On January 7, 2022, Dr. Rochelle Walensky, the Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, gave an interview to ABC News about the current state of the Covid 19 pandemic. When asked about a study showing how effective vaccines are at protecting against severe illness and death from Covid 19, she said:

If I may just summarize it. A study of 1.2 million people who were vaccinated between December [2020] and October [2021] and demonstrated that severe disease occurred in about 0.015 percent of the people who received their primary series and death in .003 percent of those people. The overwhelming number of deaths, over 75 percent, occurred in people who had at least four comorbidities. So, really these are people who were unwell to begin with, and yes, really encouraging news in the context of Omicron.

Her language, specifically that those who died from the virus “were unwell to begin with” and that this was, therefore, “really encouraging” news, sparked outrage and a hashtag: #MyDisabledLifeIsWorthy.

Many disabled Americans have felt left behind by the government’s response to the pandemic. The removal of mask mandates has only worsened that feeling. The CDC stated that those at risk, or who are immunocompromised, can continue to wear them. The problem, however, is that mask wearing is much more effective when all in a group wear masks. Therefore, the removal of mask mandates is a huge blow to the disability community because it immediately puts disabled people at much higher risk of catching Covid.[i] Just as problematically, however, the government’s decision signals a lack of consideration for disabled people along with a tendency to place the burden of remaining “healthy” directly on individuals. This particularly individualized and ableist approach to the pandemic reflects a long history between individualism and ableism. Indeed, anti-maskers have used individual rights as a reason not to mask. This ableist logic has a historical legacy rooted in the history of individualism in the United States.

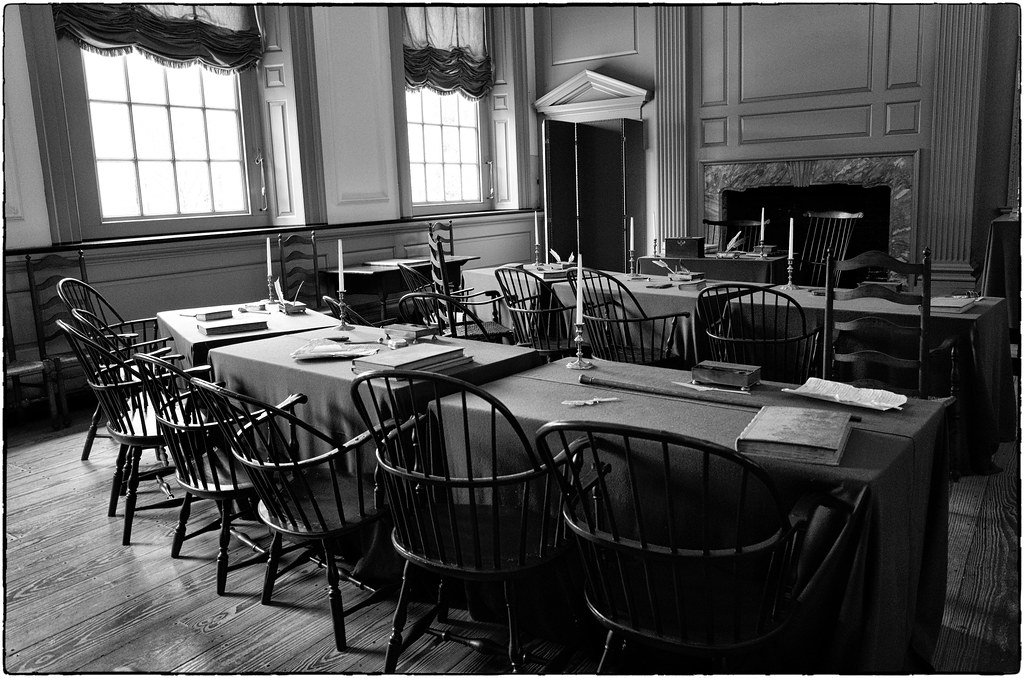

Since the founding of the United States, classical liberalism has been a central ideal of American civilization.[ii] At its core, this philosophy holds that individuals should be as free as possible from traditional or imposed obligations to others so that they can pursue self-interest. In such a world, “society” derives benefits from the successes attained by self-interest-seeking individuals. This formulation of classical liberation was most famously articulated in 1776 by Adam Smith in Wealth of Nations.[iii]

There were significant developments in the western world that paved the way for such thought. In Colonial America, the Great Awakening and the American Enlightenment contributed to a new and important emphasis on the role of the individual. The Awakening emphasized the individual’s ability to persuasively “prove” one’s “conversion experience,” and the Enlightenment venerated an individual’s capacity to employ reason to uncover natural laws and truth. [iv] By the time the American Revolutionary War had broken out, the economic individualism that Smith touted in the War’s first year, was already manifest in actual policy. For instance, in March 1776 Congress passed the Privateering Act, which allowed American citizens to legally engage in piracy against British flagged ships, keeping any spoils they obtained. In addition, in the early years of the War, Congress passed so-called “land bounty grants,” which promised land to men in exchange for enlistment in the US Army.[v]

A civilization with classical liberalism as one of its foundational pillars promotes a social environment in which ableism can flourish. This is because ensuring that the individual remain “liberated” (or at least that the viability of exercising one’s “individual freedom” seemingly persists intact) is accorded a higher societal value than addressing the needs of any one particular group. A clear historical example of this dynamic is Indian Removal. The US sanctioned the “ethnic cleansing” of Natives to ensure that poor white American men had their own individual access to land and thus personal economic upward mobility. In his 1830 Address to Congress President Jackson stated:

It gives me pleasure to announce to Congress that the benevolent policy of the Government… in relation to the removal of the Indians beyond the white settlements is approaching to a happy consummation…. It is rather a source of joy that our country affords scope where our young population may range unconstrained in body or in mind, developing the power and facilities of man in their highest perfection. These remove hundreds and almost thousands of miles at their own expense, purchase the lands they occupy, and support themselves at their new homes from the moment of their arrival. Can it be cruel in this Government when, by events which it can not control, the Indian is made discontented in his ancient home…?[vi]

Clearly, at face value classical liberalism is extremely individualistic and taken to its logical conclusion can create an opening for people to do almost whatever they please, especially when the government encourages classical liberalism. As Jackson’s words above demonstrate, laws and ethical standards could be reshaped to encourage individualistic behavior even when that behavior may harm other people.

On the other hand, in the eighteenth century, a number of measures were set in motion to ensure that there were limits to potential excess of classical liberalism. For instance, licentiousness (people’s acts of doing what they wished without considering the effects of their behavior on others) was regarded as a social vice, especially among New Divinity Calvinist ministers. The logic followed that if classical liberalism is about pursuing self-interest, then licentiousness must be a concern as one may pursue self-interest without considering the effects of behavior on others. Here, we are using the definition from early Whig thought: almost unconstrained personal liberty that could become corrosive. Later in the eighteenth century and in early nineteenth century, licentiousness’s definition changed to mainly mean sexual misconduct. This shift in meaning could mean that personal liberty came to be seen as a good thing and therefore no longer a part of licentiousness. If this is the case, then either public opinion came to outweigh these ministers, or the ministers found a way to reconcile their ideas of original sins and predestination. Indeed, Universalism, which emerged in the late eighteenth century reconciled liberalism and religion. Instead of original sin, the doctrine of Universalism claimed that humans were inherently good and therefore saved, meaning that God would resurrect them so that they could live eternally in heaven. The logic followed that if humans were inherently good, then pursuing one’s self interests could not possibly be bad, and therefore the definition of licentiousness need to change.[vii]

Universalism had other impacts beyond definitions of licentiousness. Ministers worried that, in addition to having poor morals, people would not put as much effort into self-reflection and give in to easy solutions. If your salvation does not depend on works or good deeds, then why the need for self-reflection? This “easy redemption,” to use scholar Colin Wells’s words, worried many ministers. Ministers asserted that by not subjecting one’s actions to repeated ethical scrutiny, individuals would fall into a turpitude: they would seek easy answers out of morally laden questions of public concern.[viii] This may lead them to not act in public good, which can harm society as they act only out of self-interest without regard to the wellbeing of others. Finally, there existed other ideological tenets that counter-balanced the potential excesses of liberalism. The notion, for example, of public virtue, or acting in service of the public, rather than private, good or interest, was deemed a laudable personal trait. [ix]

Constraints on classical liberalism have continuously weakened from America’s inception to the present. In part, this is due to the basic ideology of liberalism. The idea that one “is free” can stimulate questioning of established practices or inherited limits that constrain freedom, leading people to push the boundaries of socially accepted behavior.

In our current time, the world has become more individualized: people now are more disconnected than in the past as technology has allowed us to become increasingly socially isolated. This lack of connection to others has reflexively strengthened the sway of liberal ideals in our society. Likewise, the dominance that neoliberal capitalism has attained over our economy in the last fifty years has reinforced allegiance to liberalism and especially the ability to pursue one’s self-interest.

As classical liberalism has become stronger over time, modern versions of licentiousness and easy redemption have emerged with greater facility. Consider ableism in the pandemic. Ableism represents a form of licentiousness because many non-disabled individuals do as they wish (not wearing a mask or getting vaccinated) even if these actions put other people, especially disabled people who have conditions that make them high risk, in danger. Ableism also manifests as easy redemption. People live with the discomfort of masking for a while, but when they decide they no longer wish to struggle with this discomfort, they conclude that they have sacrificed sufficiently (due to having borne the inconvenience of masking) to satisfy their ethical duty to help protect public health. They seem to have somehow concluded that their previous personal sacrifice has mysteriously removed the ongoing public health need to protect disabled persons still vulnerable to Covid. In these ways, ableism illuminates concrete and identifiable excesses of classical liberalism.

Licentiousness, easy redemption, other forms of ableism and individualisms can flourish in a liberal environment because liberal societies deem the individual the most important element of said society. Due to the emphasis on the individual, classical liberalism allows ableism and other individualisms to be prioritized over the public good..

If we want to address ableism in this country, we need to consider the ideal of individualism that derives from the historical development of classical liberalism in our society. For while parts of classical liberalism make sense – such as encouraging individual initiative and protecting individual rights and liberties–, it seems that it has been taken too far, so far that it has risked the health of disabled people. Liberalism is clearly not the only factor to blame for ableism, but it is significant because it provides an ideological and social environment that can nourish ableism. When we talk about ableism, we should examine our history to see where things went wrong. The history of classical liberalism is not a bad place to start.

[i] There are several reasons that most, if not all, disabled people are at risk, not just immunocompromised individuals. One, the CDC has said many people with disabilities are more likely to get sick as they may live in congregate care; face social and health inequities and having underlying conditions (specific conditions listed here, alongside disability as risk factors). These “underlying conditions” are disabilities themselves, so the bidirectional relationship between chronic illness/risk factors and disability ensures that almost, if not all, people with disabilities are at higher risk than the general population.

[ii] Initially, the ideal of classical liberalism applied to property owning white men.

[iii] Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, Book 4, Chapter 2 (London: W. Strahan and T. Cadell, 1776).

[iv] Frank Lambert, Inventing the “Great Awakening” (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001); Robert Ferguson, The American Enlightenment, 1750-1820 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997); Michael Warner, The Letters of the Republic: Publication and the Public Sphere in Eighteenth-Century America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992).

[v] The 1788 act giving land to soldiers can be found here.

[vi] President Andrew Jackson, “Annual Address to Congress,” December 6, 1830. United States National Archives website, https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/jacksons-message-to-congress-on-indian-removal. Accessed May 19, 2022.

[vii] Colin Wells, The Devil and Doctor Dwight (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002); Ferguson, The American Enlightenment; Gordon Wood, The Creation of the American Republic, 1776-1787 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1969).

[viii] Wells, The Devil and Doctor Dwight, 15.

[ix] Ferguson, The American Enlightenment; Wood, The Creation of the American Republic; Wells, The Devil and Doctor Dwight.

Clare Tyler is an undergraduate student at the University of Rhode Island studying history and biology. Her research interests include the history of disability in 18th and early 19th century America and the history of slavery and disability. She is currently writing an honors thesis on a Black, disabled Revolutionary War veteran from Rhode Island and is a Student Fellow of the College of Arts and Sciences for summer 2022. Clare is on Twitter at @ClareTyler20.

Christian Gonzales is Associate Professor of History at the University of Rhode Island. He received his Ph.D. in Native American and Early American history from the University of California, San Diego. He was the Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in Native American Studies at Wesleyan University, and prior to arriving at URI, was Assistant Professor of History at the City University of New York, LaGuardia Community College. His recently published book, Native American Roots: Relationality and Indigenous Regeneration Under Empire, 1770-1859, explores the development of modern Indigenous identities within the settler colonial context of the early United States.