Throughout my PhD, I have been fortunate to investigate a range of topics related to the history of the Paralympics and disability sport. Within this work, I have been especially conscious of how to represent the stories and experiences of disabled athletes. Academic and ex-Paralympian Danielle Peers notes that historic representations of the Paralympics can fall into problematic stereotypes by rendering athlete as tragic figures who overcome despair via sport, and undermine ideas of athlete empowerment or resistance (Peers 2009). As I undertook a placement with the National Paralympic Heritage Trust (NPHT), in Stoke Mandeville, UK, I wanted to take this critical perspective into account. In this blog, I will briefly explore my experiences in curating content for the Paralympic Heritage Trail, outline the project and describe how the scope of the project changed to encapsulate a broader view of disability sport history. To this end, I highlight three examples of how athlete’s experiences were represented in the Trail.

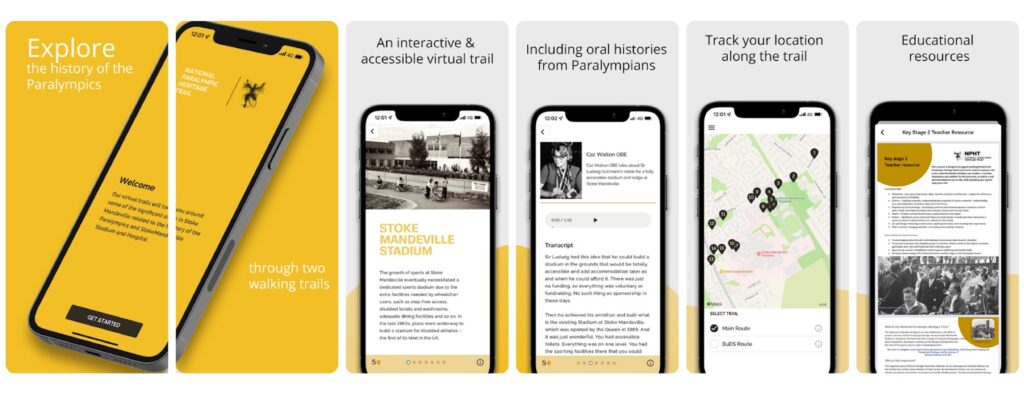

The Paralympic Heritage Trail is an app-based self-guided tour around Stoke Mandeville in Buckinghamshire, UK. Stoke Mandeville Hospital is the birthplace of organised wheelchair sport in the UK, and the ancestral home of the Paralympic movement. The precursor to the Paralympics, the Stoke Mandeville Games, was established by Sir Dr Ludwig Guttmann at Stoke Mandeville Hospital’s Spinal Injuries Centre in the late 1940s (Brittain 2012, 1-4). The trail highlights significant landmarks around the area, including:

- The National Spinal Injuries Centre (NSIC), where sport was first introduced as part rehabilitation programmes.

- Stoke Mandeville Stadium, the first of its kind in the UK and host of the 1984 Paralympic Games.

- Sites of athlete accommodation, like the purpose-built Olympic Village, or William Harding School, which was temporarily used as athlete accommodation during the 1984 Games.

The Trail project was initially designed to highlight the local history of the Paralympics, connecting landmarks and events to the international Paralympic movement. As such, the intended audience was local residents who may be unaware of the legacy of the Paralympics, or local residents who took an interest in the geographical development of the area. However, as writing for the project continued, the scope of content expanded. Now, the Trail includes a range of different historical narratives that highlighted the range of the NPHT’s archival collections – such as administrative and organisational histories, insights into fundraising for individual athletes or events, or material examples of athlete’s equipment, clothing, and medals. This allowed the app to contain a wider range of resources, such as documents and images, videos, audio clips, and 3D models of objects. Moreover, as part of the accessibility of the Trail, the app can be used remotely so those unable to physically traverse the route are able to engage with the content of the app. In turn, this broader range of content will hopefully widen the appeal of the Trail beyond those who lived in the local area.

Throughout, I wanted the perspectives and experiences of the athletes to come through in the Trail. Athletes’ experiences can be found throughout collections held by the NPHT. Examples of this presence include the donations of athletes’ memorabilia, articles written for the NSIC’s patient-led journal The Cord, or newspaper articles which highlighted mainstream recognition of athletes’ achievements. These records presented the opportunity to make human connections to the local and international aspects of the Paralympics. Nevertheless, I was cautious in how to best achieve this. In analysing two histories of the Paralympic movement, Peers criticises representations of these histories which render disabled athletes silent and invisible (Peers 2009). They explore how non-disabled scholars can reproduce concepts of disabled people as passive or tragic by emphasising the role of medical professionals and sport administrators in the history of the movement. Indeed, Peers speculates that the phrasing of ‘the Paralympic Movement’ often refers to medical experts, and not athletes. Whilst more recent scholarship concerning the Paralympics has bucked these trends, my colleagues at the NPHT and I felt it important to ensure that the perspectives and experiences of athletes were in conversation with the other historical narratives presented in the Trail app.

Athletes’ experiences were represented in a range of ways. Firstly, and most importantly, the project included a number of oral history testimonies from athletes themselves in their own words. Oral histories present opportunities to address gaps in knowledge not filled by archival materials (Abrams 2016, 16). The NPHT had already engaged with oral history methodology to highlight the experiences of athletes, and stories relating to athletes’ experiences around Stoke Mandeville helped to inform the significance of multiple stops on the route. One such story was given by John Harris, who competed in throwing events for the British Paralympic team in the 1980s and 1990s (NPHT (2), n.d.). He described his experience of accommodation at William Harding School for the 1984 Paralympics. Despite the issues with the accommodation, he fondly remembered the positive atmosphere and social experience of those Games. Memories of athletes like this were included across multiple Trail stops. Moreover, new oral histories were collected specifically for the project, to represent the experiences of athletes not present within the NPHT’s existing oral history data.

The social value of disability sport became a significant topic in the tour content, as athletes related their memories of Stoke Mandeville to friendships formed and parties attended. One stop on the trail route is in the approximate area of an old social club, located near hospital staff accommodation, where athletes and medical staff alike would socialise. The additional establishment of the Social Club Bar in the nearby Bowls Centre highlights the importance of social opportunities for athletes and patients in the area. This is reinforced by American athlete Allen Feldman’s testimony of hundreds of athletes coming together at parties and beer marquees on the evenings of competition days. I felt this topic was important to highlight on the trail, due to the social potency of sport. While conducting oral history interviews for my PhD dissertation on the history of wheelchair sport technology, I found that wheelchair sport was initially introduced as a form of physical rehabilitation, but athletes and practitioners quickly noted the social and psychological benefits of sport, as it encouraged social interaction, competitiveness, and camaraderie between patients. The physical and social appeal of wheelchair sport encouraged patients to continue engaging with these activities beyond the rehabilitation ward. Athletes established disability sport events and clubs, which were important sites of community and support for many disabled people. Accordingly, it was important for the Trail to capture this aspect of disability sport history.

Finally, I connected athletes’ stories to their wider lives and contemporary attitudes towards disability. This is achieved at a stop besides a road sign for Gwendoline Buck Drive. The street is named after Gwen Buck, a British Paralympian who won 10 medals across different disability sport events between 1960 and 1976, including table tennis, lawn bowls and swimming. (NPHT (1), n.d.). The WheelPower collection contains a range of information about Gwen Buck, such as newspaper articles about her sporting achievements, medals from different Paralympic and Commonwealth Games, and her trophy for winning Disabled Sports Personality of the Year in 1973 from the Sports Writers’ Association. Alongside recognition of her sporting prowess, other details of her life can also be found. One such item is a newspaper article about her engagement to fellow wheelchair user and Paralympian John Buck. The article, titled “Wheelchair-girl finds Romance,” was published in the early 1950s, features language around the pair ‘overcoming their disabilities to lead normal lives’. Gwen and John’s romance is framed via their status as disabled people, as the article begins: “They hugged each other despite the chromium wheelchairs that almost kept them apart.” This sentence could be interpreted simply as reference to the bulky wheelchairs provided to wheelchair users by the National Health Service in the mid-twentieth century (Woods and Watson 2004). However, the implication of the author appears to be that disability usually restricted any hope of romance or ‘normality.’ Gwen and John bucked this trend.

Overall, the items in the collection show their life together, including their wedding photos and photos of the pair at social events at Stoke Mandeville. I chose to include these aspects of Gwen and John’s lives as I felt it added an important personal touch to the wider narrative of Paralympic history. New approaches to rehabilitation which utilised sport led to modern elite disability sport in the Paralympics, but also facilitated independent living, employment, and companionship. These stories are as much part of Paralympic history as medical techniques or athletic achievements.

My experiences of curating content for the Paralympic Heritage Trail ultimately broadened my understanding of disability sport history. As I considered how to represent athletes’ experiences in the Trail format and in the narratives I constructed, I gained a deeper appreciation for Peers’ critique of Paralympic histories. By aiming to link human stories to instances of local, medical or sporting history, my hope is that the Trail project avoids these errors.

The Paralympic Heritage Trail app is set to launch later in 2023, available on iOS and Android devices.

References

Peers, Danielle. 2009. “(Dis)Empowering Paralympic Histories: Absent Athletes and Disabling Discourses.” Disability & Society 24, no. 5 (August): 653–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590903011113.

Brittain, Ian. 2012. From Stoke Mandeville to Stratford: A History of the Summer Paralympic Games. Champaign, Illinois: Common Ground Publishing.

Abrams, Lynn. 2016. Oral History Theory, 2nd ed. London: Taylor & Francis.

National Paralympic Heritage Trust (NPHT) (1) . n.d. “Gwen Buck.” Accessed April 22, 2023. https://www.paralympicheritage.org.uk/gwen-buck.

National Paralympic Heritage Trust (NPHT) (2). n.d. “John Harris.” Accessed April 22, 2023. https://www.paralympicheritage.org.uk/john-harris.

Woods, Brian, and Nick Watson. 2004. “In Pursuit of Standardization: The British Ministry of Health’s Model 8F Wheelchair, 1948-1962.” Technology and Culture 45, no. 3: 540–568.

Samuel Brady is a PhD researcher at the University of Glasgow and the National Paralympic Heritage Trust, exploring the social, political and technological history of sporting wheelchairs. Alongside his research interests in disability, technology and sport, he is also interested in the intersections between race/ethnicity and disability, primarily concerning Jewish history and studies. Samuel is also a co-founder of the UK Disability History and Heritage Hub.