased the moment the ADA was signed into law. Thirty years later, disabled people still face significant challenges and discrimination. Activists and advocates continue the fight. The coronavirus pandemic, for instance, nearly immediately made remote work and learning accessible, features that disabled people have been demanding for decades but been denied. As Imani Barbarin notes, this is a strange paradox, but another reminder that

“While life has become more inclusive for everyone else, life itself for disabled people hangs in the balance.”

It seems perfectly fitting then, that ADA TURNS 30 serves as the first special series for All of Us. We sought out a wide variety of submissions—historical research, personal narratives, commentary on current events, educational initiatives—and we are pleased by the breath and scope of the essays. Most of the submissions came from disabled academics, activists, and community members. As Series Editor, it has been an absolute delight reading through all the submissions and I want to thank all the authors for considering All of Us as a platform for their writing.

Over the next few weeks, we’ll be featuring essays in the ADA TURNS 30 series. These essays center disabled stories and chronicle the multitude of disability experience both before and after the ADA. We hope you enjoy ADA TURNS 30 and are encouraged to send in your own submissions to be published on All of Us.

–Jaipreet Virdi is an Assistant Professor in the Department of History at the University of Delaware whose research specializes on the ways medicine and technology impact the lived experiences of disabled people. She is author of Hearing Happiness: Deafness Cures in History, co-editor of Disability and the Victorians: Attitudes, Interventions, Legacies, and creator of Deaf History Series. You can find her on Twitter as @jaivirdi.

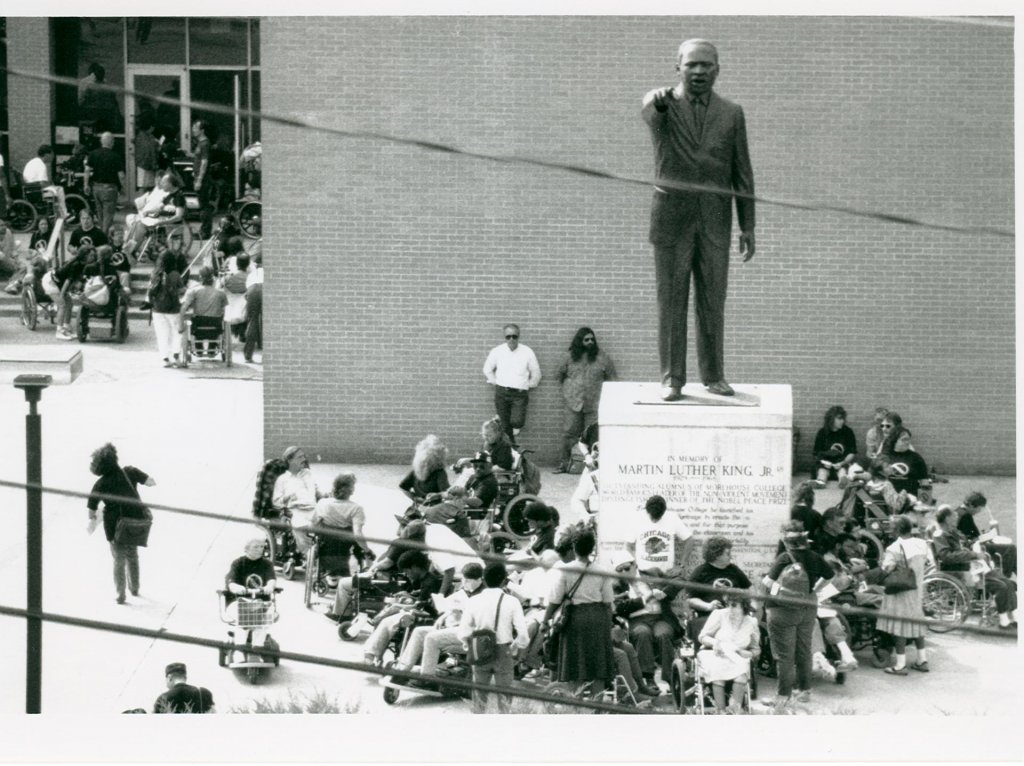

Header: ADAPT activists surround a statute of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Photograph by Tom Olin, via Smithsonian National Museum of American History.

Notes

- Judith Heumann, Being Heumann: An Unrepentant Memoir of a Disability Rights Activist (Boston: Beacon Press, 2020), 170.

- Fred Pelka, What We Have Done: An Oral History of the Disability Rights Movement (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012), 413

- Pelka, What We Have Done, 4

- Pelka, What We Have Done, 10

- Pelka, What We Have Done, 24

- Quoted in Pelka, What We Have Done, 28

- Heumann, Being Heumann, 197.

- Alice Wong, “Introduction,” in Alice Wong (ed.), Disability Visibility: First-Person Stories from the Twenty-First Century (New York: Vintage Books, 2020), xvi.