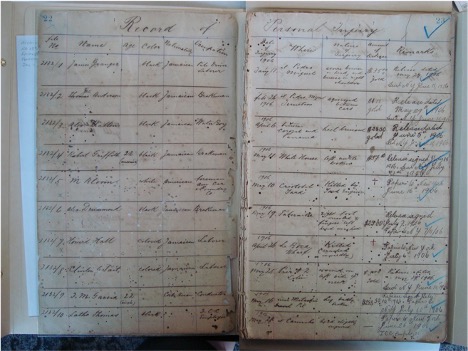

Many scholars working in disability history struggle with the violence and grief that inheres in the archives, and the burden of our responsibility to these stories. Since 2020, we have been working on a project to transcribe the injury registers that survive from the construction of the Panama Canal. These ledger books, housed at the U.S. National Archives in College Park, Maryland, document thousands of accidental injuries and deaths that occurred between about 1906 and 1914, the most intense period of the Canal’s construction.

The initial work of transcription was carried out by four student research assistants who painstakingly translated the messy handwriting and cryptic abbreviations into spreadsheets, allowing the names, occupations, and injuries to be more easily searched and analysed. We plan to move these files to a public platform once the transcription is complete in 2023.

On the surface, the injury registers are straightforward: they record names, occupations, and injuries, and sometimes where the injury occurred, what caused it, and whether the individual received any time off or compensation, among other details. But attending closely to this data reveals stories of trauma and stories of resilience, and stories somewhere in between. From our transcription work, a central tension emerged: these bureaucratic documents were reductionistic, but they could also provide a deeply humanizing perspective on the workers who sacrificed their bodies and lives to the Canal.

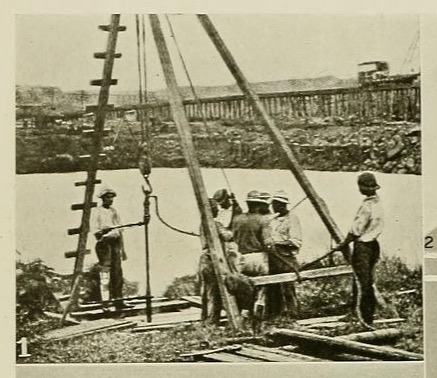

In many cases, these labourers were already on the margins of society, though not of their own communities. Some were from Europe, but the majority were Black workers from the Caribbean who were working in the Canal Zone under temporary contracts, pursuing economic opportunity while contributing to this triumphal testament to modernity and the United States’ rising global influence. They were classed as ostensibly “unskilled” labourers, relegated to crowded living conditions and the most dangerous jobs. They faced extraordinary risks from landslides, explosives, and the endless trains that carried workers into the Canal and dirt and rock out of it. “Crushed,” “mashed,” and amputated limbs are common in the records, as are hernias, bruises, and sprains. In some cases, potentially serious injuries like head or eye wounds resulted in only a day or two off work, though these may have been life-altering for the individuals who experienced them.

Though labourers might receive some compensation for their injuries, this was typically denied if the injury was deemed to be the result of the worker’s own negligence. For example, the words “own fault” appear next to the record of a labourer, documented only as O. Log, who mashed his foot while carrying a rail near Culebra, the deepest, most mountainous part of the Canal cut (January 8, 1913, Box 4). If the injury was permanently disabling, as many were, Log may have chosen to leave the Isthmus or been deported. A presidential order of May 9, 1904 had given the Canal Commission the power to exclude people from the Canal Zone and parts of Panama if their presence was believed “to create public disorder, endanger the public health or in any manner impede the prosecution of the work of opening the canal” (Letter from Roosevelt to Taft, 9). Men with chronic illnesses and disabilities would technically fall under this category. But Log may also have been transferred to a relatively sedentary job like a watchman, in lieu of compensation, or he might have moved elsewhere in Panama, eking out an uncertain living away from the Canal authorities’ reach. Did he have a family? Did anyone depend on him? Given the sketchy information about his name and background, we may never know.

The records are haunted by death and pain, but they are also records of survival一invitations to consider the creativity, community, and strength of these workers whose lives were so much bigger than entries in a register book. How do we put flesh on their bones? Are we right to try? In her work on slavery, Saidiya Hartman asks, “Is it possible to exceed or negotiate the constitutive limits of the archive?” She proposes nothing as “miraculous as … redeeming the dead, but rather laboring to paint as full a picture of the lives of the captives as possible” (11). Through close attention to the records, we might imagine, cautiously and carefully, the depth of these Canal workers’ lives, conscious always of the unknowable distance between us and them.

There are the geographies of loss and disablement, whose memory might have haunted workers’ sense of the landscapes through which they moved. A labour train collision at Bas Obispo that injured seven men in 1910 would not soon have been forgotten by the workers who passed by the site every day (August 30, 1910, Folder 1, Box 3). We know, too, that there was endless heat and humidity, noise and dirt and steam. Sometimes, tensions between men spilled over into fights, resulting in injuries: a cut hand for Robert Marson in January 1913, a bruised back for H. Brown in August (January 11, 1913 and August 15, 1913, Box 4). Perhaps they were tired and hungry, quarrelling over a bit of shade during the noon break.

Many entries left us wondering about details of workers’ personal lives, such as the presence of family or close relationships. John Alexander was listed as a “colored” man, aged 29, “with family.” In August 1906, while he was working as a sub-foreman for the Panama Railroad’s Road Department, a piece of metal entered his left calf. He received $25 in compensation for his injuries (Entry 2132/111, August 2, 1906, Folder 1, Box 1). How did his wife and children cope with this disruption to their lives? The ledger is silent. In another case, Manuel Frahar, a labourer whose nationality was listed as “native,” experienced a serious bruise to his face, as well as a dislocated ankle. A note at the end of his entry reads, “Unable to locate – Closed.” Perhaps he was owed money in compensation for his injuries, but he never received it. He may have returned to his family or friends in Panama, disappointed with his brief experience building the American canal and disappearing from its records (Entry 2132/546, July 1, 1907, Folder 1, Box 1).

Other records allow us to glimpse the lives of young people in the proximity of so much movement of dirt and machinery and humanity. One of us, for example, transcribed an entry for an eleven-year-old boy with the unusual name “Septimus.” The name and the presence of a child in the records sparked a smile, but a single word in the “Nature of Injury” column quickly changed this: “Killed.” The transcriber was struck by a sudden grief for the boy and began to wonder how many others had given him a second thought in the century or so since his death.

Septimus, who was listed as “Jamaican,” was killed in the train yard in Colon, at the Canal’s Caribbean mouth (Entry 2132/195, October 31, 1906, Folder 1, Box 1). No occupation was provided: he may have been taking a shortcut across the tracks, delivering lunch to a father or brother, or perhaps he was working informally, carrying water for the labourers, for example. As we mourn his death, we wonder who else may have mourned him.

Disability history seeks to restore the full humanity of disabled people through time; in the case of the workers on the Canal, transcribing bureaucratic records gave us a connection to these workers and their lives that was simultaneously impersonal and intimate. It was at times difficult to peer more deeply into the records, especially when the information was entered hastily and sparsely. But as historians, our job is to care for the dead (Sandle and Van Arragon 101-104). As Hartman writes, “How can narrative embody life in words and at the same time respect what we cannot know? How does one listen for the groans and cries, the undecipherable songs, the crackle of fire in the cane fields, the laments for the dead, and the shouts of victory, and then assign words to all of it?” (3). Each bureaucratic detail, approached carefully, was also an opportunity to ponder what we knew and what we did not, and to remember these workers’ struggles and sacrifices. We hope that soon other researchers and descendants, too, will be able to use these records to further the work of honouring their humanity. It is the least we can do.

Note: If you wish to inquire about family members whose names may be in these records, please email clieffers@gmail.com.

References

Folder 1 (January 11, 1906 to October 1, 1907), Box 1 (January 11, 1906 through June 18, 1908). Personal Injury Registry Books, 1906-1914, RG 185 Records of the Panama Canal, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD.

Folder 1 (January 23, 1910 to July 1, 1911), Box 3 (January 23, 1910 through October 15, 1912). Personal Injury Registry Books, 1906-1914, RG 185 Records of the Panama Canal, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD.

Box 4 (October 16, 1912 through September 30, 1913). Personal Injury Registry Books, 1906-1914, RG 185 Records of the Panama Canal, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD.

Hartman, Saidiya. “Venus in Two Acts.” Small Axe 26 (2008): 1-14.

Letter from Theodore Roosevelt to William Taft, “Letter of the President Placing the Isthmian Canal Commission Under the Supervision and Direction of the Secretary of War, and Defining the Jurisdiction and Functions of the Commission,” May 9, 1904. In Executive Orders Relating to the Isthmian Canal Commission, March 1904 to June 12, 1911, Inclusive. Washington: [Government Printing Office], 1911.

Sandle, Mark, and William Van Arragon. Re-Forming History. Eugene, Oregon: Cascade Books, 2019.

Emma Hutchinson, Jessica Samantha Craig, and Sinead O’Neill are undergraduate students at The King’s University, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. Caroline Lieffers is an Assistant Professor of History, The King’s University.