Home to geothermal springs that were long believed to have curative properties, the city of Bath in southwest England has drawn people from Great Britain and Europe seeking cures for their sicknesses for centuries. The Romans built a bath complex in the city and named it Aquae Sulis. Bath’s popularity as a town of curative properties increased in the seventeenth century after several royal visits drew attention to the area and resulted in an influx of poor, sick, and disabled people hoping their illness would invite generosity.

“Such multitudes of Beggars come hither, partly for cure, and partly for relief, that the ‘Sturdy Beggars of Bath’ are become a proverb.”1

The growing influx of the sick and poor into the city elicited concern and suspicion that some of the “Beggars of Bath” were actually taking advantage of the opportunities to beg for alms. Indeed, the “Beggars of Bath” were described as being “insolent, vociferous and sturdy.” In response, Bath philanthropists proposed plans for an entirely self-funded hospital to provide the poor and sick with treatments using the famed healing waters of the city and to regulate the flood of beggars into the city.

A New Institution

Between 1716 and 1723, a Committee of Friends started fundraising for a hospital. Nearly a fifth of the total funds to set up and open the hospital were raised by Beau Nash, who made his fortune gambling and who served as Master of Ceremonies in Bath. Fundraising also ensured that some costs for patients were covered by “caution money”: this was derived from the parish where the patient lived and was used to pay for the cost of clothes, their passage home and if necessary, and their burial costs.

Source: Healing Waters of Bath, Virtual Exhibit, Michigan State University.

After years of wrangling over the location of the hospital, the trustees settled on the site that was the old Playhouse. The finished building was built with traditional Bath stone donated for free and described as “a magnificent pile of building.” The site additionally contained a bakehouse, brewery and laboratory. The “houses of offices” (toilets) weren’t connected to the city’s sewers until 1764, as it hadn’t occurred to anyone that simply draining the waste into a ditch wasn’t ideal for the health of the patients.

The hospital opened in May 1742 as the Bath General Hospital and soon became a lifeline for chronically ill and disabled patients who had been left to fall into poverty due to their impairments. But the Hospital itself was also intended to control the flow of disabled poor to the city. This is clear when we consider the criteria for admissions to the hospital: “The case of the patient must be described by some physician or person of skill, in the neighbourhood of the place where the patient has resided for some time; and this description must be sent, franked or post paid, directed to the Register of the General Hospital at Bath.” Soldiers were also permitted into the hospital, with a certificate from their commanding officers, signifying their corps, as were pensioners from the Chelsea and Greenwich hospitals. Poor people coming to Bath “under pretence of getting into the Hospital” who did not have the accompanying documentation were treated as vagrants.

The Patient Experience

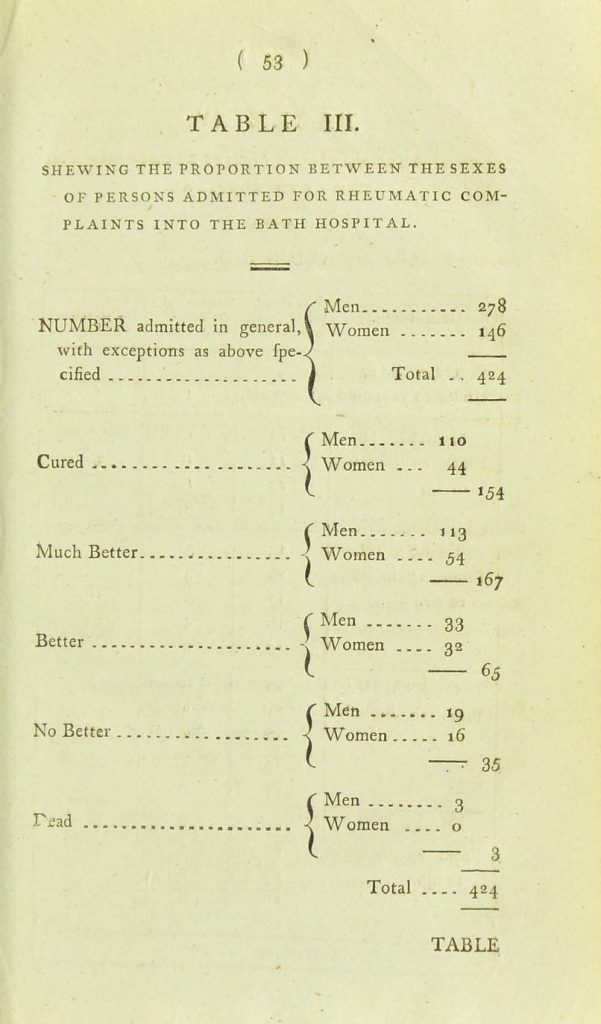

Patients would regularly stay for a year or more. Unusually, the hospital functioned predominately as a rehabilitation facility rather than an acute medical center. Given the chronic and disabling nature of the patients’ conditions, many were admitted for a long duration; they would often stay in-patient until the hospital could publicly report in newspapers a prognosis: cured, much better, better, no better, and dead. The need to confirm patient outcome meant the hospital became forward-thinking in terms of symptom management for patients, including with hydrotherapy, waterbeds to prevent bedsores, and employing strict diet and exercise to manage chronic symptoms.

Due to the sheer length of the average stay for patients, they were regularly allowed out to enjoy the city. When outside the hospital they were required to wear a brass badge to identify them as patients to the public, the police, and pub owners. Unruly behaviour by patients and staff was common: on at least one occasion the hospital staff were caught getting drunk with the patients in the baths. Graffiti was a common occurrence as were fistfights. One patient was even heavily fined for damage carried out while racing his wheelchair around the hospital.

William Falconer, An Account of the Use, Application and Success of the Bath Waters in Rheumatic Cases, (Bath: W. Meyler, 1795), 53.

For the first few years, the majority of patients in the hospital were injured soldiers. By mid-century, the hospital shifted towards specialist treatment in paralysis (e.g. “palsy”). Another frequent condition treated was “colic” (sudden severe abdominal pain) which regularly transformed into palsy (paralysis often with muscle contractions). For instance, William Bishop, a farm labourer from Somerset, developed paralysis after he, and his fellow workers, received payment in vast quantities of traditional cider in lieu of money. Local physicians were stumped and unable to diagnose or treat the men; but within a few weeks of treatment at the hospital, Bishop and his men recovered use of all their limbs.

The lengths that many desperate people had to go to before receiving treatment at the hospital could be shocking. A Welsh sailor’s apprentice on a trading voyage to Gibraltar and Russia was struck by lightning, and after keeping him on the boat for four months didn’t cure him, he was sent to the Bath for the treatment of his paralysis. Allen Lane was another young sailor who required treatment. After landing in the West Indies, he had become acutely ill, and by the time he was able to return to England and seek treatment he was covered in hard swellings and all of his limbs had contracted so severely they couldn’t be moved. After twenty months in the hospital with no treatment other than mild laxatives, a good diet and regular baths in the hot waters, he could walk unaided.

Credit: College of Arms.

Constant Issues

From the start, however, the hospital has had three constant issues: lack of money, lack of space, and unruly patients. Inevitably, for a self-funded hospital providing treatment to the poor from all over the country, money had always been difficult. Many parishes didn’t keep up with their payments to the hospital and had to be chased down until they paid up. Within three years of the hospital opening, there had to be major spending cuts. By 1746 the hospital’s Governors decided that “in future, chairmen shall have a greatcoat provided every other year instead of annually and that lace trimmings shall be omitted from their hats.”2

One solution was to charge patients who had some financial means, but this went completely against the rules of the hospital and would have required an Act of Parliament. Nevertheless, any surplus funds were earmarked towards expanding as overcrowding of sick people wanting to “take the air” was a constant problem. Patient activities were also restricted. They were not allowed to partake in any of the activities that would make a long stay in hospital bearable. The only books available were the bible and a prayer book, there were no pictures on the walls, and male and female patients weren’t allowed to talk to each other.

The Bath General Hospital had a remarkable success rate for patients recovering and being entirely relieved of their symptoms. It had also been at the forefront of rheumatological research since its opening. The name was changed in 1837 to the Royal Mineral Water Hospital, and thus the nickname of “The Min” was born. It was renamed again in 1936 to the Royal National Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases. and continues to be used by locals today.

The original building with its alterations is still a central focal point of the city of Bath, but for many years now, plans have been in motion again to re-site the hospital. Despite an attempt by the local community to dedicate the building as an Asset of Community Value, it was sold to a private developer in 2017. The final services moved to the new site in October 2019, with the closing of the original grade II listed building soon after and the loss of the oldest national hospital in Britain.

–Daisy Holder is a Disability Activist, Captioner, and Open Source Researcher. She is 27, has been disabled for 13 years and lives in Bristol, U.K. She blogs about disability history at www.daisythechronicinvalid.com Get in touch on twitter @daisyholder or email daisythechronicinvalid@gmail.com.

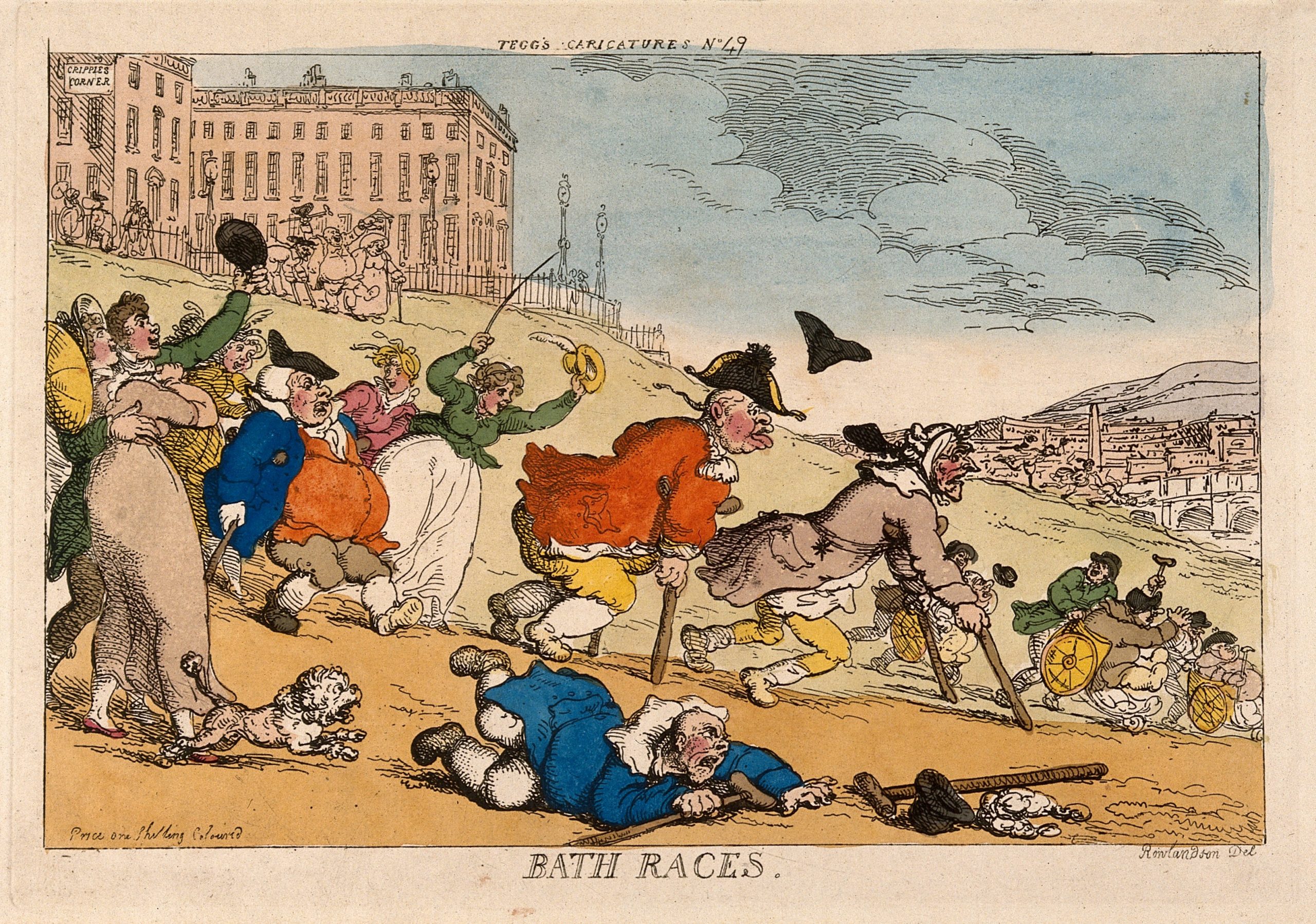

Header Image: “Bath Races” (1810) Colored etching by Thomas Rowlandson. Wellcome Collection.

Sources Consulted

Your Min: RNHRD, rnhrd.nhs.uk

Randle Wilbraham Falconer and Anthony Beaufort, History of the Royal Mineral Water Hospital (Brabazon, 1888 edition).

Pierce Egan, Walks Through Bath, Describing every thing Worthy of Interest, Including Walcot and Widcombe, and the surrounding vicinity, also an excursion to Clifton and Bristol hot-Wells, Bath: Meyler and Son, 1819, 18.

Catherine Pitt, “Finding the Cure,” The Bath Magazine (2012).

Clive Quinnell, The History of the Mineral Water Hospital In Bath (BRLSI Bath Institutinos Millenium Series, 2000).

Robert Rolls, The Hospital of the Nation: The Story of Spa Medicine and the Mineral Water Hospital at Bath (Bird Publications, 1988).

Notes

- Mackay’s Journey through England, p.413 cited in Falconer and Beaufort, History of the Royal Mineral Water Hospital, 10.

- Minute book 20.284, held by the archives of the Royal National Hospital of Rheumatic Diseases. Quoted in Robert Rolls, The Hospital of the Nation: The Story of Spa Medicine and the Mineral Water Hospital at Bath (Bird Publications, 1988).